With Pala Presents, we offer selections from the library of Pala International’s Bill Larson, who shares with us some of the wealth of information in the realm of gems and gemology. The following three articles, from 1893 to 1948, look at California gemstones in general and rubellite/lepidolite in particular. (Color images are from the lightbox of Pala International.)

- “Notes on the Occurrence of Rubellite and Lepidolite in Southern California” by Harold W. Fairbanks, Berkeley, Cal., from Science

- “Precious and Semi-Precious Stones of California” by Alice M. Keatinge, from Overland Monthly

- “The Gem Deposits of Southern California” by Richard H. Jahns, from Engineering and Science Monthly

|

Notes on the Occurrence of Rubellite and Lepidolite in Southern California

By Harold W. Fairbanks, Berkeley, Cal.

An article originally published in Science, Vol. XXI, No. 520, January 20, 1893, pp. 35–36

THE work of the California State Mining Bureau has recently brought into notice a very interesting association of minerals in San Diego County, California. The most important of these are lepidolite and rubellite. The former remarkable for the great quantity and purity in which it occurs, and the latter for its exquisitely radiated crystal aggregates. The ruby-tinted tourmaline imbedded in the pale lilac-colored mica presents a picture of beauty rarely equaled in the mineral kingdom. Before giving a detailed description of the occurrence of these minerals, a few words on the general geology of the district may not be out of place.

San Diego, the southern county of the State, is dominated by one main system of mountains known as the Peninsula Range. This consists of a confused mass of mountains and valleys rising gradually from the coast to the summit, forty miles inland, from which the descent is quite abrupt to the Colorado Desert. The average height of the watershed is about four thousand feet, but toward the northern boundary of the county, Mount San Jacinto reaches an altitude of about ten thousand feet. This Peninsula Range consists chiefly of granite which often takes on a dioritic facies. Dark basic diorite and rocks of the norite type occur as intrusions of considerable magnitude. Quartzite, mica schist, and thin bedded gneisses form long, narrow areas extending a little west of north and east of south. They represent extremely metamorphosed remnants of the original sedimentary formation.

Lying on tile west of the summit of the range and extending parallel with it is a strip of granitic country filled with irregular dikes or veins of coarsely crystallized quartz, feldspar and muscovite; or frequently of feldspar and quartz only, in the latter case taking on a pegmatitic structure. Black tourmaline in irregular crystals is generally characteristic of these dikes.

|

| From the Himalaya Mine. A matched pair of rubellite rounds, 8.68 tcw. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

The rubellite and lepidolite are found associated with an immense dike of this character near Pala, a short distance west of the foot of Smith’s Mountain. The dike occurs in one of the norite bosses which forms a high hill over half a mile across. Similar bodies of pegmatitic rock are found in the granite in the vicinity but contain no rubellite. The outcrop is tracible along the eastern slope of the hill for nearly three thousand feet, in places forming a precipitous ledge. It gradually increases in width toward the southern end, where it is three hundred feet across.

It is near one edge of this great mass of pegmatite, and inclosed in it, that the minerals in question occur.

The northern portion of the dike contains no tourmaline; the dominant character being that of a very coarse muscovite granite, with a sprinkling of minute garnets. Both large and small bodies of finely formed pegmatite lie apparently wholly isolated in the coarse granite.

As the dike is followed southward to a point about midway in its course, crystals of black tourmaline begin to appear in abundance. One crystal ten inches long appeared broken into a dozen pieces, which had been moved a slight distance apart but were perfectly angular. The quartz-feldspar matrix showed no signs of crushing, and it is difficult to understand how the appearance could have been produced unless the crystal existed prior to the consolidation of the yielding magma.

Parallelism of the smaller and more slender crystals is often to be observed as taking place about the larger ones. Green tourmaline is present in small amount. It does not generally show any crystalline form, but is disseminated in small granular particles irregularly or aggregated about the black tourmaline.

The lepidolite appears here first in small irregular patches. A few yards to the south it forms a well-defined vein, and is filled with minute needle-like crystals of rubellite. Quartz crystals with fairly well defined boundaries are scattered through it.

|

| From Pala, California. Two pink tourmalines. Left, 2.49 ct; right, 2.16 ct. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

At the point where the lepidolite reaches its greatest width, about sixty feet, it contains very little rubellite and is quite massive and pure save for granular aggregates of an acid plagioclase feldspar, probably oligoclase. It is near the southern end of this great body of lithia mica that the rubellite appears in the large radiated aggregates. Fan-shaped clusters of rubellite also occur in the quartz and feldspar adjoining the lepidolite. Single crystals in these groups are often fifteen inches long and one-half inch in diameter. One cavity containing good quartz crystals has been found, and it is possible that with farther exploration gem tourmalines may he found. Many of the smaller crystals in the lepidolite are clear and of good color, but are full of checks.

