Venus in Bling: Bryan Ferry Allures, Offends, Endures

|

An Essay by David Hughes

News Editor, Pala International

Your editor recently re-viewed video compilations of musician Bryan Ferry and his band Roxy Music from 1973 through 1994. I was struck by the imagery and how it is mirrored in much of the Ferry/Roxy album artwork. It's awash in gemstones and jewelry (amongst other elements of fashion), in uncomfortably stale and meticulously staged images of women—deluxe if not delightful (to parody a song from the second Roxy album), especially when Ferry's appreciation for Third Reich representations is taken into account.

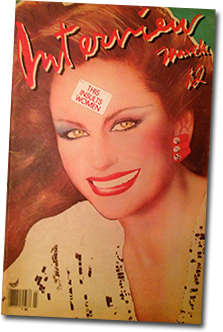

Ferry turns 70 next year, but rather than wait for that occasion to craft a critique of his superficial side, I'm doing it now. For the record (so to speak), I've been influenced by Ferry as much as by anyone else in the arts, but also have been ired by his employment of women as mute mannequins. Back in Roxy's heyday (their last studio album was released in 1982), one might be likely to pick up a copy of Andy Warhol's Interview magazine, as I did in early '81, vandalized by a "THIS INSULTS WOMEN" sticker. I wonder how many Roxy Music and Bryan Ferry albums received the same treatment…

In the essay that follows, I take a cursory look at Ferry's employment of the female form, and his use of gems and jewelry in the photography of his album covers and promotional videos. For those not familiar with his work, this will be an introduction to one of the most influential musical and representational stylists of the last forty years.

"Is it a boy or is it a girl?"

—Donovan Leitch, "Rules and Regulations"

|

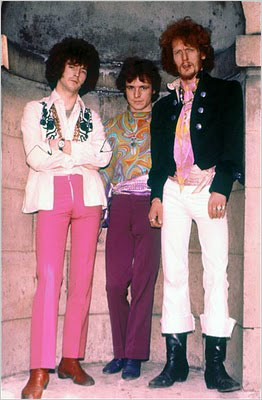

| March of the falsettos. Members of Cream, from left, Clapton, Bruce and Baker. Clapton happens to be wearing two necklaces. |

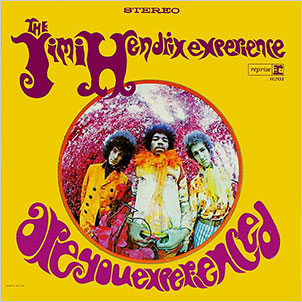

As a twelve-year-old my world was turned upside down by the gender bending of—not Glam artists T. Rex, David Bowie, or Slade—but Eric Clapton. In 1967, Clapton was in Cream, formed with bassist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker. I was at a church ski retreat in the mountains of Colorado when I heard the most exotic sound issuing from a portable record player. It was Cream's second album, Disraeli Gears. A fairly muscular blues had been softened by the falsetto/tenor of Clapton and Bruce on songs like "Strange Brew" and "We're Going Wrong," echoed elsewhere by the sustained fuzz-setto of Clapton's guitar. This was not the screeching of "Big Girls Don't Cry" from five years before; it was mellow and, frankly, feminine. The hand-tinted LP cover, with the trio rendered in fluorescent shades of fuchsia, amber and lemon, added to the mystery. In hindsight, the visual leap from psychedelia to Glitter and Glam wasn't a giant one, considering the flouncy aesthetic that already was in the air. Think Donovan's and Jimi Hendrix's penchant for ruffles and scarves; on the cover of Hendrix's first LP, Are You Experienced, he's wearing what looks to be a feather boa, a future trademark of Glam.

|

| Purple haze. Members of The Jimi Hendrix Experience, from left, Noel Redding, Hendrix and Mitch Mitchell. The U.S. version of this album, pictured above, was released at the end of the so-called Summer of Love, 1967. |

It would be four years after my hearing Disraeli Gears before what's known as Glitter and Glam finally flowered in the rock scene. And Bryan Ferry's band Roxy Music would be partly to blame for the phenomenon that caused parents alarm as their children donned dress-up and headed for the Sunset Strip and places like Rodney Bingenheimer's English Disco. Mick Rock and other photographers were there, documenting many of the principal figures. (For a discussion of the "unisex" phenomenon in fashion as well as the "peacock revolution" that stretched the envelope of male styles, see Jo B. Paoletti's Sex and Unisex.)

