Webmaster’s Note: We are pleased to reprint this important historical study of gem prices from Sydney H. Ball (1877–1949). This is one of the few scholarly studies of gem prices in existence and we are sure you will find it fascinating. Reprinted from Economic Geology, August, 1935, Vol. 30, No. 5, pp. 630–642.

“That which is beautiful is never too costly, nor can anyone pay too little for that which gives pleasure to all,” said Abu Inan Farés, Sultan of Morocco, on completion of a beautiful building at Fez. To emphasize his delight, he refused to look at the architect’s bill, but tore it up and threw the fragments into the River Fez.

Since about 100,000 B.C., man has prized and has desired to possess beautiful stones, and almost from that date he began to offer a rabbit for a bit of chalcedony or a worked flint for a quartz crystal. The earliest gem price known to me, however, dates only from the 4th century before Christ. The musician, Ismenias, purse-proud and ostentatious, heard of an emerald engraved with the figure of the nymph Amymone, obtainable in Cyprus for six gold staters (about $30.65). He sent an agent to purchase the gem, and by shrewd bargaining the latter, returned with it and two of the six staters. Ismenias, with typical musician’s temperament, flew into a passion, crying that the agent had ill-treated him by his bargaining and by thus impairing the merit of the stone. Unfortunately, neither is the weight of the stone known, nor the relative value of the material and the engraving. Theophrastus, who lived from 372–287 B.C., states that the carbuncle, in which designation, doubtless, both our garnet and ruby and perhaps our spinel are included, “is extremely valuable, one of a very small size being prized at forty aurei” (about $180). The earliest satisfactory gem prices are those of the Arabian mineralogist, Teifaschi, who in 1150 A.D. ranked the gems as follows: emerald, diamond, ruby and sapphire. He recognized the essential fundamentals of modern gem valuation.

He sent an agent to purchase the gem, and by shrewd bargaining the latter, returned with it and two of the six staters. Ismenias, with typical musician’s temperament, flew into a passion, crying that the agent had ill-treated him by his bargaining and by thus impairing the merit of the stone.

With the exception of radium and a few other very rare elements, the finer precious stones, the diamond, emerald, ruby and sapphire, are the most valuable of all commodities, and their value is concentrated in small weight and bulk. One could conceal a pound of such gems, worth, say, $10,000,000 around his person, and a porter could pack the equivalent of $2,000,00,000 worth of fine gems, except for the fact that such an amount of fine gems could not be procured.

This is a study of the prices of emeralds, rubies and sapphires during the past, and more particularly the last 150 years; it supplements the study of diamond prices made by the writer [1] seven years ago. Deeply colored red, green and blue diamonds, although the most expensive of gems, arc not considered here, since they are so rare.

The emerald was known to the Egyptians as early as 2000 B.C.: the sapphire and ruby were first known in Europe to the Etruscans and Greeks between 600 and 480 B.C. The latter gems and the diamond were, however, doubtless known to the Hindoos about 800 B.C. [2]

The value of a precious stone is determined by three main natural characteristics, its beauty (either fire or brilliancy or color), its durability, and its rarity; and a fourth artificial one, the perfection of its cutting, or in the trade, its “make.” Minor factors are an adequate supply, its portability, its international market, tariffs, and world economic conditions. These are the factors that determine the value of a fine diamond, ruby, emerald, or sapphire, and in a broad way have made them the most precious of human possessions at least, from the days of Pliny to our own time, a period of some 1900 years. The demand for them is relatively steady and sales are governed by the purchasing power of the world. Fashion, superstition, royal sponsorship, fear of substitution of imitations, nationalistic pride, and effective publicity more specifically affect the less valuable gems.

Durability is a factor common to the four precious stones here, considered, but of course to a higher degree in the diamond than in the sister gems, ruby and sapphire, and to a vastly higher degree than in the emerald. The relative softness of the olivine, or peridot, causing it to become scratched if worn in a ring, is one of the factors which lost the gem its former vogue. A diamond, a ruby, or a sapphire is as nearly indestructible as anything in this changing world: time scarcely affects it and fire damages it little. It is probable that an American of today wears a gem that once graced Charlemagne’s court, and scores of Greek and Roman engraved gems still exist.