The rubellite crystals are generally gathered in radial aggregates six inches to a foot in diameter, but sometimes occur singly. Single crystals appear with smaller ones branching from one end presenting a tree-like form, or two or more intersect each other so as to form a cross. The aggregates are sometimes slender, with a slightly wavy course. The crystals either branch outward without any order or they all incline one way, giving the appearance of a fern. In other specimens lines of crystallization radiate from a common centre; curved or club-shaped crystals branching from each line. Hematite is sometimes found coating the tourmaline crystals.

|

| From the Himalaya Mine. A sphere weighing 153.57 carats and measuring 26 mm. From the early 20th century. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

Nine minerals are thus found associated together here—quartz, feldspar, muscovite, garnet, hematite, oligoclase, [and] green, red, and black tourmaline.

A somewhat similar occurrence of minerals is reported from the mountains of Lower California, but nothing is known about it. The granitic portions of the Sierra Nevada and Peninsula Ranges contain but few rare or beautiful minerals, and on that account the deposit at Pala is all the more remarkable.

|

Precious and Semi-Precious

Stones of California

By Alice M. Keatinge

An article originally published in Overland Monthly, Vol. LXXI, No. 1, January 1918, pp. 53–56

THE gold mines of California have become famous in history, but little is known outside of scientific circles, even to many of the residents of the State, of the comparatively late discovery of precious and semi-precious stones in the southern part of California—such an assemblage in variety and quality as the world has never before seen. These gems are bought up by Tiffany & Co. and other New York firms direct from the mines, and are better known in New York, Paris, Spain, Russia, Germany and China than in California. The most important of the gem mines are in San Diego, Riverside, San Bernardino and Los Angeles Counties. They were discovered only a few years ago, but the mines have yielded great quantities of rich mineral. Many of the gems were strange to the prospectors, who were searching for other minerals. The first tourmaline was discovered by a prospector who was looking for gold. A red reflection or light, shining through an aperture in the rocks, attracted his attention, and, striking his pick into the ledge, he uncovered seven great bars of tourmaline. He took them to a local jeweler, and directed him to saw it open. But the jeweler’s saw was not strong enough, so after vain attempts to ascertain what the mineral was, he went to New York and sought the wisdom of a lapidary, who told him that it was a nice specimen, but otherwise of no value, and that it was a pity to mar it with the saw. The lapidary offered him a hundred dollars for the specimen. The man refused to sell and insisted that the lapidary should saw it open. It was then found to be packed with pencils of tourmaline banded in beautiful colors of red, green, blue and white. He sold it for $2,500. The bar was three inches wide by seven long.

Many new gems, strangers to mineralogists and lapidaries, are being found. The most valuable one is the gem kunzite, named for Dr. G. F. Kunz (Tiffany’s expert on gems), who was the first to decide on the rank and value of the gem. In value and beauty it closely follows the diamond. Its color ranges from white to pink lilac and dark lilac.

|

| From Pala, California. A nice pair of large kunzites, 79.28 tcw, 21.55 x 15.28 x 14.92 mm. Inventory #19903. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

Dr. Kunz, who is an expert and student of precious stones, declares that California is now to see a gem age, the most famous and richest of her eras. She has had her gold harvest, her luxurient agricultural productions from field, orchard and gardens, and now comes the discovery of her wealth of sparkling gems.

Fifteen counties have furnished specimens of diamonds, some of good size, but most of them small, though of good quality. These, as a rule, come from placer sands. Garnets of excellent color and brilliancy, are found in the placer sands of almost every county in the State. The miners call them “California rubies.” On the Reed ranch (the station for which is Reed’s), near Tiburon, are found garnets of a fine quality and beautiful color and luster. They are imbedded in the rocks scattered over the hills opposite San Quentin. The distance, from San Francisco, is but half an hour by boat and train. It is a charming spot in spring time, with the early flowers for company, and the waters of the bay just a little way off sweeping the shores of the field.

There are many varieties of the copper formations of semi-precious stones, malachite, azurite and chrysocolla; besides these are lapis lazuli, chrysoprase and californiate. The latter is a gem-mineral recently discovered, resembling jade in color and quality. Quantities of the mineral are shipped to China for use instead of jade.