Re-Make/Re-Model

Bryan Ferry grew up in the working-class coal-mining town of Washington in the northeast of England. Although he identifies with the political Right, as explained by music biographer David Buckley, Ferry benefited "from the progressive socialist policies of grant-aided tertiary education." Rather than going into the pits, he studied fine art at Newcastle University. As a young man, he essentially reinvented himself, leaping "from pauper to prince," Buckley writes, "and leaving the burgher well alone." Earlier, Ferry shed what little regional accent he had. (It would have hampered him reading Shakespeare.) Having been in bands in school, Ferry moved to London, teaching art, amongst other jobs. When he was terminated, he auditioned as vocalist for prog-rockers King Crimson, but was turned down. And that's probably a good thing for music lovers.

Ferry took a DIY approach to writing music, and thus, as much as Roxy Music would be associated with Glam, Ferry's layman's methodology also would be adopted by Punk years hence. Ferry first worked with guitarist Graham Simpson, a fellow student at university at which time they'd formed an R&B outfit, the Gas Board, with John Porter, who would play bass on Roxy's second album. Roxy filled out with Andy Mackay, a reed player who had answered Ferry's ad for a pianist. Well, he did own a synthesizer, and later brought in Brian Eno to play it. Paul Thompson eventually became drummer, and Phil Manzanera guitarist, before they recorded their first album, Roxy Music.

|

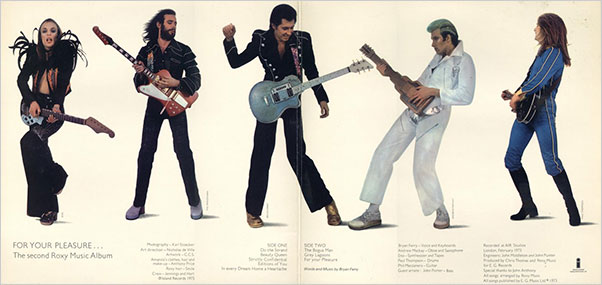

| Sophomore strut. Interior of the gatefold sleeve of For Your Pleasure. From left, Brian Eno, Ray Manzanera, Bryan Ferry, Andy Mackay and Paul Thompson. Here was the band in relatively austere attire, Eno's ostrich feathers and Mackay's silver lamé accents notwithstanding. Antony Price, who also collaborated on Roxy's album jackets, was the fashion designer. "I've never had any time for this theory that if you go out onstage wearing denims, you're for real," Ferry told journalist Charles Nicholl. Adding to the artifice: only Manzanera actually played guitar. |

The LP was enticing: from the crowd noise and tinkling glass that introduces "Re-Make/Re-Model," its odd chorus ("CPL5938," a license plate number and love object identifier) and its stop-start-stop-start extended ending quoting Duane Eddy as well as Richard Wagner, to the honky-tonk of "If There Is Something," to the Bogart tribute of "2 H.B.," to the dreamlike "The Bob (Medley)" with its combat sequence. It had the eclecticism of the Beatles and Procol Harum, but Manzanera's guitar work in many ways was bolder, razor sharp, Mackay's reeds fresher and refreshing, Eno's electronic effects cutting edge. By contrast, Ferry's voice was a throwback, a sort of baritone Rudy Vallée (they both covered the standard "As Time Goes By"). Everything old is new again, to quote Ferry's contemporary, the late Peter Allen. Both were fairly flamboyant performers, but where Allen's life was an open book via his music ("Is he or isn't he?" Allen would tease in his live show. "I am… Australian."), one would have to look a little closer, as noted below, to find Ferry the man reflected in his work.

