Uncle Sam’s Oversight

By Elliott Flower

The following article was published in the July 1906 edition of Technical World Magazine (in 1923 becoming Popular Mechanics).

Note from Pala International editor: This article is offered in the Pala Presents series of reprints for its description of gemstone prospecting and mining in Baja California in the early 20th century. On the way to that destination, the reader will encounter author Elliott Flower’s breezy characterization of the spoils of the Mexican-American War as Uncle Sam’s “little settlement” as well as his allusion to that most infamous of images—the “sleeping Mexican”—and more. We could say that Flowers was a product of his time, but that characterization has to be reconciled with the purpose of his article—to dispel a stereotype, i.e., the image of Baja as being nothing more than a pile of rocks. “Topographically and climatically, this 600-mile peninsula is said to resemble Italy more nearly than any other place on the map of the world.” That’s some makeover. Oh, and, yes, it has “rocks.”

|

When Uncle Sam had his little settlement with Mexico, out of which he derived considerable southwestern territory, he generously allowed Mexico to retain a pile of rocks for which he thought he could have no particular use, this particular rock-pile being known as Baja (Lower) California. There seems to have been no reason why he should not have had these rocks, except that he did not want them. So he drew a line from the junction of the Colorado and the Gila rivers, straight across to the most convenient point on the coast, and decided that Mexico might retain what lay south of that line.

While this is history, it is just as well not to recall it when you happen to be in Lower California. The Mexicans do not like to be reminded of the fact that Uncle Sam got the territory to the north, and the Americans do not like to be reminded that they overlooked the value of what lay to the south. For, in Lower California to-day, there is no man so poor that he may not have a pleasant, plausible dream of wealth. Indeed, it is quite probable that, had the Mexican dreamed less, he would now have more of the wealth within his grasp. As for the American, he is after the wealth in his own strenuous way, tempered somewhat by climatic conditions; but he feels that he would have a much better chance under Uncle Sam’s beneficent rule.

And no doubt he is right. One cannot be in the country very long without feeling that its development has been retarded by Mexican rule—not so much the restrictions of Mexican rule, perhaps, as the lack of facilities and encouragement for the work of developing it: there is nothing progressive, no effort on the part of the Government to assist in the exploitation of its resources. So the Americans who have interests there—and Americans are largely connected with the more important and progressive enterprises—never cease to regret Uncle Sam’s oversight.

|

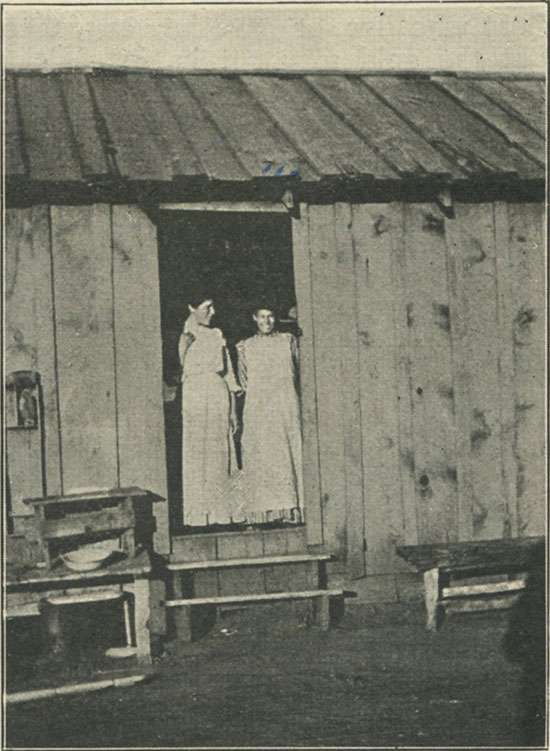

| A Mountain Miner’s Cabin in Lower California. Home of Señor Roderiquez—an unusually good building for the locality, as cut lumber has to be freighted over the mountains. |