With the exception of radium and a few other very rare elements, the finer precious stones, the diamond, emerald, ruby and sapphire, are the most valuable of all commodities, and their value is concentrated in small weight and bulk.

Were gems common, they would lose much of their value. I believe, however, that gem owners can face the future complacently: while the unmined supply of diamonds is doubtless adequate, the fields which in the past have supplied us with the best rubies and emeralds are now abandoned or worked only on a very small scale, and the yearly increment to the world’s sapphire supply is not large. But more than 200 years after the conquest of Peru, an over-abundant supply ruined the emerald market. Father Joseph de Acosta tells us that when he returned from: America in 1587 there were on his ship “two chests of emeralds; every one weighing at the least foure arrobas” (i.e. a total of 200 pounds). To show the effect on the price, he states that soon after the conquest a Spaniard in Italy showed a jeweler an emerald…

“…of an excellent lustre and forme: he prized it at a hundred ducats: he then shewed him another greater than it, which he valued at 300 ducats. The Spaniard drunke with this discourse carried him to his lodging, shewing him a casket full. The Italian seeing so great a number of emeralds, sayde unto him,‘Sir, these are well worth a crowne a peece.’”

Overproduction has been even more disastrous in the case of a number of semi-precious stones. The enchanting cat’s-eye shared its popularity with its meaner sister, the tiger’s-eye, which latter was highly esteemed from 1880 to 1890, particularly ill America. Tiger’s eye once sold for $6 a carat or even more (say $11,200 a pound), but unfortunately it occurred in quantity on the Orange River, South Africa. Two speculators, each simultaneously, sent a whole cargo from this locality to London, and the price immediately fell to twenty-five cents a pound. In 1652, a fine amethyst is said to have been as valuable as a diamond, and a relatively high price was maintained until Civil War times, when large imports from Brazil rendered the stone comparatively valueless.

At present the greatest “mine” of gems is that in the hands of the wealthy. Unlike secondary copper, “secondary” gems only return to the market following a complete economic upheaval. The Russians of wealth were Oriental in their love of gems and their shrines were heavy with precious stones. After the revolution, these reached the European and American markets, in part through sales by needy refugees but largely through shipments by the Bolshevik government. It is a tribute to the stability of the gem market that the vast quantities of Russian gems thrown upon it from 1918 to the present time have been absorbed. To heighten the effect, this period coincided with that in which, due to the World War, many European nobles and some kings were forced to dispose of jewels which had been family heirlooms for generations. In normal times, this “mine” is a price stabilizer, for although through financial reverses or death of owners it disgorges a few gems every year, the amount is increased if gem prices become tantalizingly high. While an oversupply of gems is detrimental to the price, an undersupply may also be undesirable. About fifty years ago, the supply of good emeralds was so inadequate that jewel shops frequently displayed few or none, and people turned to other stones more familiar to them. We, who are interested in the diamond, are satisfied that the adequate supply of that gem, guaranteed by large, efficient mining companies, is one factor accounting for its increasing popularity during the past half century.

At present the greatest “mine” of gems is that in the hands of the wealthy. Unlike secondary copper, “secondary” gems only return to the market following a complete economic upheaval.