Authenticity has been a theme often discussed by cultural critics, and Roxy music provides ample fodder for consideration. Philip Auslander, a professor who studies performance at Georgia Tech, writes that a performer's commitment to a particular style is evidence of the artist's sensibility; the more stable and consistent, the more genuine. Ferry and Roxy Music challenged this convention. Musically, a single song often would change course a time or three. The term "Medley" was applied in the case of "The Bob," but could have pertained to several other songs on Roxy Music. The live presentation of Roxy was itself a mélange of lamé galore, formalwear, spaceage togs and, eventually, keyboardist Bryan Eno's ostrich plumes and spangles. Yet the first album cover, 1972's Roxy Music, featured a photograph of model Kari-Ann Moller "dressed like an extra from Gone With The Wind," as Buckley writes, "where the band should have been." Rumors abounded that Moller actually was Ferry tarted up. As the late female impersonator Charles Pierce would say, it was going to be that kind of show.

|

| Star and cover star. Model Kari-Ann Moller, right, "was a great looking girl really," Bryan Ferry said last year, "in the tradition of Rita Hayworth." "These… were not pin-ups," writes Simon Frith and Howard Horne, "but comments on pin-ups." Perhaps Ferry was showing Sympathy for the Model? |

Lest one assume that gender ambiguity began with Glam, it's worth remembering an earlier craze just fifteen years prior (which could be considered the equivalent of three generations in the ever-changing world of pop music). Discussing the persona of Elvis Presley, cultural anthropologist Mary Bufwack and her journalist husband Robert Oermann write, "[R]ockabilly was more than a hard aggressive form of music. During its heyday, it was also often viewed as a violation of masculine standards of behavior." The quaver and cry in the voice, the vulnerability in the lyric, the sensuality of the long hair: hallmarks of androgyny.

Bitter-Sweet

—From the German stanza of "Bitter-Sweet," the

translation for which is credited to Constanze Karoli

and Eveline Grunwald, Country Life's cover stars

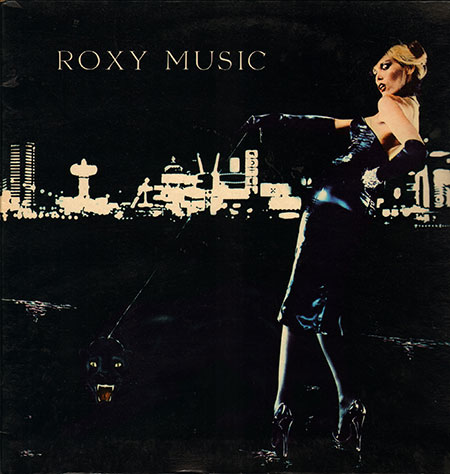

The album art of almost all the Roxy releases is striking in its portrayal of women in various stages of stress and undress. On the Roxy Music album jacket, model Moller (she later wed Mick Jagger's brother Chris) appears in an awkward position with a pained expression. The second Roxy cover star, the French multi-talented Amanda Lear (Ferry's then-consort), while accessorized with a sparkling diamond wrist cuff—the first of Ferry's images to feature such luxury goods—is perched on impossible pumps, teetering backwards, with a leashed panther, teeth bared (x2). The album's title, For Your Pleasure, is an ironic juxtaposition. As sociomusicologist Simon Frith and Howard Horne put it, Roxy's high fashion models were "photographed to draw attention to the discomfort of their pose."

|

| For whose pleasure? Cover star Amanda Lear walks (barely), with a black cat on one arm, a diamond cuff on the other. (Click for the full gatefold cover, including Ferry posing as a grinning limo driver.) Author David Buckley quotes Brian Eno as saying he personally would have preferred a straightforward image of the band on the cover. Then, somewhat contradictorily, "It's all becoming too stereotyped," he said, after only two years. Eno left Roxy after this album, his object being "to eliminate himself from his work…," according to Simon Frith and Howard Horne, "to cleanse his art of the idea of the individual artist"—the antithesis of Ferry-as-frontman. |