Possibly, if you saw valleys on the other side of the line which, with no greater natural advantages than those of Lower California, were made surely profitable by irrigation, you would be disposed to grumble, also. A good irrigation system requires co-operation, a large investment of capital, and sometimes government aid and encouragement—which serves to explain why Lower California lags behind. The climate and the soil are excellent. Topographically and climatically, this 600-mile peninsula is said to resemble Italy more nearly than any other place on the map of the world. Beginning in the mountains, 5,000 to 10,000 feet above sea-level, there is a gradual slope to the Pacific coast which gives almost any desired climatic conditions except extreme cold. On the Gulf side the descent is rugged and abrupt.

|

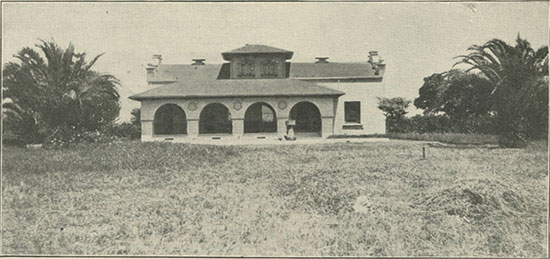

| On Uncle Sam’s side of the line. |

Very likely you have fallen into the error that Uncle Sam made in the long ago, and think of Lower California, when you think of it at all, as a barren waste of rock mountains. This is quite excusable, for the country has suffered much from reaction after over-booming. Men were first lured there by those fabulous tales that have done so much harm to other localities where gems and gold have been found: they were given false ideas of conditions, and they went improperly prepared. This world nowhere provides the reality that would equal the expectations of those early colonists and adventurers; and, in their disappointment, they gave Lower California an evil name that kept people away from it for many years. It produced nothing but rock, sage, rattlesnakes, and tarantulas, they said, and might be swallowed up by the sea without involving any loss to humanity. It naturally followed that people forgot about it and left it to the Indians; and it has taken many years to discover that the Indians have something that is too good for them to appreciate.

|

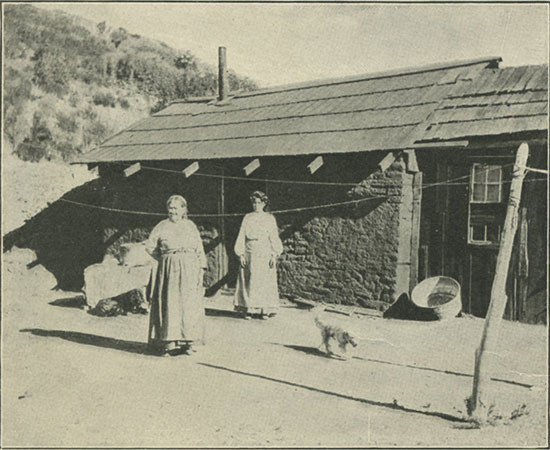

| On the Mexican side of the line. |

As a matter of fact, Lower California produces about all the varieties of cereals and fruits that are produced by southern California, and some that its northern neighbor cannot raise. There are dates, oranges, lemons, pineapples, bananas, peaches, quinces, plums, apples, pears, melons, figs, grapes, and cocoanuts. Furthermore, the same care and cash expenditure that has made of southern California a fruit country would do as much, or more, for Lower California. It needs the irrigation that has done so much in Uncle Sam’s country. Without that, it cannot produce the fruit in sufficient quantities to cut any figure in the market; but, without that, southern California would be shipping no fruit at all. The natural conditions are about the same. You may see, on one side of the boundary, a ranch that is a delight to the eye and that is sending its carloads of fruit to the eastern market, and, only a few miles away, a ranch that is forlorn, desolate, and unprofitable. The one is irrigated and the other is not.