Political refugees throughout the ages have found the portability of gems valuable, as did that remarkable traveller and business man of 650 years ago, Marco Polo. When he and his uncle returned to Venice in 1295, their relatives failed to recognize these men garbed in shabby Tartar clothes and almost unable, through long disuse, to speak their native tongue. So the Polos invited their relatives to a stately banquet, and after each course they changed their garments of costly fabrics, the cloth of which was immediately cut and divided among the servants. When the banquet was completed and the servants had retired, Messere Marco brought from a chamber the three travel-stained coats in which the travellers had returned to Venice. With sharp knives, the seams were ripped open and from them came many large rubies, sapphires, garnets, diamonds, and emeralds so artfully concealed as to avert suspicion even if attacked by robbers. Upon quitting the service of the Great Khan of China, they had exchanged their gold for the most precious of gems, allowing that such a quantity of gold could not be transported over a road so long and so difficult. And Gian Battista Ramusio ends the tale with the naïve statement that the relatives “now saw that in spite of all their former doubts, these were really the honored and worthy gentlemen of the Polo family as they had claimed to be, and they therefore paid them the greatest honor and reverence. And when the story became current in Venice, straightway the whole city, gentle and simple, flocked to the house to embrace them, and to make much of them, with every conceivable demonstration of affection and respect.”

The prices of precious stones are, and have been for well over 500 years, standardized throughout the civilized world, due to a universal demand for them and to their portability. Vasco da Gama returned to Portugal from his first trip to India in 1499 with few jewels, since he found pearls and jewels very dear there. Somewhat less than two hundred years later, Tavernier states that prices of all fine gems except the diamond, and at times the emerald, are higher in India than in Europe and that most gems should be brought from Europe to India by traders and not purchased there. About 75 years ago even the diamond ceased to be an exception, and today one must be a knowing gem expert to advantageously purchase precious stones in the East. The Eastern potentates to this day are frequent buyers of especially fine gems in competition with the rich of Europe and America. In 1859, while Brazil was still the premier diamond producer of the world, diamonds, according to supply, might well be cheaper in London or Paris than in Rio de Janeiro.

In this day of intensified artificial restrictions to world trade, gem values are affected by duties; one of the recent depressants on the American prices of gems, largely the basis of the curves herewith presented (Fig. 2), was the reduction in July, 1930, of the American duty on cut gems from 20 to 10 per cent. ad valorem.

Vasco da Gama returned to Portugal from his first trip to India in 1499 with few jewels, since he found pearls and jewels very dear there. Somewhat less than two hundred years later, Tavernier states that prices of all fine gems except the diamond, and at times the emerald, are higher in India than in Europe and that most gems should be brought from Europe to India by traders and not purchased there.

Naturally, the world price of gems is affected unfavorably by financial panics and major wars. The French in the latter half of the 18th century bought gems to an extravagant degree, and those of the upper classes who were lucky enough to escape from the horrors of the French Revolution found their gems a means of subsistence in their new homes: denuded as was the homeland of diamonds and pearls, the social leaders after the Revolution were forced to be content with cameos and other inexpensive stones. As the United States is the largest purchaser of gems today, its prosperity in the years immediately before 1930, and its lack of excess funds from that date to this, are expressed in the price curves of the principal gems, although the present trend seems stationary and should soon be upward.

The notable increase in per capita wealth during the past fifty years multiplied the number of potential gem buyers. With the consequent increase in the number of wealthy individuals, the demand for large gems has broadened, and in the past two decades has perhaps tended to force down relatively the price of one-carat stones, the unit used in the table, since such stones have been supplanted by larger gems in the finest jewelry.

Fashion is a minor price factor among the finer gems, since they are almost always in fashion. From about 1916 to 1922, however, the ruby was less sought after than normally. On the other hand, the emerald was exceedingly popular in France when Napoleon III was emperor, green being the imperial color. Many of the minor gems, the garnet, amethyst, olivine, and topaz, are, however, much less popular than formerly. Some of us may have forgotten that in the nineties, no American dandy was well groomed without his cat’s-eye.

Superstition plays its part in gem values; for example, the senseless prejudice still held by otherwise sensible people against the glorious opal. In India, flawed or off-color sapphires are considered unlucky, although fine sapphires bring good luck.

Gems have always been considered appropriate votive offerings, and the famous shrines of the Roman Catholic, Greek Catholic, Buddhist and Brahminic faiths in particular are treasure-houses of beautiful gems. The emerald is in considerable demand for ecclesiastical use, as the stone is supposed to symbolize faith; green being one of the liturgical colors, the gem is used on altars and in vestments. The sapphire in the Middle Ages was supposed to cool all human passions, hence its frequent use in bishops’ rings.

