Blue, green and red – sapphire, emerald and ruby – the colored-stone trinity. There is something primal about our attraction to these gems. Each relates to a familiar part of life. Blue is ocean/sky. Green – verdant soothing. And red? Red is fire, blood, the very life-giver itself – passion. Women do not paint their lips green, nor do men send their love blue valentines. No, for thoughts of love and passion, only one color will do – red. And no more passionate gem exists than the ruby.

That said, let us take a look at the beast known as ruby.

Building the perfect beast

Ruby is among the rarest of all the major precious stones, with only a handful of sources producing facet qualities in any commercial quantity. In analyzing this gem we must first realize the perfect ruby does not exist. Get it out of your head. With ruby, there are no tens. So rare is this lass that even an eight is worthy of down-on-your-knees idol worship.

Why that is so is because fine ruby requires chromium, and chromium, as it does in emerald and alexandrite, messes with the stone, breaks it up inside. Thus there are plenty of corundums with chromium, but only a rare few that grow slowly enough to achieve perfection.

The best rubies have high color saturation. This results from a mixture of the slightly bluish red body color and the purer red fluorescent emission.

Let it glow

Ruby’s red glow is like the snowflake and the rainbow. In one of those glorious accidents of nature, ruby is blessed with both a red body color and a tendency to take bits of visible blue and green light and blast them back with a laser-like red emission. Indeed, the first lasers made use of this very property (synthetic ruby is still a common laser material).

This red glow is key, for it tends to cover up the dark areas of the stone caused by extinction from cutting. Thai/Cambodian rubies might possess a purer red (less purple) body color, but they lack the strong fluorescence. These Fe-rich rubies display good color where light is properly reflected off pavilion facets (internal brilliance). However, where facets are cut too steep, light exits through the side instead of returning to the eye, creating darker areas (extinction).

All stones possess extinction to a certain degree, but in fine rubies, the strong crimson fluorescence masks it. The best Burmese stones actually glow red and appear as though Mother Nature brushed a broad swath of fluorescent red paint across the face of the stone. This is the carbuncle of the ancients, a term derived from the glowing embers of a fire. Indeed, the King of Ceylon was said to possess a ruby that shone so brightly that when he brought it out at night, it would light up the entire palace.

|

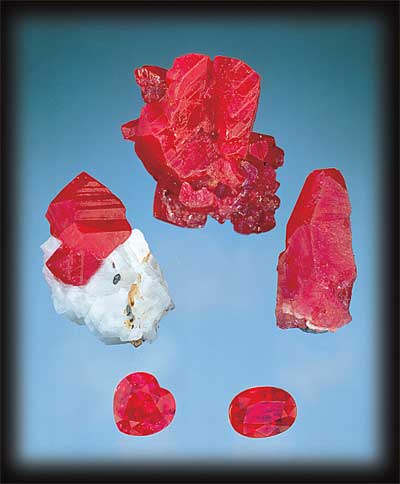

| Rough and cut rubies from Burma, Vietnam and Afghanistan Photo: Harold & Erica Van Pelt; Gems: Pala International |

Gossamer

What gods are these? Not only did they bless the ruby with an inborn glow to match its scarlet skin, but such was their benevolence that they also gave us silk – oriented needles of rutile – gossamer threads that banish the darkness besmirching the rest of the mortal gem world.

Such tiny exsolved inclusions scatter light onto facets that would otherwise be extinct (dark). This gives softness, as well as spreading it across a greater part of the gem’s face. Thai/Cambodian rubies contain no rutile silk, and thus possess more extinction.

In actuality, rubies from most sources possess a strong red fluorescence and silk similar to those from Burma, with the Thai/Cambodian rubies being the exception. However, those from Sri Lanka are generally too light in color, while, with other sources, such as Kenya, Pakistan and Afghanistan, material clean enough for faceting is rare. Thus the combination of fine color (body color plus fluorescence) and facetable material (i.e., internally clean) has put the Burmese ruby squarely atop the crimson crest. Indeed, some consider Burma to be not just the best source, but the only source of stones fit to be called ruby.