|

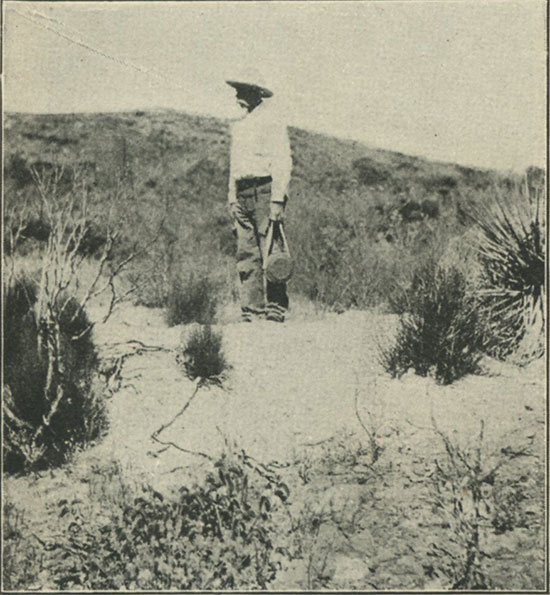

| Prospecting for gems in Lower California. (Click to enlarge) |

The conditions compel many of the people on the Mexican side of the line to give to cattle land which, with irrigation, could be much more profitably used in other ways. Even then, they are at a great disadvantage. Owing to the lack of transportation facilities, the cattle cannot be fattened at home, but must be driven to Imperial, across the line, for that purpose. To drive them such a distance after they are ready for the market is naturally out of the question; so Imperial takes them and ships them along when they are ready for the butcher, and you, who possibly get one of the steaks, probably have an idea that a cow could not live in Lower California. There is cheese, also, as a result of this cattle-raising; and that brings up another penalty of Uncle Sam’s oversight.

|

| Where gems are found. A characteristic landscape in Lower California. |

The United States is the natural market for nearly all the products of Lower California. But the tariff intervenes. The important ports, especially of the upper half of the peninsula, are on the Pacific coast side. The east coast is the more rugged, barren, and precipitous part; and, at the northern end, the Colorado Desert lies between Lower California and the rest of Mexico. So the natural market is to the north, where Uncle Sam rules and imposes duties. In the matter of cheese, by way of example, the duty is practically prohibitive; and men within a few miles of the United States have to freight their cheese by wagon long distances through the mountains to Ensenada. And the same is true of many other things.

|

| Mountain girls at cabin door. |

As for irrigation, which would permit much of this land to be used in more profitable ways, the natural conditions are extremely favorable. There is plenty of rain; but, unfortunately, it is not properly spread over the year. The mountains give ample opportunity for storing water at an altitude that would make it available; but, again, there is not the money to do the necessary work, and, in some localities, land-title uncertainties discourage investment. I passed through one valley, high in the mountains, above which there is a gorge that could be made into a splendid reservoir by the investment of a few thousands of dollars; but the money, even in that inviting instance, is not available, so the land is used principally for grazing when it is used at all. At the same time, there are ranches, near the coast, upon which the various fruits are successfully raised; and the people confidently believe that the conditions and encouragement to make this generally possible will come later. They have only to note what has been done on the other side of the boundary, to realize that this is no impossible dream—merely something that has been delayed by an arbitrary line drawn from the junction of the Colorado and Gila rivers to the nearest convenient point on the Pacific coast.

|

| A mountain ranch house. |

However, it is unnecessary to rely upon prospective irrigation for dreams: there is something much nearer and more dazzling. Possibly, if you were where you could find gold in the sand that you scooped up in your two hands, you also would indulge in dreams. You might go about the realization of those dreams in a little different way; but that is largely a matter of temperament. Possibly, if you found a gem of value among the loose stones and broken rock of a barren mountain (as I did at Jasay), you would begin to understand the optimism of those who live, or have interests, there. But the gold may not be in sufficient quantities to be taken profitably without a large preliminary investment in machinery, and most of the gems so easily found are likely to be fractured and unmarketable. Therein would seem to lie much of the fascination of the quest: you have your hand always almost upon the wealth that lies in the mountains, and you know that others have reached that wealth. It is there—gold, silver, many varieties of precious stones, copper, iron, tin, lead, mica. There are marble quarries and onyx quarries, and, on islands near the coast, salt deposits and pearl fisheries. Lower California gems are being shipped constantly to the London market. Knowing this, the finding of a few stones of value easily leads one to think that a fortune lies just a little ahead.