Jasper is common in many localities. A fine quality in shades of green and yellow occurs at Murphy’s, Calaveras County. Red and green jaspers of a coarser texture are used for paving the streets of San Francisco. These red and green jaspers may also be seen on any of the Marin County roads that have lately been graveled. Agate, chalcedony, jasper and rock-crystal pebbles are found on the rock-strewn beaches of California. On the sands of almost any of the protected beaches a few of these pebbles will reward the seeker. They are of various colors, golden-yellow, blueish-gray, pink-green, white and some as transparent as moonstones, but lacking the play of light which the latter display. Pescadero, near San Francisco, in San Mateo County, has a greater variety and better pebbles than any of the beaches in the State.

On the shores of Lake Tahoe are pebble beaches well known to the visitors and residents of the locality. Redonda [sic], near Los Angeles, has an important pebble beach, and Catalina Island’s moonstone beach is a favorite resort of tourists. The latter has another beach covered with large rocks and coarse pebbles, called sardonyx. These stones are beautiful when polished, and unique in their vario-colored flower-like designs. They are really composed of jasper (chalcedony), quartz and pyrites. All these pebbles are prized by tourists, who gather them and have them polished and mounted for pins and other ornaments, as they make handsome pieces of jewelry.

Beryls, which include emeralds and aquamarines, are plentiful in the mines of Riverside and San Diego Counties. Pink or rose beryl, hitherto rare, is found in several localities of the gem-region in Southern California[;] also a green and yellow variety, and one of a peculiar opaque deep-blue. Emeralds of good quality have not yet been discovered, but the stone called California emerald is interesting.

|

| From the Little 3 Mine. Natural blue topaz, Ramona, California, 31.80 ct. Cut by Carl Larson, father of Pala International’s Bill Larson. Bill found the rough in 1968 during his successful mining venture with Josie Scripps. Courtesy of Bill Larson Collection. (Photo: Orasa Weldon) |

Sapphires are obtained from San Francisquito Pass. Beautiful topaz, white, light-yellow, sea-green and sky-blue, is plentiful in the mines near Ramona, San Diego County. Some of the crystals weigh a pound.

Spinel-ruby comes from San Luis Obispo County, and Humboldt County furnishes a blue-spinel of good color.

Tourmaline, as before mentioned, [in] pencils of all sizes, pink, green, blue and red, are taken from the San Diego County mines in large quantities. The small specimens first came to notice through a scientist who found the Indian school children playing with the “pretty, colored glass pencils.”

I saw the tourmalines in connection with kunzite in the mines. It was interesting to examine the gems in their native state; the workings as a rule being near the surface, look easy to mine. One huge pencil, of a deep rose-red, which they showed me, measured five by seven inches, and was worth upwards of $2,500. Until lately tourmalines have not been universally used as gems, though China has long prized the pink tourmaline as a jewel. The tourmaline mines in California are considered the most remarkable in the world. The pencils, often forming clusters of a dozen or more in banded colors, fastened to rock-crystals, are royal specimens.

|

| Himalaya Mine tourmaline figurine carving from 1958. From the jade factory in Beijing. Dimensions: 5.5 x 2.2 x 1.2 cm. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

In this same district, in the lithia mines, associated with the lithia, are found gem-tourmalines and kunzite. Quartz-crystals of all colors come also from this locality. Of these, amethyst, Spanish topaz and rose-quartz are favorite gems. To the non-crystalized quartz belong chalcedony, carnelian, chrysoprase, the agates, onyx, moss-agates, the true moonstones and jaspers, all of which are found in pebbles or pockets, in various parts of California. The chrysoprase principally comes from Tulare County. True moonstones of fine quality but very small in size are found in the Funeral Mountains, Inyo County.

Several varieties of opal are reported from different localities, but few of the precious fire-opals. Some of the California opals are almost an amber yellow. Fire-opals, in small quantities, appear in seams and pockets in the vicinity of the Mojave Desert. A peculiar glassy variety of opal, hyalite, often called California diamond, is found in Lake County near Seigler Springs.

Turquoise of fine color and in great quantity, the mines covering an area of many miles, was located near Manvel, San Diego County, in 1898. Legend ascribes these mines to have originally belonged to the Desert Mojave tribes, and the remains of cave dwellings and utensils for working the ore, discovered near the mines, lends proof to the story. Turquoise ornaments, and the gems cut and uncut, are on exhibition in the gem stores in Los Angeles in great abundance and at very reasonable prices.