Superstition plays its part in gem values; for example, the senseless prejudice still held by otherwise sensible people against the glorious opal. In India, flawed or off-color sapphires are considered unlucky, although fine sapphires bring good luck.

Royal sponsorship has had its effect on gem prices. Frederick the Great of Prussia was a great admirer of chrysoprase, perhaps because it was mined in territory captured by him in 1745 in the Second Silesian war. His patronage for a time notably increased the prestige of this attractive species of quartz. The stone selected by members of the British royal family to be set in the bride’s engagement ring has always gained in popularity, more particularly in the British Empire. We may cite the cat’s-eye given Princess Louise of Prussia by the Duke of Connaught (1879); the emerald engagement ring of Viscount Lascelles and Princess Mary (1922); and the sapphire rings of the Duke and Duchess of York; (1923) and of the Duke of Kent and Princess Marina (1934).

From the time of the Egyptians, gems have been imitated, but few false gems are perplexing to any but the tyro. In 1890, however, Fremy and Verneuil succeeded in producing synthetic rubies and sapphires, and synthetic rubies began to appear on the market in 1904–5, and sapphires in 1909–10. For a time, the prices of these gems were unsettled; but when it was established, about 1912, that the short-comings of the man-made material could readily be detected by any competent jeweler, the prices of rubies and sapphires continued on their upward course.

Nationalistic sentiment may cause a rare precious stone to be abnormally popular in the land of its origin; the outstanding case was that of alexandrite in Czarist Russia; in America also the local gems, benitoite, kunzite, hiddenite and tourmaline are more commonly used than elsewhere. Alexandrite was first found in the Urals on the day the Czarevitch, Alexander Nicolajevitch, later Alexander II, became of age. This was enough to render it popular in Russia, but the stone, green by natural, and red by artificial light, combined the colors of the Imperial Guard.

Effective publicity increased the value of gems in the Middle Ages, for in those days the trade was accustomed to exaggerate the perils of obtaining precious stones from the Eastern gem fields: with transportation such as it then was, the perils were enough without multiplying the number of man-eating tigers that waylaid the traveler, Without transforming peaceful natives into cannibals, and without introducing a fancy assortment of dragons, gryphons and monstrous serpents. The first tourmaline recognized in Europe was found in 1703 among a package of Ceylonese stones discarded by a Dutch lapidary. The children of the neighborhood were intrigued by the gem’s ability to attract light objects, and dubbed it “aschentrecker” or “ash drawer.” French and English scientific circles started furious discussion of this phenomenon, and the socially prominent eagerly sought a piece of tourmaline jewelry. One of Hogarth’s paintings shows a gay youth of the day absorbed with the wonders of his tourmaline as he held it in the rays of the sun.

The world has been relatively consistent in its ranking, of gems for some 1900 years, for Pliny informs us that after the diamond, “the most costly of human possessions” known “to kings only and to very few of them,” the Romans ranked the pearl, then the emerald, and then the opal. He does not give a rating of the ruby and the sapphire. The Five Great Gems of the Hindoos (Maharatnani) from time immemorial have been the diamond, pearl, ruby, emerald and sapphire. In the 13th century, the Persians ranked the diamond after the pearl, ruby, emerald and chrysolite. But the primitive cutting of that day brought out but a small fraction of the diamond’s brilliancy and fire.

|

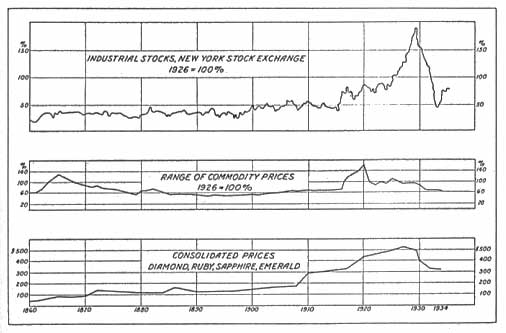

| Fig. 1. Graph showing price range of diamond, ruby, sapphire and emerald in comparison with industrial stocks and commodity prices, 1860 to 1934. |