Seeing red

What do I look for in ruby? Bright is first and foremost. Can’t stand the dull or dark stuff. Not for me the burgundy reds typical of the Thai/Cambodian border. When I fill my tank, I want gasoline that burns.

Color

For ruby, the intensity of the red color is the primary factor in determining value. The ideal stone displays an intense, rich crimson without being too light or too dark. Stones which are too dark and garnety in appearance, or too light in color, are less highly valued. The finest rubies display a color similar to that of a red traffic light.

There is a tendency for the market to favor stones of the intense red-red color. Certainly the highest prices are paid for these. But do not overlook the slightly less intense shades. Such gems have a brightness missing in their more saturate brethren and often look better in the low lighting that one typically wears fine jewelry. Like beautiful women, rubies do come in many shades, the preference for which is a matter of personal taste. Ah, but isn’t that what makes life worth living?

Clarity

In terms of clarity, ruby tends to be more included than sapphire. While the general rule is to look for stones that are eye-clean, i.e., with no inclusions visible to the unaided eye, extremely fine silk throughout the stone can actually enhance the beauty of some rubies.

For star rubies, while a certain amount of silk is necessary to create the star effect, too much desaturates the color, making it appear grayish. This is undesirable.

Cut

In the market, rubies are found in a variety of shapes and cutting styles. Ovals are cushions are the most common, but rounds are also seen, as are other shapes, such as the heart or emerald cut. Slight premiums are paid for round stones, while slight discounts apply for pears and marquises. Stones that are overly deep or shallow should generally be avoided.

Cabochon-cut rubies are also common. This cut is used for star stones, or those not clean enough to facet. The best cabochons are reasonably transparent, with nice smooth domes and good symmetry. Avoid stones with too much excess weight below the girdle, unless they are priced accordingly.

Prices

With the exception of imperial jadeite and certain rare colors of diamond, ruby is the world’s most expensive gem. But like all gem materials, low-quality (i.e., non-gem quality) pieces may be available for a few dollars per carat. Such stones are generally not clean enough to facet. The highest price per carat ever paid for a ruby was Alan Caplan’s Ruby (‘Mogok Ruby’), a 15.97-ct. faceted stone that sold at Sotheby’s New York, Oct., 1988 for $3,630,000 ($227,301/ct).

Stone Sizes

Large rubies of quality are far more rare than large sapphires of equal quality. Indeed, any untreated ruby of quality above two carats is a rare stone; untreated rubies of fine quality above five carats are world-class pieces.

Quality ranking of rubies by country

An approximate ranking of important ruby origins is given below. This applies only for the finest untreated qualities from each source and is but a general approximation. In other words, a top-quality Thai/Cambodian ruby can be worth far more than a poor Mogok stone.

- Mogok, Burma

- Sri Lanka

- Madagascar

- Nanyazeik, Burma

- Everything else

Mogok

When we talk ruby, we talk Burma. For connoisseurs, no other will do. In the days of yore, matters were simple. Burma meant Mogok. This storied deposit was known for over 1000 years as the home of the finest ruby on the planet.

While Mogok is the traditional source of the world’s finest rubies, good stones are rare even from this fabled area. Pigeon’s blood was the term used to describe the finest Mogok stones, but has little meaning today, as so few people have seen this bird’s blood.

Mogok-type rubies possess not just red body color, but, by a freak of nature, red fluorescence, too. In addition, the best stones contain tiny amounts of light-scattering rutile silk. It is this combination of features that gives these rubies their incomparable crimson glow. In Mogok rubies, the color often occurs in rich patches and swirls, and color zoning can occasionally be a problem. The shape of Mogok ruby rough generally yields well-proportioned stones.

In addition to faceted stones, the Mogok Stone Tract also produces the world’s finest star rubies.

Möng Hsu

When the Möng Hsu deposit came on stream in 1992–93, it took the ruby world by the storm. Suddenly, we were awash in a sea of red the likes of which had never been seen before. And fine stone it was, too. This was not the garnet-like hue of Thailand, but a rich, fluorescent red.

In 1992, the Möng Hsu (Maing Hsu) deposit in Burma’s Shan State began producing good material. This has continued to the present, so much so that close to 90% of the fine cab and facet-grade ruby in the world market is from this deposit. But most cut stones are under two carats.

