The following essay was written by Pala International president Bill Larson for a new book, Ruby & Sapphire: A Collector’s Guide, authored by Richard W. Hughes with photos by Wimon Manorotkul and E. Billie Hughes. See more on the book here.

TWIN TREASURES

|

As a young boy I was fortunate to be introduced to the world of mineral collecting. I grew up in Fallbrook, California, which provided me with two magnificent opportunities. First is that Fallbrook is just miles from the world-famous Pala pegmatite district. Storybook mines that produced tourmaline, kunzite and spessartine garnet were literally on my doorstep.

The second was human treasure, as opposed to natural. At an early age I made the acquaintance of a number of individuals who became my mentors, teaching me the finer points of mineral collecting. These included world authorities in the field, such as John Sinkankas (b. 1915; d. 2002) and Eduard Gübelin (b. 1913; d. 2005), as well as those less well known, like Josie Scripps (b. 1910; d. 1992) and Ed Swoboda (b. 1917; d. 2013). This combination allowed me to develop my skills as both a collector and dealer.

INSIDE VS. OUTSIDE

As someone who has been intimately involved in selling both mineral specimens and precious stones, I would like to focus on the fundamental difference in collecting crystals, as opposed to finished gems and jewelry. With precious stones, it’s all about the inside, whereas with crystals, the opposite is true. When judging a gemstone, the gem’s internal perfection (clarity and color) is extremely important in determining value. But crystals are valued in large part based on the perfection of their external surfaces. Even one tiny chip or “ding” can have a vast effect on value and, unlike a finished gem, cannot be removed by polishing. Color and clarity are still important, but with mineral specimens there is more forgiveness when compared with gems.

What other general advice can I give the budding mineral collector? I can do no better than to refer you to the book of my close friend, Wayne Thompson, who summed up the key building blocks in his magnificent Ikons, Classics and Contemporary Masterpieces (Thompson, 2007). On that note, let’s specifically examine a few points of collecting ruby and sapphire crystals.

RUBY

I have always been fascinated with ruby, both as a crystal and gemstone. Crystallized ruby is relatively common. But when rubies are found as fine, pure red translucent or transparent single crystals (or in matrix), they become some of the most rare mineral pieces on the planet. As an advanced mineral collector I have only seen a handful that qualify as world-class ruby specimens and of those, only from Mogok (Myanmar) or Luc Yen (Vietnam).

|

| Two Burmese rubies. Both are incredibly scarce, but the gem-quality crystal at right is decidedly more rare. (Stones: Pala International; Photo: Jeff Scovil) |

That said, Burma and Vietnam are not the only rubies worth purchasing. Jegdalek, Afghanistan has produced ruby specimens approaching the quality of those from Burma and Vietnam. Locality collectors can also easily find rubies from lesser locales, but these are not necessarily beautiful specimens. With locality collecting, it’s more important to obtain the best specimen the location has provided; this can be interesting and tell a great geological story.

What are some of the other localities? In North America, small ruby specimens are known from Montana, North Carolina and even New Jersey. Ruby crystals have also been found in Switzerland and Macedonia.

Africa has rubies in many countries. The best are from Winza (Tanzania), along with the new finds in Mozambique and Madagascar. These localities are producing a few wonderful single crystals.

Rubies in green zoisite from Longido (Tanzania) have been known for nearly a hundred years; some are quite attractive. India produces large numbers of ruby crystals. While they are poor in transparency, they can sometimes be of enormous size (as large as 10 x 5 inches).

Small doubly terminated pink-red crystals come from Sri Lanka. While they may be glassy in some areas, often these are too water-worn for collectors. Small but translucent ruby clusters in calcite are also found in Nepal and can be quite attractive.

From this you can see that most of these localities have not produced what would be considered a world-class mineral specimen. And one final point must not be overlooked: the extraordinary rarity of fine ruby is compounded by the fact that most of the finest specimens have been cut over the centuries and are now gemstones.