Figure 1 gives an average for the past seventy-four years of the price graphs of the diamond, emerald, ruby and sapphire without weighing [3] the relative sales volume of the four gems. I have added thereto a curve representing the mean price of representative industrial stocks quoted on the New York Stock exchange, and likewise a commodity price curve. The upward tendency of the gem prices, together with their relative stability, correlates the findings of Mr. Lewisohn, a writer in the French Magazine “Vu.” A listing of the richest men of the world before and after the 1929 panic showed him that the Indian rajahs whose wealth was largely in gold and precious stones had fared much better than American and European multi-millionaires with their wealth in stocks and bonds: This is not, however, set forth as an argument for the investment value of gems, which pay no dividends except those of the constant enjoyment of beauty. Further, it should be emphasized that a forced sale of gems in times of financial distress might net but 50 to- 70 per cent. of the price at which they were bought, although if given ample time, the jewel broker should be able to dispose of gems at prices approximating, those given in Figure 2.

|

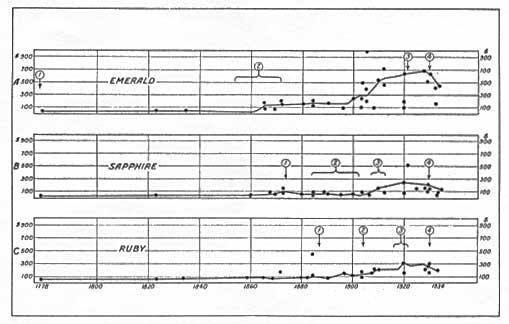

Fig. 2. Prices of precious stones, I778–1934. Emerald:–(1) 1567–1800. Market depressed by oversupply of Colombian emeralds. (2) 1852–1871. Very popular under Third Empire (France). (3) Princess Mary’s engagement ring-stone, emerald. (4) 1930. American tariff reduced from 20 to 10 per cent ad valorem, emphasizing effect of depression. Sapphire:–(1) 1871–2. After Franco-Prussian War, became very popular. (2) 1883–1903. Four new fields increase supply greatly. (3) 1909–1910. Synthetic sapphires appear on market; by 1912 adverse effect ended. (4) 1930. American tariff reduced from 20 to 10 per cent. ad valorem, emphasizing effect of depression. Ruby:–(1) 1887. Burma Ruby Mines Ltd. starts operations. (2) 1904–5. Synthetic rubies appear on market. (3) 1916-22. Ruby temporarily out of vogue. (4) American tariff reduced from 20 to 10 per cent. ad valorem, emphasizing effect of depression. |

The prices used in compiling the graphs are to be considered as approximations only of the value of a good one-carat cut stone. In the first place, the authorities depended upon do not in all cases specify the grade of gem priced; and further, in colored gems there is a wide latitude in what two experts consider a fine stone. In a broad way, however, the graphs are believed to present a true picture of changes in gem prices. While a number of early gem prices exist, covering the period from the 12th to the 18th centuries, they are few, and probably refer to stones of such varying grade that it would be of doubtful value to extend the diagram to include them.

From about 26 A.D. to about 1500 A.D., a one-carat white diamond was the most expensive stone; from 1501 to about 1800 the ruby led; from 1801 until 1872 the diamond regained and held the lead, but from the later date to the present day the emerald has been the most expensive stone.

Exceptionally fine gems are so rare that they have no fixed price, and each transaction becomes a matter of negotiation between buyer and seller. As with a fine painting or other work of art, set rules do not hold. Such are red, green, or blue diamonds, white diamonds of unusual size and brilliancy, rubies of over four carats, emeralds of fine deep color and relatively free of flaws, particularly if of good size, and unusually fine sapphires.

