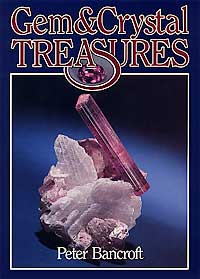

Lapis Lazuli from Afghanistan by Peter Bancroft

Sar-e-Sang Mine, Jurm, Afghanistan

Editor’s Note: We are pleased to reprint this selection from Peter Bancroft’s classic book, Gem and Crystal Treasures (1984) Western Enterprises/Mineralogical Record, Fallbrook, CA, 488 pp.

|

Royal blue lapis lazuli, the gem variety of lazurite and one of the most beautiful opaque gemstones, is a sodium and aluminum mineral of considerable complexity. Known as “sapphires” by the ancients, the stone occurs in only a few major deposits around the world, notably Lake Baikal in Siberia, Ocalle

The ancient royal Sumerian tombs of Ur, located near the Euphrates River in lower Iraq, contained more than 6000 beautifully executed lapis lazuli statuettes of birds, deer, and rodents as well as dishes, beads, and cylinder seals. These carved artifacts undoubtedly came from material mined in northern Afghanistan. Later Egyptian burial sites dating before 3000 B.C. contained thousands of jewelry items, many of lapis. Powdered lapis was favored by Egyptian ladies as a cosmetic eye shadow and in later years it was used as a pigment for ultramarine paints. Pliny the Elder described the stone as “a fragment of the starry firmament.”

The most prized lapis is a dark, nearly blackish blue, much deeper than turquoise and more intense than sodalite or azurite. Lazurite occurs most frequently in lighter shades commonly mixed with streaks of calcite. Although attractive, this material is less desirable and consequently fetches a lower price. Pyrite, a commonly associated mineral, is often liberally sprinkled throughout lapis specimens, to create a striking combination of rich blue and brassy gold.

| Lapis lazuli Size: 9 by 6 cm Locality: Sar-e-Sang Collection: Private collection Photo: Harold and Erica Van Pelt |

|

The route to the lapis mines in the Kokcha Valley is long, tortuous, and dangerous. From Feysbad, capital of Afghanistan’s northeast province of Badakhshan, a poor road stretches southward through tiny hamlets of mud-walled huts standing on uneven ground wracked by the earthquake of 1832. After motoring as far as Hazarat-Said, the traveler must spend another full day on horseback before reaching Kokcha Valley. The small Kokcha River is the eastern tributary of the River Oxus which Marco Polo traversed and wrote: “There is a mountain in that region where the finest azure [lapis lazuli] in the world is found. It appears in veins like silver streaks.”

|

| Map of Afghanistan showing the location of the lapis lazuli mines. (Illustration ©Richard Hughes) |

The lapis is mined on the steep sides of a long narrow defile sometimes only 200 meters wide and backed by jagged peaks that rise above 6000 meters. Sparsely populated and covered with snow for much of the year the barren region is inhabited by wild hogs and wolves. The summer sun is scorching, but temperatures drop below freezing at night. British Army Lieutenant John Wood reached the lapis mines for the East India Company in 1837, and wrote in his Journey to the Source of the River Oxus, “If you do not wish to die, avoid the Valley of Kokcha.” This is surely not one of the world’s better sites for a field trip!

|

| Pack train in high, desolate

and very cold Kokcha Valley. Photo: Pierre Bariand |

Darreh-Zu, one of the oldest mines along the Kokcha, is now closed and presumably exhausted. The nearby and relatively new Sar-e-Sang mine currently yields substantial amounts of good quality gem material and has produced rare 5-centimeter lazurite crystals. The largest found thus far, a well formed dodecahedron imbedded in calcite, was collected in 1964 by Pierre Bariand, mineral collection curator at The Sorbonne.

