Lloviznando Opal: A look above the surface

This gemstone was our featured stone for June 2008. We’re pleased to present here an extended look at this rare material from central Mexico.

|

| Rough and cut lloviznando opal. Cut: 22.47 carats, 18.97 x 18.3 x 11.97 mm. Rough: 31.66 carats, 35 x 30 x 7 mm. From the Gladnick Collection. These pieces have been sold. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

For in them you shall see the living fire of the ruby, the glorious purple of the amethyst, the sea-green of the emerald, all glittering together in an incredible mixture of light.

— Roman Pliny the Elder on Opal, 1st Century AD

In general when we hear “opal” we think Australia, but there are a few areas in Mexico that produce some of the finest opal with play-of-color on the planet. Although Mexican fire opals with orange-to-red body color are relatively common, other varieties from Mexico exhibit a dazzling play-of-color phenomenon. Some maintain the orange-to-red body color while a few take on a white or ice-blue base, which is often referred to as “water opal.” The singular body colors can be beautiful, but the exceptional ones also include another dimension of color. When all the components align, a full spectrum of color dances from within the heart of the gem and jumps out of the stone three-dimensionally, almost floating above the surface. The local Mexican miners called the light-and-color dance “floating light” or lloviznando.

|

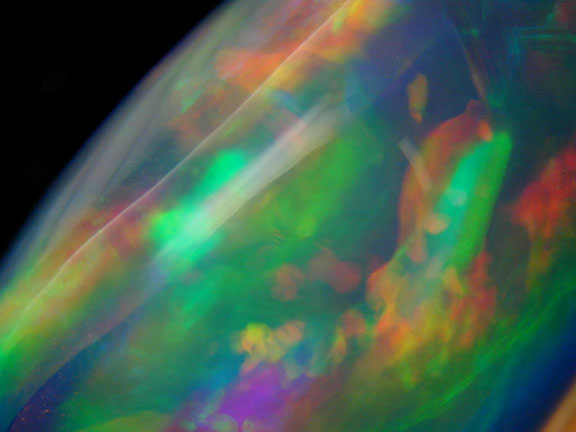

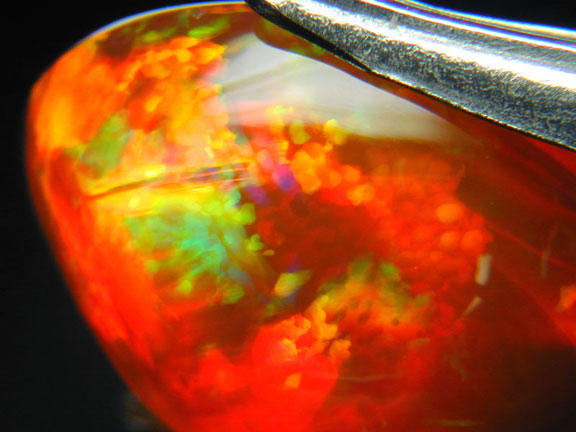

| Light rise over Planet Opal. A close-up view of the source of the color in this featured stone. From the Gladnick Collection. (Photos: Jason Stephenson) |

|

Our featured gemstone for June 2008 is by some standards one of the best from the Magdalena mining district in Jalisco, Mexico. A true spectacle of lloviznando: you can actually spin it around in your hands and interact with the play-of-color. A magical blend of optics and color in a tangible jewel. This 22.47-carat opal exhibits a icy-blue body with a play-of-color that meanders through all the shades of the rainbow. Each color a pure neon hue playing in formations like brush strokes and flowing bands.