Pearls from the oyster and from the abalone, are among the gem productions of the State. The shell of the abalone is also made into various ornaments that sell readily to tourists. The rich colors of beautiful green and violet shades make handsome bracelets, chains and other pieces, but the abalone shells are so common in California that the residents care little for them.

Datolite, another gem-material, is strewn over the deserts of San Bernardino and Inyo Counties, and is also found at Fort Point, San Francisco. It is found both in small glassy crystals and in masses. The colors are white, creamy grey, pale green, yellowish, reddish and amethystine.

A remarkable mass of rock-crystal of enormous size was unearthed at Mokelumne Hill in 1898. Tons of the rock were taken out and shipped to New York and to other countries. A giant crystal, surrounded by one hundred and sixty smaller ones, weighed over a ton. One of these flawless crystals sold for $3,000, and was used for making crystal balls.

Mariposite is another mineral that has been shipped to China in quantities, its charming green color used in place of jade.

This is but the beginning of the gem industry in California; the mines are young, and new gems are continually being discovered, which appears to be essentially Californian. Just lately came information of a new stone of an attractive blue color, which, in the deeper tones, showed a violet tint. It rivals in color the sapphire, and is more brilliant, but not so hard. It came from San Benito County and was christened benitoite.

|

| Benitoite. Above, an oblique hexagonal cut, 1.55 ct, 8.03 x 5.53 x 4.31 mm, Inventory #18850. Below, cushion cut, 0.99 ct. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

|

The gem shops of Los Angeles and San Diego are dazzling in color and brilliancy, due chiefly to the California stones, but so little is known of the value and variety of the native gems, that many people will not believe in their genuineness; and too often are they sold, to those who do not know of California’s wealth of native gems, at large prices, as stones from foreign countries.

I have visited some of the mines in my wanderings, studied the gem material, and gathered specimens from various parts of the State, and I know that Californians, if they desired, could gather their own gems from the hills and possess stones as lovely as the world can boast. The residents of the State should develop the gem mines, instead of allowing the product to be taken out by alien [sic]. I think I am safe in asserting that it would be hard to secure many native gems in the jewelry stores of San Francisco. Why? Because the output of the mines is sold before it is dug from the earth to rich firms of other State [sic] and countries; also a local demand for the gems is lacking. People of the State go abroad to buy their gems, partly through ignorance of what they have at home, partly because they mistakenly think the foreign stones are better. The people of other countries do not seem to think so.

The men who own the mines generally do the work themselves, as it is difficult to find honest labor, and while the mining looks easy, it is slow, and must be done with care not to injure the gem material. There is also a need of a greater number of skilled, honest lapidaries, either from foreign countries, or artisans trained to the trade in schools, to cut the gems well, and reasonably; then shall the demand for them grow and bring rich harvest to the State, instead of the uncut output of the mines traveling to foreign countries, a meet punishment for the ignorance and neglect of such treasures. However, there is some excuse, as the men of the State Mineralogical Bureau complain that it is most difficult to get information about new mines, so carefully are their secrets guarded lest thieves or prospectors divide the spoils, or lessen the value by increasing the output.

|

| From Pala, California. Three examples of peach-colored morganite. From left: round, 2.26 ct, Inventory #20766; emerald cut, 1.97 ct, Inventory #20767; kite cut, 1.99 ct, Inventory #20768. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

At present this is the array of gems in California: Diamonds, kunzite, tourmaline, topaz, spinel ruby (red and blue), emeralds, aquamarines, garnets, amethysts, jaspers, opals, chrysoprase, sapphire, Californite (jadite), chalcedony, moonstones, chrysocolla, azurite and malachite, lapis-lazuli, abalone, ornamental and shell pearls, turquoise, and the new gem, called benitoite.

Most of the 24 varieties mentioned are well known gems that our people bring from European countries, and yet they can collect as beautiful stones, with the exception of diamonds, in their own State.

|

The Gem Deposits of

Southern California

By Richard H. Jahns

An article originally published in Engineering

and Science Monthly, Vol. 11, No. 2,

February 1948, pp. 6–9

ON a warm June day nearly 76 years ago, Henry Hamilton was picking his way along the brushy southeastern slope of Thomas Mountain in the Coahuila district of southern California’s Riverside County. As he crossed a small gullied area, he noticed several rough mineral fragments of attractive pink and green color. Carefully tracing the occurrence of this loose “float” material to its source higher on the hill, he encountered a ledge of light gray rock in which a few irregular cavities were lined with crystals of quartz and other minerals. Among these others were beautifully transparent pencil-like crystals of red, pink, green, and blue color. These constituted the first California discovery of gem tourmaline, a material that already had been mined in eastern parts of the United States.