The sleeve of Stranded (1973), Roxy's third album, features another Ferry paramour, Marilyn Cole, literally decked out in ripped red chiffon, shipwrecked amid ferns and palms. This sort of imagery would become rampant in Los Angeles' fashion photography of the late '70s, with models' bodies bound if not gagged, knocked out if not knocked off, all smugly edgy in the wake of Punk's cultural barrage. The cover of Country Life (1974) isn't painful, merely titillating as it spoofs the British weekly of the same name, with Euro-models Constanze Karoli and Eveline Grunwald clad only in underwear, but in a rural setting. The album was censored in the Netherlands, of all countries, according to Wikipedia.

|

| Be brave, Ulysses. From the Siren photo shoot, model Jerry Hall surveils. Bryan Ferry spotted the perfect location on television. It's at South Stack on the northwest coast of the island of Anglesey, off the northwest coast of Wales. Much of the isle's coastlands have been designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in the UK. |

Model Jerry Hall is the Siren on Roxy's fifth album, issued in 1975. (Her two-year relationship with Ferry began the night of the photo shoot.) She is posed, if not poised, with arms akimbo, a human crab. Having obtained the booty of many a ship's hold, atop her tresses is a tiara with a single blue walnut-sized jewel; her arms are draped with milky-blue stones in grape-like clusters. Out of several images from the photo session floating on the Web, Ferry seems to have chosen the least flattering for the album. Writer Ian Penman, who once was slated to write Ferry's biography, has written an extended commentary on Woman's place in the singer's work. A taste: "She is constantly referred to, always there especially when absent: this is her virtue, her virtual nature. Which she is chiselled out of. A frozen asset." Earlier, Penman posits, "All [Ferry's] Songs' women… are voiceless sirens."

|

| Plastic people. Bejeweled mannequins dance the night away on the cover of a single from Manifesto. The duo would make a full-color comeback on the cover of the compilation The Early Years. |

Four years later, Roxy released Manifesto, the jacket featuring mannequins—female and male—festively and fashionably attired with pearls and other jewels, confetti flying. On the picture disk version of the album, the dummies were unclothed (but for their bling). Biographer Buckley quotes writer Chris Salewicz as saying that Ferry's affection for "arcane" affluence does not mark him as a social climber. He's simply drawn to the extraordinary, with a surrealist streak. Ferry's own website states that the imagery of Manifesto is a visual statement of one of his favorite themes: "the seductive beauty of artifice and the emotional void at the heart of the high life. Andy Warhol and F. Scott Fitzgerald might well have been the patron saints of Manifesto's heady mix of luxury and cold detachment." Paradoxically, Manifesto is notable for its title track, perhaps the closest Ferry has ever come to political commentary—that is, when he wasn't covering Bob Dylan. But wait! "Manifesto" was inspired by a poem by sculptor Claes Oldenburg, "I Am For An Art." Thus Ferry's manifesto is open-ended: "Hold out when you're in doubt/ Question what you see/ And when you find an answer/ Bring it home to me."

The sleeve of 1980's Flesh + Blood sports three "Little Olympiad Nymphs," according to its co-creator Antony Price, as quoted by Buckley. Buckley himself characterized the slick new Roxy as being "packaged for the Saatchi & Saatchi generation," referring to the British ad agency whose "Labour Isn't Working" campaign had aided Margaret Thatcher's ascendancy the year before. Personally, I find the nymphs vaguely Aryan, and am reminded how Ferry, six years prior, showed up on the stage of the West German television program, Musikladen, in what only can be described as Sturmabteilung drag, the uniform of Hitler's paramilitary brownshirts. (In 2007, he would notoriously tell the German weekly Welt Am Sonntag how he admired "the mass marches and the flags," amongst other trappings of 1930s Deutschland dramatics.)