|

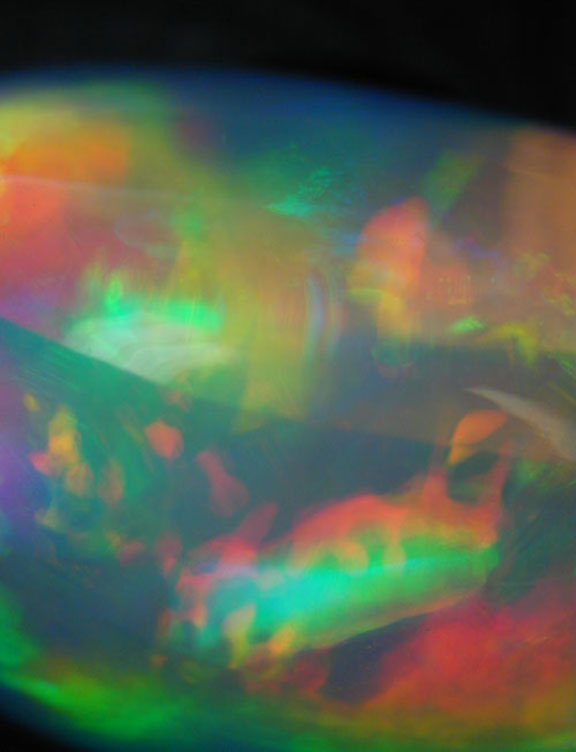

| “Colibrí,” the hummingbird. A 80.12-carat rough nodule from the death of the Iris Mine. Bill Larson Collection. (Photo: Nikolai Kouznetsov) |

The Geography of Mexican Opal

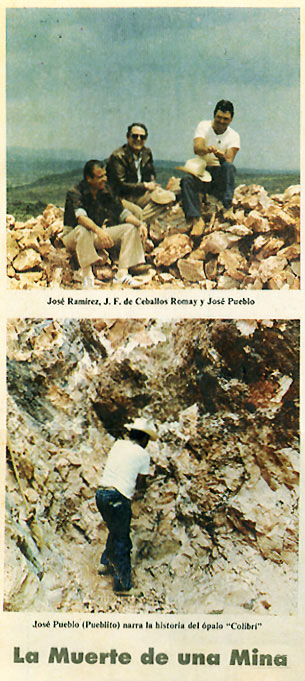

The two main mining areas in Mexico that produce these precious opals are Querétaro and Magdalena, situated in central Mexico, northwest of Mexico City and Guadalajara respectively. These historical deposits have been coveted by the native families for over a hundred years. They consistently produce oranges, reds, and blues with little or no play-of-color, while sporadically producing the wild, full-spectrum patterns of color seen in the rare opals. In August of 1984 a local newspaper in the Querétaro mining district declared La Muerte de una Mina: the death of the Iris Mine.

|

| The Death of a Mine. From the Mexican daily Excélsior, August 19, 1984, showing a local mining family and the tannish rhyolite that held the “Colibrí” (hummingbird) nodule. |

After many changes of ownership and a lack of funds, the final detonations at the Iris Mine were sparked and all but the rubble remains. They did, however, find the end-all-be-all jewel in the final blast, and the death of the mine ensued. They named the spectacular nodule “Colibrí,” or hummingbird. The Iris Mine might be dead, but the Querétaro and Magdalena mining districts roll on into the future. However, the miners say they are lucky to find a few truly spectacular opals over a year of mining.

|

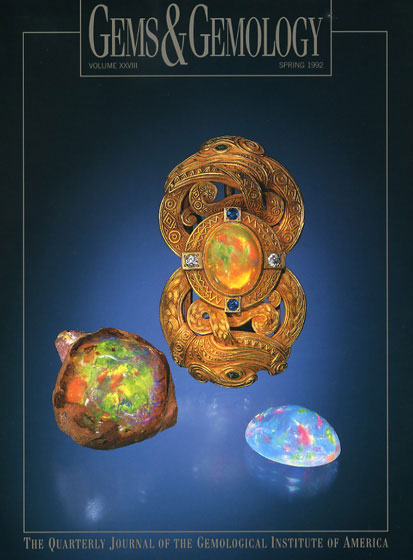

| Gems & Gemology (Spring 1992) cover featuring the “Hummingbird” (left) and a blue opal from Bill Larson’s collection. The blue, or “water” opal on the cover is very similar to this month’s feature—just a little smaller, at 16.27 carats. |

The Geology of Lloviznando

The opals crystallize in a hydrothermal system where the hydrous silica gels get trapped and concentrated in cavities and fractures within rhyolitic lava flows. This unique geologic process then “freezes” the opal melt from the high temperature solutions that begin at around 160°C. The opals often have one- and two-phase inclusions with trapped remnants of aqueous liquids, water vapor, carbon dioxide, and sodium chloride from the original solution. The Querétaro district is one of the only significant sources of gem-quality “fire” opal to originate from an igneous or rhyolitic source. The Magdalena district has a similar geology, producing exceptional fire opals and, in rare cases, “water” and lloviznando opals as well. Australian opals, on the other hand, form at low temperatures from circulating groundwater in sedimentary-type environments.