A little mining was done at the new locality, and some excellent gems were obtained. As the interest of other men was quickened by Hamilton’s success, additional deposits were soon discovered in the same general area, but it was not until nearly 20 years later that any important find was announced. This, in an area 24 miles to the southwest, was an occurrence of tourmaline with large quantities of the lithium-bearing mica, lepidolite. The deposit was exposed on a hill slope immediately north of the little mission town of Pala, on the San Luis Rey River. In addition to large quantities of lithium minerals, it yielded numerous specimens of lilac-colored lepidolite with coarse sprays of deep pink tourmaline. These found favor in museums and collections the world over.

|

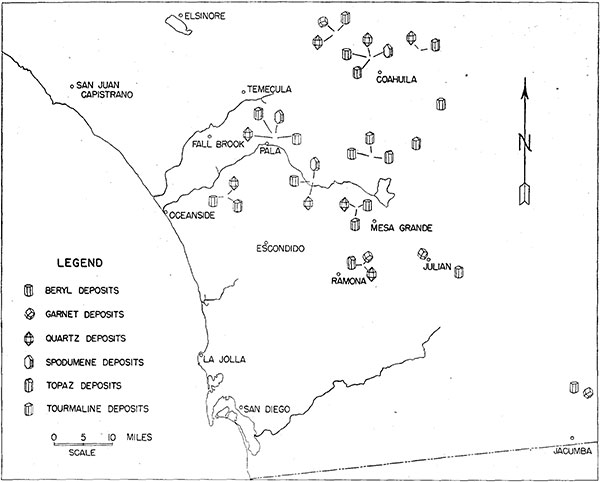

| Fig. 1 Map of southwestern California, showing locations of principal gem deposits. |

The greatest discovery of all was made still later, in 1898, when several blue, green, and red crystals of tourmaline were shown to cowboys by Indians living near Mesa Grande. The source of this material was found to lie on a high wooded slope south of the San Luis Rey River and about 11 miles south of Palomar Mountain. This ledge became the site of the world-famous Himalaya Mine, the greatest producer of gem tourmaline in North America.

Tourmaline was not the only mineral involved in a series of spectacular discoveries made during the period 1902–1905. Frederick M. Sickler, while working a lepidolite deposit a short distance northeast of Pala, encountered numerous transparent masses of a mineral colored in delicate tints of pink, lavender, lilac, and blue-green. These were subsequently identified as a rare, remarkably clear variety of the lithium-bearing mineral spodumene. The pinkish to lilac-colored types were given the name kunzite, in honor of Dr. G. F. Kunz, who first identified them in his capacity as mineralogist for Tiffany and Company of New York. Kunzite thus is one of California’s own minerals.

Additional spodumene deposits soon were discovered in the Pala area, and mining for this mineral, tourmaline, and lepidolite led to recognition and recovery of fine transparent quartz crystals and a beautiful pink to deep peach-colored variety of beryl. The aquamarine and emerald varieties of beryl were well known at the time, but this type was new, and was named morganite in honor of the noted financier [J. P. Morgan]. Such beryl also was encountered during mining in the Mesa Grande and Rincon districts.

Tourmaline was found on the slopes of Aguanga Mountain, near Palomar Mountain; at several places in the Mesa Grande area; near the town of Ramona; and at numerous other localities during subsequent years. Colorless to blue topaz, some of it in large, perfect crystals, was discovered at several Aguanga Mountain and Ramona localities, and subsequent mining yielded stones of quality equal to that of the best material obtained from Brazil. In addition the essonite, or hyacinth variety of garnet was found in the Ramona deposits, chiefly as honey-colored to orange-red transparent crystals. It also occurs in the Mesa Grande area; in the vicinity of Jacumba, far to the south near the Mexican boundary; and at several intervening localities.