|

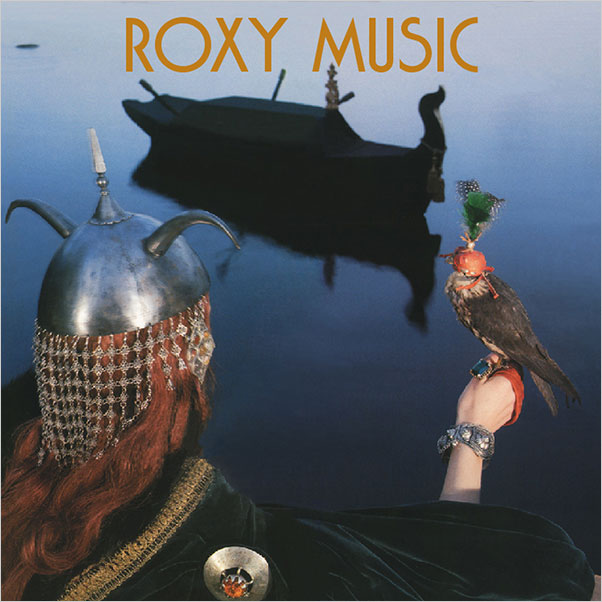

| Mockup of an alternate Avalon cover, revealing the helmet's jeweled temple and a large blue stone on the hand of the "warrior queen." Ferry opted for a dark, near-silhouette image. |

|

| Wearing opulence on its sleeve. The cape pin from the front cover rests on deep green velvet fabric, on the jacket's verso. (Click to enlarge) |

The cover of the last Roxy Music album, 1982's Avalon, at first glance appears to be uncharacteristically masculine. It certainly is the band's least goofy or contrived. But surfaces being surfaces, we now know that the cover "depicts the future Mrs Ferry, Lucy Helmore, dressed as a warrior queen, merlin on arm, looking out over a lake into the distance," as described by Buckley. Just above the album cover's bottom edge is a large jeweled cape pin, reproduced on the cover's verso. In its center is a bright red, yet somewhat included stone, surrounded by a tooled design of crosshatched tree nuts and leaves.

Graphic designer Peter Saville, who had cut his teeth on a series of arresting sleeves for Joy Division and New Order, contributed to Avalon's cover as well as designing the cover of the single of "Take A Chance With Me" backed with the dance mix of "The Main Thing," pictured below, with its parcel of loose stones.

|

| Black and white. A sprinkling of diamonds on a granite backdrop. (Click to enlarge) |

The promo video for Avalon's title song depicts the winding down of a party (per the lyric) in a stately hotel or castle. Roxy Music is on the bandstand as a young woman finishes dining with two bejeweled elders. The young woman is impelled to leave her seat ("When the samba takes you/ Out of nowhere"). She beckons to Ferry and—"dancing, dancing"—the two do so. He touches the shoulder of her tulle gown; she leaves ("When you bossanova/ There's no holding"). She turns to the camera, displaying substantial earrings of wrought gold ribbons and drop pearls. A merlin—the same from the album cover—alights on Ferry's gauntleted hand. The woman spins and spins in an empty dining room as a servant (looking an awful lot like Pet Shop Boys' Neil Tennant) holds a gleaming silver salver.

|

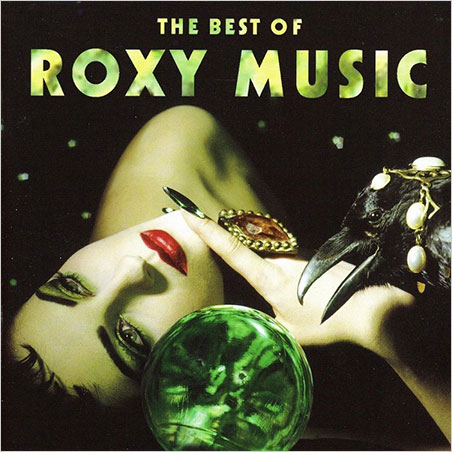

| Still Life with Raven. In 2001's best-of—the tenth of Roxy's twelve compilations (culled from only eight original studio albums)—even the fingernails are jeweled. |