|

| Firestone. This is an exceptional example of the red body color with play-of-color. From the Magdalena mining district. (Photo: Jason Stephenson) |

Lloviznando is the gerund of the Spanish verb lloviznar, “to drizzle.” It is often spelled llovisnando by local Mexican miners and dealers, as well as other Spanish speakers. Other variant spellings appear in the literature, including the past participle, lloviznado.1 Frank Leechman, in The Opal Book, first published in 1961, used the related variant, lluviznados,

pronounced “you-vees-nah-doz”, and meaning fire-rain. In the high plateau of Mexico there are frequently very heavy showers during the rainy season. When the sun shines through such a slanting shower each rain droplet reflects its individual minute rainbow as a shaft of moving colour. The lluviznados have this character; shafts of colour, sometimes minute, sometimes bold, penetrate an almost transparent body of bluish or faint topaz opalescence with each movement of the stone. Its scattered specks of different colours gleam in a polished cabochon like swarms of tiny stars.2

The great John Sinkankas used the variant lluvisnando3 in his book Gemstones of North America (Volume 1, 1959), describing this Mexican opal par excellence as “to sprinkle with rain,” and stating that connoisseurs of opal agree that Mexican varieties possess a certain limpidity and play of color unique and distinguishable from any opal on the planet. Once you are familiar with the dazzling hues, fluidity, and structure of the phenomenal opals from Mexico you can identify the characteristic anywhere they happen to be displayed.

The fire and water opals of central Mexico have been seen and described dating back to the Aztecs, who called the play of color phenomenon vitzitziltecpatl or “hummingbird stone,” alluding to the flashes of color seen as the colorful little hummingbirds hover or float in the air.

Today, explanations and interpretations of the meaning of lloviznando by local miners and dealers vary, from a literal drizzling phenomenon, to the poetic “floating light.” As a local lover of lloviznando told us:

little raindrops barely there but still like in London when it seems to rain but it’s not really raining strongly; it’s just like [the] feather touch of rain… shining like raindrops; it’s amazing: the color, the shine, and the sparkles of stars in the stone.

And, again, Sinkankas (1959):

The body color is an extremely pale honey yellow, sometimes faintly blue, and exceptionally transparent; in the depths of each gem may be narrow sheets of intense color descending like a shower of rain drops through the rays of the setting sun. Sometimes the individual darts of flame are small, or other times very coarse, but in any case, once seen, a good lluvisnando is not easily forgotten. There are a few opal gems anywhere which can compare in beauty with the finest of the Mexican kinds.

The Future of Fire and Water

Pala has started a relationship with one of the the mining families from the Magdalena district to start selling opals, from small finer pieces to exceptional lloviznando varieties. So hopefully we will be able to offer a nice selection of fire and water opals with play-of-color. Lines of communication have also been started in regards to Pala actually offering our expertise in mining. The deposit has historically been an open pit, but there may be ways to go underground to chase the rich ore veins. The partnership could be a very interesting way to bring more spectacular fire opal to the American market and beyond.

Call or email us for information on Mexican opal.

- Colorado gem dealer Steve Green, who first raised with us the issue of variant spellings, consulted a colleague in the central highlands of Mexico who uses the term llovisnado (“drizzled”) to apply to such opal, “porque llovisnando es en el momento que está sucediendo” (“because drizzling is in the moment that it’s happening”). [back to text]

- Leechman includes this description in a section of the chapter “The Foreign Opal Fields” (p. 22) in which he quotes personal communication in 1957 from Ron Stokes of Vancouver. It’s possible this description was obtained from Stokes. [back to text]

- Leechman’s and Sinkankas’s rendering of the word as lluviznados and lluvisnando, respectively, may be due to the near-homonymic Spanish words lluvia (“rain”) and lluvioso/-osa (“rainy”). Others have used the lluvi- variant. Allan W. Eckert, in The World of Opals (1997, p. 170), writes about girasol opals: “in Mexico they are called Iluviznados”—the capital I being a typographical error that is repeated twice more (pp. 174, 227), but is rendered lluviznados twice in the index (p. 446). In Gems (6th ed., 2006), Michael O’Donoghue includes the term lluvisnando in the glossary (p. 831). [back to text]

This article was updated April 28, 2009.