The locations of the principal gem-producing areas of southern California are shown in Fig. 1. All are in the province of the so-called Peninsular Ranges, a series of ridges and mountains that extends southward from the edge of the Los Angeles Basin. This great highland mass separates the Salton-Imperial depression on the east from the coastal areas on the west, and also forms the “backbone” of much of Baja California. It is characterized by medium- to coarse-grained igneous rocks that range widely in composition.

|

| Fig. 2 Typical well-developed “line rock.” This garnet-rich rock has been used locally as a decorative stone in fireplaces and garden walls. Hammer at top of boulder is for scale. |

All the gem materials and minerals occur in pegmatite, a granitic rock characterized by extreme coarseness of grain. The pegmatite ordinarily forms dikes, and these tabular masses range in thickness from less than an inch to 100 feet or more. In most places the pegmatite is surrounded by other, less coarse-grained igneous rocks of more basic composition. In most areas the dikes trend north to north-northeast and dip westerly at gentle to moderate angles. Although they consist chiefly of graphic granite, a peculiarly regular intergrowth of quartz in microcline feldspar, careful examination discloses numerous variations in their composition and internal structure.

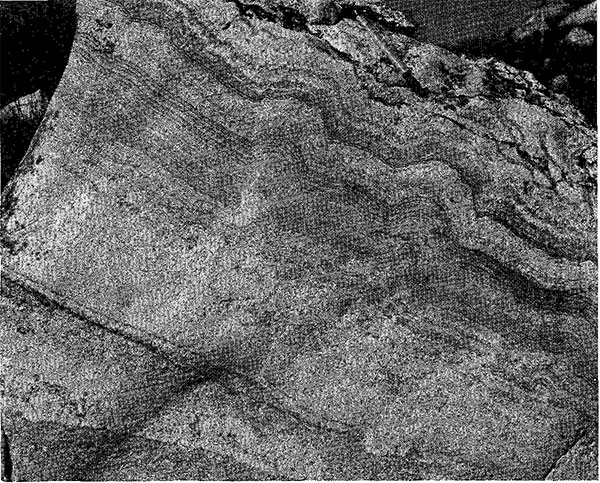

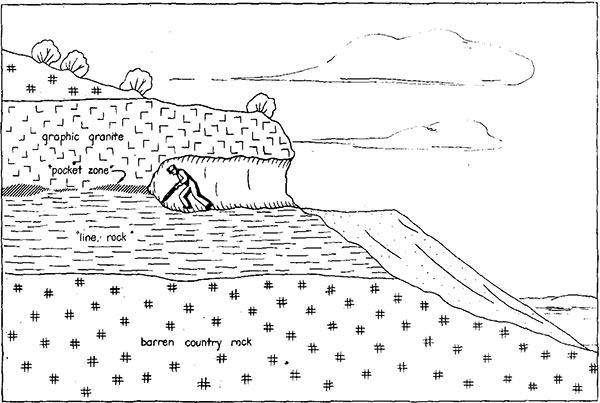

Many of the pegmatite masses are very regular in thickness and attitude, and most of them contain little or no gem material. Others are “two-ply” features, with upper parts of graphic granite and lower parts of a strikingly layered, much finer-grained rock that consists mainly of sugary albite feldspar with garnet, black tourmaline, or both minerals. The latter has been termed “line rock,” owing to the appearance of its many thin, sub-parallel garnet- or tourmaline-rich layers on most outcrop surfaces (Fig. 2). A little of this material has been used as an ornamental stone, but none of it has yielded gems.

|

| Fig. 3 Diagrammatic cross-section showing distribution of the gem-bearing “pocket zone” and the other rock types characteristic of many southern California pegmatite dikes. |

In the central part of some dikes, commonly along or near contacts between “line rock” and overlying graphic granite, is the so-called “pocket zone,” “pay streak,” “clay layer,” or “gem strip” (Fig. 3). Ordinarily this is an irregular series of tabular or pod-like masses that are rich in quartz. Associated with the quartz are albite, microcline, and orthoclase feldspars, muscovite and lepidolite micas, tourmaline of various colors, beryl, and rarer minerals. These masses generally are surrounded by pegmatite rich in muscovite and coarse prisms of black tourmaline.