|

| A mountain stream in the dry season. |

My experience at Jasay gives a fair insight into, and understanding of, the dreams and disappointments of certain kinds of gem mining. The Jasay mines are owned by Eduardo Roderiquez, of Jasay, and Riall & Baldwin, of San Diego. I give Roderiquez first place in the combination, because he stays on the ground and sees to the actual work of mining; and a man who has to live as he does is certainly entitled to this slight honor. I went with Roderiquez from his cabin, something over 5,000 feet above sea-level, to his mines, a little higher up. It was all sage, sand, and rock here—desolate and unpromising—but I noticed that Roderiquez lagged a little, with his eyes on the ground, and occasionally picked up and examined pieces of stone and rock. Your true prospector is always prospecting. I followed his example; but, knowing nothing of precious stones, I picked up anything that had the color to catch my eye.

|

| Hessonite garnets from Baja California, Mexico. The three ovals total 4.63 cts and are part of seven stones in Inventory #1551. The round in the middle weighs 1.07 cts and is Inventory #1550. The round at bottom left weighs 1.60 cts and is part of Bill Larson’s personal Baja California collection. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

“What is it?” I asked, showing him a reddish stone.

“Hyacinth,” he answered quietly.

Now, the hyacinth may not be generally known in the East, except to lapidaries and jewelers; but it is listed among the precious stones, has a value of from $10 to $50 a carat, and there is a ready market for the uncut stones in London and Amsterdam. It ranks with the diamond in luster, and is next to the topaz in hardness. This I knew—and I had found one among the loose stones of the mountains.

“How much is it worth?” I asked.

“Nothing,” answered Roderiquez. “Air bubbles in it.”

|

| Tres Posos Valley Farm, Lower California, 3,000 feet above sea level. (Click to enlarge) |

In a minor way I was experiencing the sensations of the prospector, and I felt the tingle of the fever. That stone might be valueless, but the very fact that it was there at all seemed proof of the presence of stones that were not valueless. I certainly could not overlook such a chance to pick up money.

The next stone proved to be a hyacinth, also, but it had too many fractures to give a clear piece for cutting. Then I tried a stone of another color.

“Tourmaline,” explained Roderiquez. “Throw it away. I have picked up half a ton of them on one slope here, but I have yet to find one that is fit for the market.”

|

| Fit for the market. Blue-green tourmaline from the Delicias Mine in Valle del la Trinidad, Baja California, Mexico, 4.3 x 1.24 x 0.97 cm. (Photo: Mia Dixon; Collection: Bill Larson) |

And so it went on. There were surface indications of the presence of many kinds of precious stones; but, so far as perfect stones are concerned, the hyacinth alone has been reached at Jasay. I say “reached,” advisedly, for the mining here has been of the primitive kind, and very little has been reached that is not close to the surface. Indeed, it is difficult to go deep, for almost everywhere there are rock ledges to bar the way. But the point I wish to make is, that the profusion of these imperfect stones gives a basis for the dreams of future wealth. These surface stones, crushed and broken and chipped away from the formations with which they naturally belong, the result of some great natural upheaval, are in the nature of guide-posts. Somewhere near, it is reasoned, there must be the conditions that give the perfect stones; but that “somewhere near” is an elusive place, and it may be a very costly one to reach. It may be straight down, or it may be in almost any direction except up. But the search is a fascinating game, giving visions of fabulous wealth, and, meanwhile, there is enough to give encouragement.

|

| Señor Roderiquez at one of his mines. |

After I had found one stone that had a real market value, I wanted to keep right on hunting. To add to the allurement of surface indications, there is the knowledge that many varieties of gems are found and that the volcanic nature of the country will explain the presence of almost anything in this line. What you find near the surface is what has been forced up with the rocks; deep down there surely must be far finer specimens. There is also the record of success in other localities to urge one on. The zircon, jargoon, beryl, many varieties of the garnet group, turquoise, jasper, epidote, rose quartz, etc., are found, and—whisper it—a blue clay, said to be identical with the blue clay of the South African diamond fields.

|

| Un trío baja californiano. Clockwise from left, yellowish-green prehnite weighing 3.21 cts, sphene from Pino Solo weighing 3.61 cts and a trillion scheelite from the El Fenomeno Mine, Sierra Juares, Baja California, Mexico. (Photo: Mia Dixon; Collection: Bill Larson) |

“We’ll find diamonds here yet,” a prospector tells you confidentially; and one is inclined to think that the forces that have thrown up these mountains, tossing and grinding huge rocks, may have turned out almost anything in the process.