SAPPHIRE

Geologically speaking, sapphires are more common than ruby. However, with the exception of the finest Mogok rubies, the really top gemmy blue and/or yellow sapphire specimens are even more rare than most rubies. Only a few world-class sapphires from Sri Lanka’s or Mogok’s gem fields have been preserved.

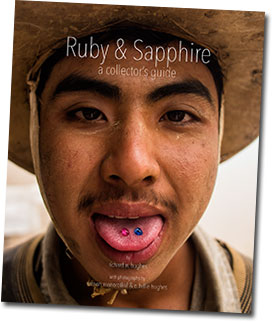

|

| The beauty of nature is revealed through this complex twinned sapphire crystal from Sri Lanka. 88.8 ct. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

What makes a sapphire world class? Similar to ruby, a top specimen should be of fine color and good shape (not foreshortened or flattened, although there are always exceptions). It should also be large enough in size (2 cm or more) and not too water-worn. As I mentioned before external surfaces are extremely important in mineral specimens.

Due to the higher value of cut stones versus specimens, most Sri Lanka and Mogok gem crystals have been cut. However the gap has narrowed somewhat over the past two decades.

Outside of Sri Lanka and Burma, there are a few other notable localities. Most places that produce ruby also produce sapphire crystals; however the overwhelming majority would not be considered beautiful. There are exceptionally fine gem blue sapphires found in Yogo, Montana, but the largest ever found was only three grams.

FURTHER THOUGHTS

A while back I received some comments from an advanced collector who was contemplating a ruby crystal purchase. He asked fellow collectors and dealers if they had a ruby in their collection and, if not, why.

Answers were almost universally that they didn’t have a ruby. The reasons were generally because “I can’t find one on matrix” or because “I don’t find them attractive or aesthetic.” Generally the answers were something to the effect of: “I wouldn’t want a ruby in my collection.”

My response was twofold. First, there is no accounting for individual taste. I’ve always advised collectors to collect for themselves. In other words, buy what you find attractive.

But I find the main reason most collectors have no fine ruby or sapphire in their collections is rarity. Beautiful specimens are simply too scarce. As I’ve said, a fine red is almost impossible outside of Mogok, Burma (and a few select pieces from Luc Yen). The few lucky collectors who have fine rubies love them. Most collectors have never seen a truly fine ruby specimen. The same goes for sapphire crystals.

MUSEUM COLLECTIONS AND BEYOND

Allow me to close with another story. When Paul Desautels (former curator of the Smithsonian Institution’s mineral department) joined the Houston Museum of Natural Science as curator, his first move was to ensure that the collection would include a fine Mogok ruby. This was so important to him that, before agreeing to accept the position, he set up an exchange for a duplicate from the Smithsonian collection. That’s how significant a fine ruby specimen was. No ruby, no Paul.

Only a few museums have beautiful ruby or sapphire specimens. One revered example is found in the British Museum. The most famous crystal in the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History is the Hixon ruby from Mogok.

All gem connoisseurs know ruby is the king of gems. Perhaps with some of the wonderful crystals presented in this book, more collectors will be educated to understand and appreciate the beauty and tremendous rarity of natural ruby and sapphire crystal specimens. And in doing so, it is my hope that we might manage to save some of the best examples from the lapidary’s wheel. For when it comes to artists, I believe Mother Nature is the greatest that has ever lived.

REFERENCES

Thompson, W. (2007) Ikons: Classics and Contemporary Masterpieces. Tucson, AZ, Mineralogical Record, published as supplement to the Mineralogical Record, Vol. 38, No. 1, Jan.–Feb. 2007, 192 pp.

EDITOR’S NOTE

Over a career that has spanned more than six decades, William Larson has become a legend in the field. As a mineral and gem dealer, he has placed specimens in the planet’s greatest collections, both public and private. In addition to his personal world-class mineral (and gem) collection, he also owns one of the finest libraries of books relating to minerals and gems.