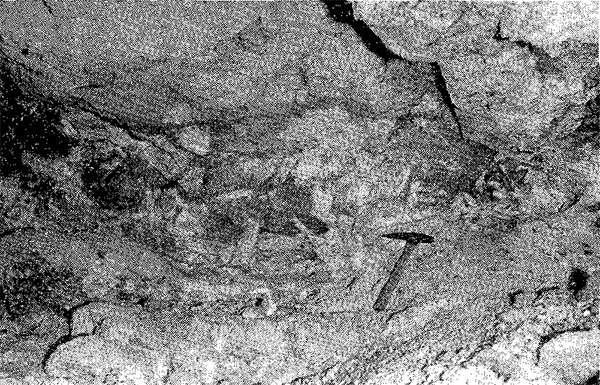

Some well formed quartz crystals weighing 100 pounds or more have been encountered during mining, although few gem crystals of quartz or other minerals exceed six inches in maximum dimension. The gem material of best quality is found embedded in a pink to pinkish brown clay, which is thus regarded by miners and prospectors as a very favorable indication of “pay stones” (Fig. 4). Some of the gem crystals are loose in the clay, some are attached to other minerals that line the clay-filled “pockets,” and a few are wholly or almost wholly embedded in solid pegmatite.

|

| Fig. 4 “Pay streak” in Pala Chief mine northeast of Pala. Crystals of spodumene (white) are embedded in a matrix of clay and quartz (dark gray). Some of the spodumene crystals contain material of gem quality. |

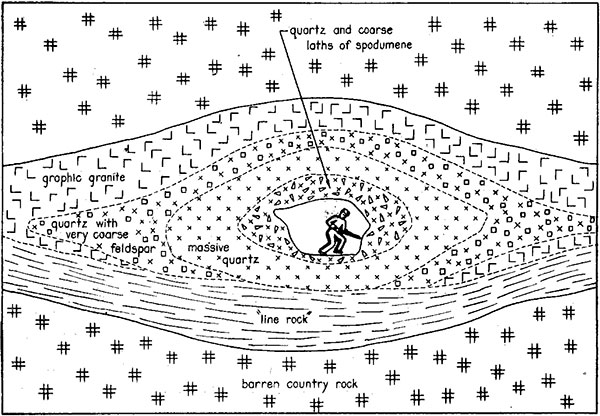

Most of the pegmatites that contain gem tourmaline, topaz, garnet, or beryl are 5 to 20 feet thick, although there is little systematic relation between thickness and gem content. Indeed, the famous Himalaya pegmatite, in the Mesa Grande district, was only 1 to 5 feet thick where richest in gem minerals. There is a definite relation, on the other hand, between the occurrence of kunzite and the local thickness of spodumene-bearing pegmatite dikes. Such dikes characteristically thicken and thin, or “pinch” and “swell,” as traced along their outcrops. The central part of each bulge or “swelling” is commonly marked by a pod-like mass of quartz or of quartz with long, thin, lath-like crystals of spodumene (Figs. 5 and 6).

The spodumene is opaque and white to pinkish in color, and much has been thoroughly decomposed to a clay-like substance. Inside some of the crystals, however, are fragments of clear kunzite, which appear to represent those parts of the crystals that escaped alteration. The proportion of clear material is rather high in the crystals nearest the centers of the largest pegmatite bulges, and a very few laths are entirely unaltered. Gem crystals of this type are known to reach thicknesses of 2 inches and lengths of nearly a foot, but unfortunately are exceedingly rare.

|

| Fig. 5 Idealized cross-section of a typical spodumene-bearing pegmatite in southern California. |

The mining of pegmatite gems in southern California reached its peak during the decade 1902–1912, when material valued at more than $1,500,000 was marketed. Tourmaline, which represented most of the output, was graded on the basis of size, color, transparency, and freedom from bubbles, inclusions, and other imperfections. Nearly all the gem crystals are shaped like a short lead pencil, with diameters of most ranging from one-eighth inch to four inches or more. They are characteristically hexagonal, with flat or nearly flat terminations. A wide variety of colors has been found, but red, pink, salmon, green, dark blue, and black are most widespread. Many crystals are bi-colored or multi-colored, with sharp or gradual changes from one end to the other or from the interior outward. Some crystals with pink interiors and green rims are known as “watermelon” tourmaline.

|

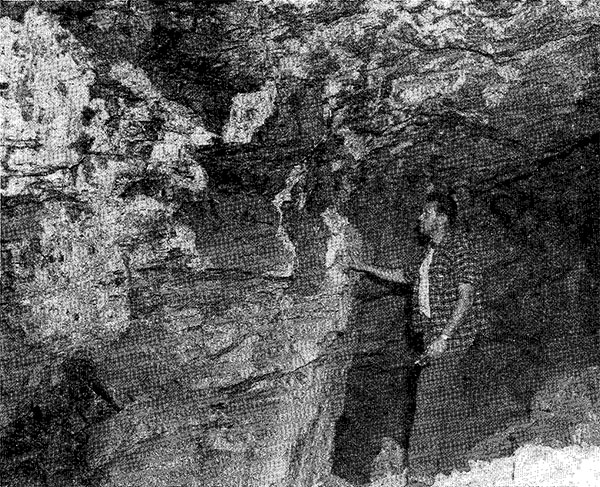

| Fig. 6 Don M. George Jr. examines spodumene-bearing pegmatite in the Stewart mine, near Pala. Spodumene crystals (light gray) are abundant in the roof over his head, and lepidolite mica forms most of the rock below his hand. |

