Gemstone and mineral mining

in Pakistan’s mountains

|

A reprint from InColor

by Jim Clanin, geologist and gem mining expert

One important aspect of ICA’s engagement in the area of Social Responsibility is its ability to facilitate expert assistance and consulting services through its international network of professional members involved in mining, processing, education, marketing and distribution. In this respect, the government of Pakistan has launched an initiative for the development of the gem and jewelry sector funded by the US Agency for International Development, USAID. Jean Claude Michelou, ICA’s former vice president and current chairman of the Social Responsibility Committee and director of communication, prepared a wide-ranging development plan. He invited geologist and gem mining expert Jim Clanin to join the program and assess the gemstone mining situation in northern Pakistan as well as making recommendations for the improvement of working conditions and mining techniques regarding high-altitude gem deposits.

The following article is an excerpt from Clanin’s report and recommendations that followed his visit to the area in the summer 2007 which relate to human conditions and environmental issues. They were complemented by the design of a curriculum for sustainable training of miners and local engineers for the reinforcement of the foundation of the value chain of supply within the gemstone sector.

The article:

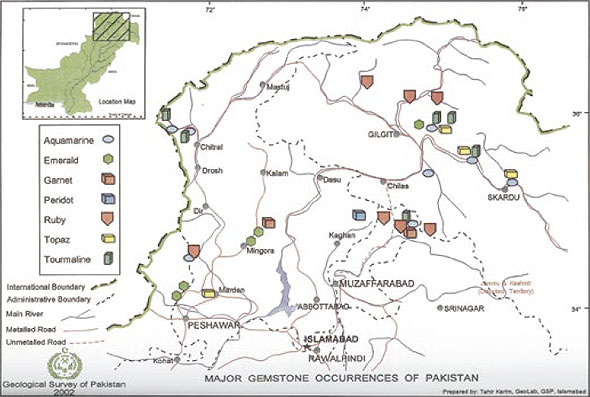

I went on a reconnaissance trip in July 2007 to evaluate the various gemstone mining areas in the Federally Administrated Northern Areas of Pakistan. The trip was limited to the Gilgit, Skardu and Astore districts due to time and security. Gemstones and minerals have been produced in this mountainous region of Pakistan for nearly 40 years. Mountainous regions are geologically active areas that expose a greater amount of rock outcrops and give prospectors an advantage in locating gem and mineral deposits. They also give rise to numerous logistical problems, some of which are extreme.

The Himalayas are the youngest mountain range in the world, and their pegmatites, which contain a variety of gemstones, are only a few million years old. This region has the greatest vertical differences found anywhere in the world as well as the world’s seven highest peaks. At Nanga Parbat, in Astore, the mountain peak is more than 20,000 feet above the valley floor. Tourmaline, aquamarine, topaz, garnet and apatite come from granitic pegmatite deposits, while emeralds, rubies and sapphires come from metamorphic and hydrothermal deposits that tend to be regional and cover a larger area.

|

| A high-altitude gem-mining platform in Pakistan. (Photo: Vince Pardieu, ICA/ fieldgemology.org) |

Prospecting in a region with near vertical cliffs that rise 3,000 to 4,000 feet or higher is a nightmare. Mining a deposit in an environment like this is even worse. At such elevations, pockets are practically always frozen, internal combustion engines do not operate, the air pressure is too low for pneumatic equipment, and the mining season is generally very short.

The granitic pegmatites of these areas produce a vast assortment of gem minerals, but it is difficult, if not impossible, to predict in advance what their production will be like. Even though the mineralogy might dictate the presence of colored tourmaline pockets, for example, the quality of the contents may be worthless. Most gem mines are operated by hobbyists or worked by small groups of artisanal miners using the most basic methods mainly in remote places. In many locations, everything must be carried up either on horseback (or donkey) or by the miners themselves.

|

| Miners camp at Chumar Bakhoor overlooking Hunza valley. (Photo: Jim Clanin) |

Before we attempted to visit any mine workings we met with groups or associations of miners. We explained our mission to the people of each area and were usually given a guide to take us to mine sites. We had almost no problems gaining the trust of the miners, and were able to visit many different workings. We had to turn down some mines due to their inaccessibility or dangerous conditions.

The mining season in the areas we visited depended on the altitude of the deposits. In some areas the work window is from June to September or October, and in others it might be from July to October. Some miners work the higher elevations in the summer and then move to the lower elevations during the winter, so they can mine year-round.

Rubies of the Hunza valley

The ruby-bearing host rocks in Pakistan are part of the Baltit group sequence and are contained in the Karakorum metamorphic belt north of the main Karakorum thrust. This meta-sedimentary unit can be traced from the Afghanistan border to the Indian border.

We visited six sites in five days in the Hunza Valley area that produce or have produced ruby. These workings are located right on the Karakoram highway on the east side of the Hunza river.