Exceptionally fine gems are so rare that they have no fixed price, and each transaction becomes a matter of negotiation between buyer and seller. As with a fine painting or other work of art, set rules do not hold.

The ruby (Fig. 2, C) has always been one of the highest priced gems, alternating with the diamond and the emerald for the leadership in one-carat prices, while exceptionally large rubies (3 to 9 carats or more), due to their great rarity, are the most expensive of stones. Such stones bring from $3000 to $7000 a carat. About 1592, Linschoten introduced a rule for the valuation of gems, namely, the value of a stone of more than one-carat is the product of the value of a one-carat stone by the square of the stone’s weight. For the past sixty years, this rule has been valueless in diamond valuation, clue to the extraordinary number of large stones reaching the market from South Africa. It is still approximately correct in ruby valuation, the resulting price being too high in the case of stones only slightly over a carat and too low in those of three carats or more. Benevenuto Cellini, in 1558, gave the following figures for a one carat stone:

- Ruby

$779.20

$779.20 - Emerald

389.60

389.60 - Diamond

48.70

48.70 - Sapphire

4.87

4.87

I infer that the ruby and emerald were exceptionally fine stones, or perhaps Benevenuto, as he sometimes did, was exaggerating a bit. The one-carat ruby continued to be more valuable than the diamond up to the end of the 18th century, but the diamond then passed it and continued higher in price until 1884, when for five years the ruby exceeded it. About 1872 the price of a fine one-carat emerald passed that of both diamond and ruby, and presumably the emerald will in the future retain first place. In gems of two carats or more, however, even in the first eight decades of the 19th century, rubies were more valuable than diamonds. From about 1906 to 1908, the price was slightly depressed by the appearance on the market of synthetic rubies, while from about I906 to 1922 the stone somewhat lost its vogue. Since the company producing fine rubies, Burma Ruby Mines Ltd., is no longer operating, further advances are likely.

About 1592, Linschoten introduced a rule for the valuation of gems, namely, the value of a stone of more than one-carat is the product of the value of a one-carat stone by the square of the stone’s weight. For the past sixty years, this rule has been valueless in diamond valuation, clue to the extraordinary number of large stones reaching the market from South Africa.

The price of the sapphire (Fig. 2, B) is much below that of the diamond, but Streeter, in 1884, reported that some fine 2 to 3 carat stones were then as valuable as diamonds of the same weight. In the interval from 1880 to 1905, the price decreased due to the bringing into production of four important fields within a period of but twelve years, namely: (I) the beginning of sapphire mining in Queensland in 1881 (discovery 1876, important production not until 1891); (2) the discovery of the Kashmir field in 1882 and (3) that of Phailin, Cambodia, in 1885; and (4) the opening up of the Montana field in 1893 (sapphires first recognized there in 1865). Fine large sapphires are by no means as rare as fine large rubies or emeralds, and in consequence the price increase per carat is by no means as great as in those gems: a ten-carat stone might be worth from 40 to 60 times the value of a one-carat stone.

The emerald (Fig. 2, A) is at present the most precious of all gems; it has always held a high place except from about 1565 to 1790, when the price was depressed by unwieldy exports from South America. The value of an emerald is determined by depth of color, brilliancy and relative freedom from flaws, for flawless emeralds are practically non-existent. Stones of good quality over one-carat, more or less, increase in value by the square of the weight–a generalization true since the 16th century.

Sydney H. Ball

26 Beaver Street,

New York City,

March 1, 1935

![]()

Footnotes

1. The Jewelers’ Circular, vol. 94, July 27, 1927, pp. 31–35; Eng. And Min. Jour., Aug. 6, 1927. (back to text)

2. Ball, Sydney H.: Historical Notes on Gem Mining. Economic Geology, vol. 26, pp. 681–738, 1931. (back to text)

3. Diamonds sales much exceed those of all other gems combined; accounting as they do for perhaps 95 per cent. of the total. (back to text)