I Love How You Love Me: Bryan Ferry's Solo Career

Two months after the release of Roxy Music's second LP, Bryan Ferry began work on his first solo effort, These Foolish Things, which was made more effortless by virtue of it being a collection of covers of artists as diverse as Erma Franklin ("Piece of My Heart," which had been a hit for Janis Joplin), the Rolling Stones ("Sympathy for the Devil"), and the Paris Sisters ("I Love How You Love Me," their second single with Phil Spector). Another Time, Another Place (1974) was more of the same, with only the title track being composed by Ferry. On Let's Stick Together (1976) Ferry alternated another set of cover songs with—get this—Roxy Music covers, having had second thoughts, according to Buckley, about his original singing ("too strained") and the album's production ("not quite the ticket"). In Your Mind (1977) consisted of all-original material.

|

From these releases, only the promo for "You Go to My Head," from Let's Stick Together, projects the sumptuous style that typifies so much of Roxy/Ferry's other videos. It begins with a woman's hand creepy-crawling towards an ornamental oval doorknob. She wears a ring (above) with a large teardrop stone, possibly an aquamarine—the variety of blue beryl that Ferry would use so stunningly 34 years later. (Later we see that her pink strapless gown is pinned with a large dark stone amid a diamond starburst.) She enters the room, to Ferry in black tie on a nondescript settee, drink in hand. With a flourish—as on a burlesque stage—she doffs her cape, then disappears. "You go to my head," Ferry croons. Get it? We catch a glimpse of her face. Is it cover star Kari-Ann Moller? Regardless, we are meant to remember: as she takes another turn with her cape, the framed Roxy Music cover above the fireplace mantle is revealed, and later, by lighter-light, her eyeshadow is shown to be a less lurid edition of the Roxy Music original. In the final shot this now-we-see-her-now-we-don't chimera strikes a pose on Ferry's couch—as strained as on the Roxy album covers. This together-yet-apart treatment would be repeated in 1993 with the promo for "Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?" (as discussed below).

With 1978's The Bride Stripped Bare, Ferry returned to cover songs sprinkled with his own material. He also introduced a Roxy-esque image on the LP cover, although this is the first such a one that he delegated to longtime collaborator Antony Price and graphic designer Cream, rather than involving himself. In the image, actor and model Barbara Allen, who had appeared the year before in Andy Warhol's Bad, lies on a marble slab, draped in a gold lamé sheath, a live snake slithering off her arm. "Here the biographical merges with the abstraction of Dadaist sloganeering," Buckley writes, referring to the LP's title, which Ferry lifted. To explain…. The Abstraction: as art historian John Walker writes, one of Ferry's teachers at Newcastle, pop artist Richard Hamilton, "was investigating the work of Marcel Duchamp." One of Duchamp's most famous works is The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. The opening track, "Sign of the Times," also employs the title: "Red is the bloody sign of the times/ The bride stripped bare/ Of all despair/ We're cut, but we don't care." The Biographical: The year before, Ferry's lover Jerry Hall notoriously had left Ferry for Mick Jagger. "Publicly humiliated and exposed to the press, Ferry had, indeed, been stripped bare," as Buckley puts it. Appropriately, the video for "Sign of the Times" leads off with newspaper headlines and Ferry's image plastered on the front page. Ferry, on a dais, stands before Fahrenheit 451-style wallscreen transmissions of totalitarian, paramilitary and constabulary images, black flags (and shirts), stills of jeweled women in evening wear engaged in a hand-to-hand brawl. A bald eagle surveys the scene, on-set and on-screen. Rather than a representation of fascism's facility with pomp, which Ferry admired, this is a more intimate warning of what could come.

|

Seven years later, with Boys and Girls (1985), fashion statements are woven through the videos, exclusively. "Slave to Love" begins (and ends) with a languid, earringed woman rotating on a chair as part of what appears to be window dressing, but as a man walks by, it recalls the one-way mirror of a peep show. Next, shots of men waiting, waiting. Slaves to love? No, just paparazzi impatient for Ferry's arrival by private jet. Next, shots of women sumptuously attired, waiting, waiting. Finally, Ferry enters a posh apartment, the photographers in tow. They leave when they catch sight of the figure with Ferry in the bedroom: his daughter. (Madonna would use this same punchline in her 1998 video for "Substitute for Love"). In "Don't Stop the Dance," contemporary go-go models adorned with bling shake a tail feather before green-screen images from early Hollywood dance numbers. In "Windswept," Ferry's muse (didn't we just see her in "Don't Stop the Dance"?) wears ethnic-styled rectangular rings crafted from iridescent stone, and bracelets with leaf-shaped danglers.