Most transparent crystals of high quality were cut into gems, which commanded prices of $2 to $10 per carat. Current prices are somewhat higher than this. Much pink material of slightly inferior grade was sold to Chinese markets, where it was highly prized as carving material. Thousands of crystals, representing a wide range of quality and size, also were marketed as specimens in all parts of the world. So much tourmaline was sold during the “golden decade” of mining, however, that the market collapsed shortly before World War I, and only during recent years has it shown signs of recovery.

During World War II, a little tourmaline of deep green and blue color was sold from the Pala district. This represented material left over from previous production, and was used because of its piezoelectric properties. The current demand for such material, as well as for gem stock of highest quality, far exceeds the present available domestic supply.

The rough crystals of kunzite are blade- or lath-shaped, and nearly all are deeply striated and grooved (Fig. 7). Most are small, with lengths of two inches or less, but some nearly a foot long and weighing 24 ounces or more have been recovered during mining. The limiting factor for size of top-quality cut stones is the thickness of the source crystal, as the deepest colors are obtained only when the stones are viewed parallel to the long axis of the crystal. The mineral is a very difficult one to prepare as a gem, owing to its two directions of perfect cleavage and hence its tendency to break near the edges during cutting. However, it yields stones of exceptional beauty.

Current prices for facet-cut stones of this high quality range from $2 to more than $25 per carat, depending chiefly upon the nature and depth of their color. Kunzite is so rare that it also has considerable value as a specimen material. It has been mined sporadically during recent years in the Pala district, and three mines are being reopened for systematic operation at the present time.

|

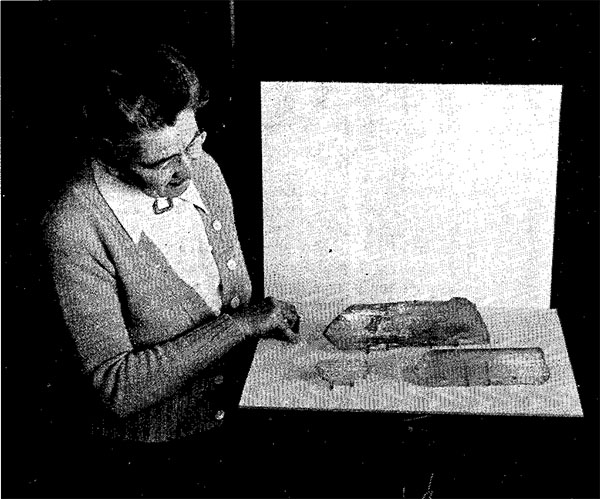

| Fig. 7 Leonora S. Reno, secretary of the Division of the Geological Sciences, admires three giant crystal fragments of gem spodumene. The largest ones are two very remarkable specimens from the collection of T. W. Warner, Pasadena. |

Colorless to blue topaz has been mined chiefly from deposits near Ramona and on Aguanga Mountain (Fig. 1). It has found a ready market, commanding prices of $5 to $15 per carat in the form of facet-cut stones. Much specimen material has been sold as well.

Quartz, garnet, and both aquamarine and pink to salmon-colored varieties of beryl represent only a small proportion of the gem production of southern California, in terms of both bulk and value, but they are widespread in their occurrence and in their distribution in gem and mineral collections. A large pocket of peach-colored beryl crystals was encountered during recent wartime mining for quartz crystals of radio grade in the Pala district, and other crystals of similar form and color have been encountered from time to time in the search for kunzite. Still other occurrences have been reported during recent years from deposits in Riverside County.

The moribund gem mining industry of southern California, with a total recorded production valued at more than $2,000,000, is currently showing signs of revival. Although “bonanza type” operations probably are gone forever, it will be interesting to see whether a gradually rising market and a modern approach to pegmatite geology and mining will sustain activities at somewhat less spectacular levels.

Note: Palagems.com selects much of its material in the interest of fostering a stimulating discourse on the topics of gems, gemology, and the gemstone industry. Therefore the opinions expressed here are not necessarily those held by the proprietors of Palagems.com. We welcome your feedback.