Lazurite gem deposits occur in white and black marbles hundreds of meters thick. The gem veins, seldom exceeding 10 meters in length, lie in snow-white calcite. Associated minerals include pyrite, diopside, sodalite, forsterite, phlogopite, garnet, dolomite, apatite, and afghanite, a relatively new species of the cancrinite group. Gem lazurite is found in three Persian color classifications: nili (dark blue), assemani (light blue), and sabz (green).

|

| The Sar-e-Sang is high on a cliff but has produced the largest lapis lazuli crystals of all time. Photo: Pierre Bariand |

During the 1880s and early 1900s, lazurite was mined by the “fire-set” method: large fires were kindled at the tunnel face and then quenched with water. The sudden cooling caused face rocks to shatter, simplifying removal of the ore. The gem material was then cobbed away from its matrix. A critical shortage of wood and the availability of explosives eventually rendered the technique obsolete.

Many leading museums feature carvings and jewelry fashioned from Kokcha lapis. But nowhere is the gem more lavishly displayed than in Leningrad’s Hermitage Museum, where deep-blue figurines and vases stand 2 meters high.

The Sar-e-Sang mine has reserves of high-grade lapis lazuli and possibly more of the very rare lapis crystals. But political instability in Afghanistan clouds the future for both mining and distribution of the noble blue gem.

|

| Lazurite crystal in marble self-collected

by Pierre Bariand. Size of crystal: 5 cm; Locality: Sar-e-Sang Collection: Faculty of Sciences (Sorbonne) Photo: Nelly Bariand |

|

| Visiting party at entrance to

the Sar-e-Sang. Photo: Pierre Bariand |

|

| Tailings of the Darreh-Zu mine. Photo: Pierre Bariand |

|

| Portal of the Darreh-Zu mine, now exhausted. Photo: Pierre Bariand |

|

Palagems.com Lapis Lazuli Buying Guide Introduction. Lapis lazuli is one of the oldest of all gems, with a history stretching back some 7000 years or more. This mineral is important not just as a gem, but also as a pigment, for ultramarine is produced from crushed lapis lazuli (this is why old paintings using ultramarine for their blue pigments never fade). Color. For lapis lazuli, the finest color will be an even, intense blue, lightly dusted with small flecks of golden pyrite. There should be no white calcite veins visible to the naked eye and the pyrite should be small in size. This is because the inclusion of pyrite often produces discoloration at the edges which is not so attractive. Stones which contain too much calcite or pyrite are not as valuable. Clarity. Lapis lazuli is essentially opaque to the naked eye. However, fine stones should possess no cracks which might lower durability. Cut. Lapis lazuli is cut similar to other ornamental stones. Cabochons are common, as are flat polished slabs and beads. Carvings and figurines are also common. Prices. Lapis lazuli is not an expensive stone, but truly fine material is still rare. Lower grades may sell for less than $1 per carat, while the superfine material may reach $100–150/ct. or more at retail. Stone Sizes. Lapis lazuli may occur in multi-kilogram sized pieces, but top-grade lapis of even 10–20 carats cut is rare. Name. The name lapis means stone. Lazuli is derived from the Persian lazhward, meaning blue. This is also the root of our word, azure. Sources. The original locality for lapis lazuli is the Sar-e-Sang deposit in Afghanistan’s remote Badakhshan district. This mine is one of the oldest in the world, producing continuously for over 7000 years. While other deposits of lapis are known, none are of importance when compared with Afghanistan. Lapis lazuli is also found in Chile, where the material is heavily mottled with calcite. Small amounts are also mined in Colorado, near Lake Baikal in Siberia, and in Burma’s Mogok Stone Tract. Enhancements. The most common enhancement for lapis lazuli is dying (staining), where a stone with white calcite inclusions is stained blue to improve the color. Other enhancements commonly seen are waxing and resin impregnations, again, to improve color. The color of stained lapis is unstable and will fade with time. As with all precious stones, it is a good practice to have any major purchases tested by a reputable gem lab, such as the GIA or AGTA, to determine if a gem is enhanced. Imitations. Sintered synthetic blue spinel was once used as an imitation of lapis lazuli, but is rarely seen today. So-called synthetic lapis lazuli (such as the Gilson product) is more properly termed an imitation, since it does not match exactly the structure and properties of the natural. It is found in various forms, complete with pyrite specks (but all lacking calcite). Various forms of glass and plastic are also commonly seen as lapis imitations.

Properties of Lapis Lazuli

|