Bête Noir (1987), all original songs, featured stunning album art. The front cover is a saturated image of Ferry, his fingers reaching for an obscured cigarette, his left eye enveloped by a silhouette at once reminiscent of the Egyptian Eye of Horus (upended) and a cranial socket. The inner image of Ferry and the track list (he took all titles from films) are both superimposed over what looks to be a golden pharaonic portrait in profile. Two more images of Ferry complete the back cover; the left greenish and just shy of determined, the right distorted like a Japanese anime character. The "Limbo" promo video is a Josephine Baker-Zouzou-esque exercise in Dark Continent exoticism. Finely crafted, but racially repugnant.

|

| Teller or told-on? The introductory sequence of "Kiss and Tell" features two iconic mid-century moderns. They know something, and may not be keeping it under their hats. |

"Kiss and Tell" is a sort of prequel to "Slave to Love." With flashbulbs popping, two monochrome matrons in furs have their backs to the glare, doubly illuminated by scandal sheet projections. Compelled to turn, they do so with a calculated reticence, these women of a certain age, dripping in diamonds, vulnerable perhaps, but with a card up their jeweled sleeve. These are of a different order from the snazzy lasses lip-synching the chorus. Even if I cannot identify with these women, I am truly moved by this style with substance, however fleeting.

"The Right Stuff" lets its hair down a bit, too, with the dancers actually appearing to enjoy themselves. Surely the entire video, shot in glorious 16-mm (or simulant), is a series of outtakes. Few bijoux, but for a killer quadrangle of ice in the (lyricked) middle eight at 2:56—and, of course guitarist Johnny Marr's signature earring.

With Taxi (1993), Ferry returned to cover songs. Like so many British rockers, he'd originally been inspired by African American artists, and so it's not necessarily surprising that he'd lead off with Screamin' Jay Hawkins's "I Put a Spell on You." Fellow Brits Eric Burdon and Arthur Brown, among others, had put their stamp on the song nearly thirty years before, but none could top Hawkins (who I saw before his death in 2000), because none would dare approach his shtick, though artists like the Cramps likely were inspired to do their own. What I'm most intrigued by in Hawkins's lyric, in light of Ferry's own story, is the insistence of placing the spell, not to possess the previously unattainable but rather, "because you're [already] mine." Of course, the possession of a partner is impossible, as Ferry knew too well, having become dispossessed of Jerry Hall (and she of Mick Jagger). Ten years hence he would divorce Lucy, after twenty years of marriage.

|

The promo video of "Spell" features Ferry at the piano of a magical-realist nightclub, accompanied by banjo and bass (Gail Ann Dorsey). Club denizens appear to include musician Boy George and director Pedro Almodóvar muse Rossy de Palma, who swoons when George ignites an incendiary flare, after potions are sprinkled in other barflies' smoldering quaffs. Two pretty spectacular diamond necklaces make appearances in the promo (one shown above) as well as that for "Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow" (shown below), draped around the neck of celebrity Anna Nicole Smith. Another promo from Taxi, "The Girl of My Best Friend," has icky imagery from what might have been a bad Guy Maddin film: retro painted ladies adorned with dangly costume jewels, coyly caressing, suggesting with suckers, plucking berries impaled on lacquered nails (and impaling a heart-shaped balloon), binding each other in red rope; in short, un cliché facile.

|

The promo for "Don't Want To Know" from Mamouna (1994) takes its lead from "The Girl of My Best Friend," a kaleidoscopic nightmare in leopardskin, glitter, chocolate and jewelry boxes, gilt frames and birdcages, artificial flowers, jeweled Super 8 cameras, sliced fruit, and other artifacts from Ru Paul's attic.