One recent discovery near the village of Bisil in the Basha Valley has the same mineral assemblage as the deposits in Hunza valley more than 100 kilometers to the west. Based on the geology and mineral assemblage at each locality the Bisil discovery is probably an eastern section of the same carbonate shelf that formed during the Eocene in the Tethys basin.

Ganesh was the northernmost spot we visited, with workings on the east side of the Hunza river. Just across the river from Ganesh, Global Mining Corp. is beginning to mine ruby-bearing marble at Gupa Nala. Another deposit is located just above the village of Aliabad. The Dhorkan workings, south of the Aliabad and Hachinder workings, are the southernmost that we visited.

|

| Accessing the ruby deposits of the Hunza Valley in Northern Pakistan. (Photo: Jim Clanin) |

Many of these deposits have the same general kinds of minerals: phlogopite, margarite and muscovite micas, zircon, spinel, magnesium tourmaline, pyrite, rutile and graphite, all of which are hosted in marbles.

Other than Global Mining Corp., we did not meet any other miners working these ruby deposits. But we could see and smell signs that explosives had been used recently, probably illegally. This is an extensive, continuous regional mineral deposit that a corporation might well be interested in working, as the presence of Global Mining Corp. indicates.

Most of the workings we visited were excavated by the Pakistan Mineral Development Corporation in the early to mid-1970s. A report on the project from 1978 states that the producing marble deposit is 2,100–3,000 meters thick and extends 25 km on strike. The average carats per ton of ruby, sapphire and red spinel from eight samples is given as 16.68 carats/long ton, with a net reserve of 161,227.97 long tons, or approximately 537.8 kg of gem material. However, there were too few samples in too few areas to come up with reliable statistics on reserves.

Pegmatites

The pegmatites of Chumar Bakhoor belong to a well-organized miners’ association in the village of Sumayar. This association allows 55 groups of six men each to work the pegmatites, and the money made benefits the entire village. Since these pegmatites are all found within a small area at an elevation of around 4,800 meters, the working season is from late July to sometime in October.

The pegmatite of the Bulachi area, lies between the village of Shengus and Astak on the Gilgit-Skardu road. The pegmatite swarm in this area includes deposits along the Indus river, the area around Haramosh, the Stak Nala mines, and the mines within the Astore district on the south bank of the Indus river. At Stak Nala the pegmatites are lithium rich (LCT-type) and produce multicolored tourmalines rather than black ones. It was rumored that colored tourmaline had been found somewhere in Astore district, which would indicate that more LCT-type pegmatites have been discovered.

|

| Hauling supplies to a gemstone mine in Pakistan. (Photo: Vince Pardieu, ICA/ fieldgemology.org) |

Along the Indus river, pegmatites that are being worked are visible for about 7 km on the opposite bank of the river from the road running east from Shingus. A few workings are to be seen on the side of the river with the road, all placed so that rock will not fall on the road. These are granitic pegmatites that produce aquamarine, black tourmaline, topaz, apatite and garnet. There are reported to be hundreds of these pegmatites, many of which are located on near-vertical faces of the mountains, so that miners must rappel down on ropes to gain access. Four villages own the pegmatites on the south side of the Indus river, and some 400-500 miners have been working the area for 14–15 years.

Another mining site we visited was at the base of Haramosh near the village of Shah Toot. Here the pegmatites are spread out so that few workings are visible from the village. The only workings we were allowed to see consisted of a shallow open pit in a vertical pegmatite. Unlike the other workings we visited, this dump showed no sign that pockets had ever been found there, although the locals said the small hole had yielded 1.5 million Pakistani rupees worth of goods (about $25,000). They said there are more than 200 mines in their region, and they have been working them for about 20 years.

Due to global warming, the glaciers in the area have been receding and exposing more areas for prospecting. Our guide from Shah Toot told us the Mani glacier has receded several miles and exposed new sites high up in the mountains. I believe these pegmatites are part of the same Bulachi pegmatite swarm, but the frequency of the pegmatites is far lower at Haramosh.

The mines of Stak Nala are supposed to belong to the village of Tookla, but the locals say that many outsiders dig there. These are LCT-type granitic pegmatites that produce tri-colored tourmaline, a highly valuable mineral. The locals say there are 40 mines in the area. The Gemstone Corporation of Pakistan (GCP) worked Stak Nala systematically in the 1980s, and when it left it blasted the tunnels it had used closed. Only one is open today, presumably reopened by the local miners. They say they would like to work the tunnel, but more of it caves in each time they blast. I suggested building rock walls to shore up the walls, which appear to be highly fractured due to past over-blasting by the GCP.

The pegmatite swarm of the Shingar, Braldu and Basha valleys, unlike that at Chumar Bahkoor, is spread out over an area of about 150 square km. There are no trails leading to producing areas, only to isolated pegmatites or mines. The morning we awoke in Dassu, we could hear blasts from mining all over the mountains on both sides of the river, starting at 6: 30 am and lasting all day.

|

| A breathtaking cliff at a gem deposit in Pakistan. (Photo: Vince Pardieu, ICA/ fieldgemology.org) |

Mining dumps rise from the river level to the top of the mountains, some 3,000 meters overhead. Some mines appear to be holes in the mountainside without dumps, since the slope is nearly vertical. We talked with officials of the Baltistan Gem and Mineral Association in Skardu, who are trying to organize the miners in these valleys. The association took a survey in 2003 and found that 4,500 households are involved in mining in this region. Each household has from three to 10 people involved directly in mining, so this area has the largest number of miners of any we visited.