Möng Hsu material can be extremely fine, but virtually all is heat treated, and most is also flux-healed.

Nanyazeik (Nayazeik)

In the past year or so, rubies have started to come out of Nanyazeik in Burma’s Kachin State. I did see one fine purplish red piece from this deposit on my last trip to Burma in June, 2001. Only time will tell whether Nanyazeik has the makings of an important source. Other than ruby, Nanyazeik has produced some super red spinels, equal to anything from Mogok.

Sri Lanka (Ceylon)

The classic case of giving a dog a bad name. Some of the world’s finest rubies have come from Sri Lanka’s gem gravels, but because of the erroneous “pink sapphire” moniker, they have been largely overlooked. Top-grade Sri Lankan reds are virtually indistinguishable from their Mogok brethren, but most tend towards purple or pink. As with Sri Lanka sapphires, color accumulates in large stones and so they can be quite magnificent in sizes of five carats or more. Due to the bipyramidal shape of the rough, many stones are cut with overly deep pavilions. Sri Lankan ruby is strongly fluorescent and stars are common.

Madagascar

When I was teaching gemology in Bangkok, I used to point to an island off the coast of Africa and inform my students that, if they wanted to hunt gems, this would be a great place to start. Known in olden times as the “Beryl Island,” Madagascar was long considered mineralogical nirvana. And today, it is equally known for its gem wealth.

Prior to this year, Madagascar produced mainly fine blue sapphires and pinks. But now two important ruby deposits have been discovered. The first is about 10–30 km. inland from the coastal town of Vatomandry, while the second is roughly 45–70 km. from the town of Andilamena. Vatomandry is said to produce the better-quality stone, being lighter and brighter (more reminiscent of Burma), while the Andilamena stone is somewhat darker and not as clean. Rutile silk seen in some pieces suggests that star stones may be forthcoming. Much of the material from both deposits is heat-treated.

It is still too early to properly rank Madagascar in the ruby world, but the stones I have seen so far suggest that there is great promise.

Vietnam

Beginning in the late-1980’s, fine ruby began pouring out of two different deposits in Vietnam. Although Vietnam’s ruby originates from two different mining areas, Luc Yen (north of Hanoi) and Quy Chau (south of Hanoi), both sources display similar characteristics.

There’s nothing like time to put things in perspective. In the late 1980’s, Vietnamese ruby literally exploded on the world gem market. The best Vietnamese ruby approaches fine Mogok, but since the early 1990’s most have tended towards pink. Today, little facet-quality is produced, and even the cabochon material rarely competes with that available from Möng Hsu. Some pinkish star material is also produced.

Kenya & Tanzania

Stones from these sources are magnificent when clean, but facet-grade material is rare. Like Burma, much of this material is strongly fluorescent. Star stones are not produced from these deposits.

One specific deposit is worth mentioning. Beginning in the mid-1990’s, mines near Songea began to produce material with a dark, garnety color veering towards orange. While this material is ruby of a sort, it is marginal due to its high Fe content.

Afghanistan

Jagdalek has produced rubies that rank with fine Mogok stones, but facetable material is in short supply. Similar to Vietnamese rubies, many of these stones contain small areas of blue color. They are also strongly fluorescent, and if the deposit ever produces clean material, watch out. No star stones here.

Thailand/Cambodia

This material’s main attribute is its high clarity, but the flat crystal shapes generally yield overly shallow stones. Due to the high iron content, which quenches fluorescence, most stones tend to have a garnet-red color. An additional problem is the total lack of light-scattering silk inclusions (star stones are not found). Although heat treatment does make improvements, it is not enough. In Thai/Cambodian rubies, only those facets where light is totally internally reflected will be a rich red; the others appear blackish, as with red garnets. Thai stones are actually less purple than most Burmese rubies. However, Burma-type rubies appear red all over the stone. Not only is a rich red seen in the areas where total internal reflection occurs, but due to the red fluorescence and light-scattering silk, other facets are also red.

With the decline in Burma production during the 1962–1990 period, the market became conditioned to Thai/Cambodian rubies, with some people actually tending to prefer them (in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king). Thai/Cambodian rubies are acceptable only when good material from the Burma-type sources is not available. Today, production from the Thai side of the border is zero, and that from Cambodia is negligible. One occasionally hears statements about how Cambodian stones are superior to those from across the border in Thailand. This is untrue. The deposits are essentially one, directly straddling the border.