|

| An iron mine in the mountains, Lower California. |

Is there not enough in all this to feed the dreams of the average man? Many have “gone broke” in the search for wealth, but many others have prospered. Transportation is so difficult, except along the coast, that much is added to the expense of any operations; but, in the more accessible localities, wealth is coming out of many of the mines, and, near the coast, irrigation has been tried and has proved the promise of the soil. Practically, however, the surface of the country has been only scratched here and there.

|

| Cheese storehouse on ranch of Señor Roderiquez, Lower California. |

But, aside from the mineral and agricultural wealth, there are other opportunities for dreams. The true Lower Californian boasts of the climate as well as of the more tangible resources of the country. It may surprise those who have always associated it with torridity, but Ensenada feels sure of a future as a health and pleasure resort, and there are similar hopes and expectations all along the west coast from La Paz to Cape San Lucas. Ensenada already has a hotel overlooking the ocean, and boasts of tennis courts and golf links. The southern district, of which such great hopes are entertained; has nothing in the way of a pleasure resort hotel as yet; but you are assured that there will be one before long, and, meanwhile, “the Mexicans are a most hospitable people.” Possibly, however, your idea of a pleasurable outing does not involve boarding with a Mexican family. In that case you would better wait a little while before seeking resort pleasures south of Ensenada. Possibly, too, you have reasons for wishing to keep in touch with the rest of the world. In that case, even Ensenada might not prove satisfactory. It is the most easily and comfortably reached by steamer from San Diego, although the trip may be made by stage. Before it eclipses Coronado Beach (which is one of its dreams), there will have to be decidedly improved transportation facilities. This is conceded, and you are regretfully informed that they would have those facilities now if Uncle Sam had not overlooked the country. Later they will come, you are assured, and Ensenada will be a famous winter resort, from which all sorts of interesting excursions may be made. Lower California boasts of mud volcanoes; and there are medicinal springs and sulphur baths and pretty nearly everything in the natural freak line.

|

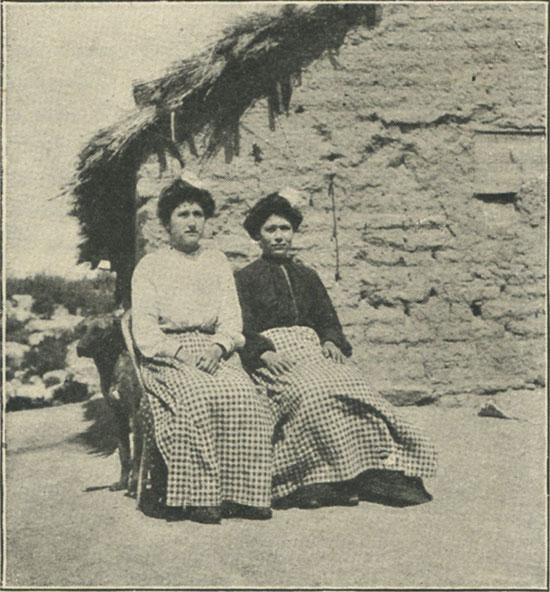

| Lower California belles. |

Development has been fairly rapid of recent years, largely owing to the efforts of the Lower California Development Company; but this company’s sphere of influence does not extend from the coast, and its boats make regular trips only about half way down the peninsula. Six trips a month are made to Ensenada, and two to St. Quentin, the onyx quarries, and Cedros Islands. This is all that the traffic now warrants; but, of course, the water transportation facilities will be increased as rapidly as there is need of it.

Back from the coast, there are only the stage lines, and even these reach comparatively few localities. There are mines of one sort or another everywhere; but only where exceptional success or the investment of money to do work on a large scale have brought together many people, do the stages come. The roads are difficult, and frequently great expense is involved in getting supplies and machinery necessary to do the work in any but the most primitive way. This unquestionably explains many of the failures. However, development is now progressing along sane, sober lines, in spite of the dreams, and the real wealth of the country will be uncovered gradually but surely. The opportunities are there; and, while Uncle Sam’s oversight has unquestionably retarded progress, his people are now doing the best they can under existing circumstances. They supply the energy that the native Mexican usually lacks, but the Mexican himself is likewise doing much for the country.