It was rumored that colored tourmaline had recently been discovered somewhere in the mountains around Dassu. One mine we saw had flawless quartz and topaz in the dumps, as well as pocket feldspar and micas. We had a group meeting with miners in Dassu, who said that there are 200 groups of men working there year-round, some in tunnels 150 to 180 meters deep. In these longer tunnels they blast once and then quit for the day, letting the tunnel air out overnight. To the west of the Braldu valley lies the Basha valley. This is the western portion of the same pegmatite swarm. There are fewer deposits than to the east in the Braldu valley. Near the village of Sibibi, we were shown a working pegmatite which required a rope to reach.

Health, safety and the environment

According to the Pakistani government, none of the country’s mineral-producing areas have ever enjoyed modern mining equipment, safety standards or the expertise of mining engineers. Currently, most Pakistani miners use Chinese-made, gasoline-powered rock drills both on the surface and underground. There is no ventilation, and miners say they only stop work when they can no longer light a fuse due to either a lack of oxygen or air pollution. All of the approximately 40,000 miners in northern Pakistan complain of lung problems from both silicosis and carbon monoxide poisoning. However, the leading causes of death in this extreme environment are being buried under rock falls or falling from a perch on a sheer cliff face.

The ruby deposits of the Hunza valley and other lower elevation deposits can be worked with pneumatic equipment, thus eliminating the dust and carbon monoxide problems. But in the Bulachi area pegmatites and those of the Shingar, Basha and Braldu valleys, the miners are stuck using the gasoline-powered drills due to the extreme inaccessibility of the deposits and/or the elevation. Miners literally hang from ropes on near-vertical cliff faces and use the gasoline-powered drills while dodging falling rocks.

I do not believe that the impoverished miners will ever stop mining and wait for the necessary improvements. But some things could be done immediately. Disposable dust masks are necessary, but are not available in the region. Large quantities should be on hand for quick and easy replacement, otherwise the miners will try to reuse the old contaminated filters.

Conventional ventilation systems do not work in this mining environment. A machine that is lightweight, easily transportable and repairable, human-powered and can be produced in Pakistan could be easily designed. This machine should be able to push air at least 90 meters, with an ideal capacity of 150 meters. To alleviate the carbon monoxide poisoning problem, a standard 7.5 meter extension should be added to the drills’ exhaust port that would carry the fumes away from the operator.

|

| Drilling in a tunnel at the Nangimali ruby deposit in Pakistan. (Photo: Vince Pardieu) |

Drilling and blasting techniques also must be improved. I was told that the miners drill one to three holes in a round to be blasted and are lucky if they make 30 cm of tunnel a day. The holes are no deeper than 45 cm, and the miners use a petrol drill suitable for drilling vertical holes, not horizontal ones. They need to drill more horizontally and use a drilling pattern to improve breakage and do less damage to any pocket in the vicinity. People should also be trained in basic first aid for emergencies, as well as extreme mountain climbing techniques. Mountain climbing equipment should be made available to the miners.

Gemstones for the benefit of local residents

The government of Pakistan would like to lease all its gem deposits to corporations and take the production out of the hands of the locals. Regional deposits are believed to be suitable for corporations, but the pegmatitic deposits should remain in the hands of the local villagers who currently operate these mostly inaccessible and unpredictable deposits. In some areas, there were well-organized miners’ associations, while in others there was little organization, and in still others the locals had no idea what was being mined in their own backyard.

Each mining area should create its own miners’ association which must be able to respond with rescue teams to dig out miners trapped by cave-ins or other disasters, and transport them to hospital. They could also be distributors of personal protective equipment like replacement dust masks, that would serve as the point for miners to sell their goods to the brokers, thus improving their profit or income opportunities.

For example, Sumayar village needs a common selling place where miners could deposit their specimens and brokers and buyers could view and buy them. Having an auction once a year near the end of the mining season pitting one broker against another would help improve local price levels. Whatever doesn’t sell would go to the Sumayar mineral store where specimens and gems could be negotiated, at reasonable prices, by visiting dealers and buyers on a “cash and carry” basis instead of a promise to pay great sums later.

This article appeared in the Spring 2008 edition of InColor, which is published by the International Colored Gemstone Association (ICA). We are grateful to Jim Clanin and ICA for granting us permission to reprint this article. The article is copyright © 2008 Jim Clanin.

See also:

- Pakistan’s Gemstones: An Overview

- A Letter from Pakistan: True adventure from Pala International’s daring suppliers

- Pakistan: 2006 – A Year in Review

- Pakistan Update – 8/15/07