Buying considerations

Lighting

Proper lighting is crucial with any colored stone, but it is particularly important with ruby. The culprit is the fluorescent tubes so much a part of the modern office.

Most fluorescent tubes are so red-deficient that what they do to the color of a ruby should be outlawed. The reason is not hard to fathom. Ruby requires a light source with at least some red in it, and fluorescent tubes ain’t got none. Thus to bring out the inherent beauty in your stones, use halogen or incandescent bulbs, or natural skylight.

When using skylight (not direct sunlight) to view gems, keep in mind that red stones will appear best around noon, while blue stones look their finest just after sunup and just before dusk. So the rule is, if buying with natural light (skylight), don’t buy rubies (or red spinels) in the middle of the day.

Background checks

A word should also be said about the viewing background. At mining areas in Burma and elsewhere, rubies will often be sold on brass plates, yellow table tops or in stone papers with yellow liners (flutes). This makes the purplish red color more reddish. Place your stones on a white background for accurate color assessment.

Parcels

Buying parcels is a specialized area beyond the scope of this article, but I do want to mention that parcels often look great with all the gems piled together. This is because they draw color from one another, with each gem adding color to the whole. For an accurate assessment of color, spread the parcel out such that individual gems do not influence the color of those nearby.

Treatments

Ruby was one of the first gems to be treated, with reports detailing the heat treatment in Sri Lanka dating back over 1000 years. But today’s treatments are far more sophisticated than the primitive heatings of years gone by.

Today, ruby heat treatments run the gamut. The simplest is heating to knock out the blue component that makes a stone purplish. Such heating can be done at lower temperatures (say 700–1200 °C) and is often undetectable.

Another type involves heating to higher temperatures (1200–1800 °C) to remove rutile silk, and this is generally detectable.

But the type of heating that is most controversial is that applied to Möng Hsu rubies. This involves heating (1200–1800 °C) in the presence of a flux. The flux produces healing of surface-reaching fractures and openings. Thus a highly fractured stone can be healed and the fractures dissipated. [For more on this, see ‘Foreign Affairs’]

A further treatment occasionally seen is oiling/staining. Gentle heating in alcohol (be careful!) can generally remove oils/stains.

One of the true tragedies of gemstone enhancements is that they raise expectations among the gem-buying public to unreasonable levels. Once a customer has seen the shocking reds produced by human tampering, it becomes far more difficult to accept the more ordinary hues of nature. No where is this more true than with Möng Hsu ruby.

I will not go into enhancement ethics. But it is essential that both buyers and sellers are aware of the presence of any treatment, for they can have an important impact on value. It is my personal opinion that, when spending a significant sum of money on a ruby, one should avoid treated stones of any kind.

Bring it on home

Blue & green, sapphire & emerald – two legs of the colored-stone trinity. And what of red? Red is the most corrupting of colors and ruby the most wicked of gems, the very symbol of desire. Red is fire, blood, the very life-giver itself – passion. If this bothers you, then please shirk the scarlet stone.

A fine gem is a sexual being. It lives, pulses, throbs in a way that only those who have given themselves over to pure desire can understand. In each of us, there is a beast waiting to appear. We do what we can to suppress it, but it lays dormant, ever watchful for its moment. Ruby – that most sexual of precious stones – brings out the beast in me. Long ago I surrendered myself to her flesh. And now – having experienced those sensuous kisses and passionate nibbles – no other lover will do.

• • • • •

For additional information on ruby, see the following:

- Buyer’s Guide to Ruby by Richard W. Hughes

- Fire-Hearted Pebbles from Burma by C.M. Enriquez

About the author. Richard Hughes is the author of the classic Ruby & Sapphire, and is ex-webmaster of Palagems.com. He can be contacted at: rubydick@ruby-sapphire.com, or through his own web site, www.ruby-sapphire.com.

Author’s Afterword. Published in The Guide (2001, Vol. 20, No. 6, Part 1, November–December, pp. 4–7, 16).