|

| Don't want to watch. This still from "Don't Want To Know" has Bryan Ferry trapped in an ornate mirror, further framed by sliced citrus and pomegranates, flanked by bejeweled clones. |

The video for the title song from Mamouna (1994) depicts fantastically veiled creatures as they drag a shackled girl past a tethered monkey into a north African courtyard, dumping her at the edge of a pool attended by a hookah-puffing mermaid in a Helmet Newton orthopedic neck brace. Ferry is a brun Peter O'Toole in Omar Sharif black. Riding crops, high-heeled hooves, a jeweled ram's horn headdress, a knife, a key, more shackles, a pastiche of jewelry. The promo was so transgressive that an alternate was released in the U.S.: all very Anthony Bourdain, as bland as the original was piquant. The promo for "Your Painted Smile" hikes "Mamouna"'s garish tones, with neon-hued models literally holding false-front "smiles" like harlequin masks. Again, a pool is the centerpiece, with the women repeatedly torturing a goldfish. As Ferry sings from behind a Plexiglas scrim, this one's all photo-shoot moves, ill-suited to a moving image. Finally, Ferry pops out a still camera. An errant black chain from "Mamouna" makes an incongruous cameo. The bling: a nose ring.

Coda

—From "Reason or Rhyme"

As I mentioned up top, my video viewing ended with the Mamouna promos, but of course Ferry's career continued, notably with 2010's Olympia. In Olympia's video for "Shameless," Bête Noir's bejeweled dancers make a reprise appearance, shamelessly strutting their stuff as the world burns. "Reason or Rhyme" really is an ad for the album, with its montage of the band in the studio and supermodel Kate Moss (Olympia's cover star) on her bed. Apart from the the other jewels pictured both on and off Moss's nape (about which more below), at about 2:30 the video features a brooch-like object of dark filigree, seemingly set with stones. There are "the making of" shots: browsing through pin-ups (to which Ferry likened Manet's own masterpiece, titled Olympia), discussions with photographer Adam Whitehead, more impossible stiletto heels, sequined and gilded mash-ups from the other Olympia promos, and many cooks evidently not spoiling an optic, audial broth. In the video for "You Can Dance" (and remix) we're taken to a gals-only ballroom, with Ferry and band onstage. Glittering jewels and gyrating hips in sequined shifts, with no one paying attention to anything, except the occasional camera. As golden maxi-sized confetti fall at video's end, we're uncomfortably reminded of Manifesto's lifeless mannequins.

|

| Dancing while the world burns. One can appreciate the irony of YouTube's title, "SHAMELESS PROMO VIDEO [sic]," for this track off Olympia. |

One audio track is worth mentioning, since, in a sense, it brings Ferry full-circle back to his Roxy days: a cover version of Tim Buckley's "Song to the Siren," which had been given a major makeover in 1983 by This Mortal Coil, the faux supergroup cobbled together by Ivo Watts-Russell from the scores of acts on his 4AD record label. A behind-the-scenes promo for Ferry's version credits his own cast of thousands, including Jonny Greenwood (Radiohead), David A. Stewart (Eurythmics), Nile Rodgers (Chic), David Gilmour (Pink Floyd), Oliver Thompson, Phil Manzanera (Roxy/Ferry veteran), and the late David Williams (Michael Jackson, Madonna)—and that's just the guitarists.

|

Kate Moss was the album's cover star, and famously so, because Ferry took his entire oeuvre, including the Olympia photo session shots, on the road to gallery after gallery. He conceived of the cover image as a latter-day Manet, whose original Olympia had its own precedents in Titian (Venus of Urbino), Goya (La maja desnuda) and others. For his Olympia, Ferry swapped the model's black velvet choker—her only attire save earrings, a bangle, a blossom, a single ruffled mule—for a resplendent necklace, selected by Ferry himself according to Nowness, a chronicle of high-life culture. He located the jewel at S. J. Phillips, dealers in antique jewelry and silver in London. The firm's Max Michelson told me the necklace, by an unknown maker from the 1840s, was crafted of approximately 120 carats of aquamarine, mounted in yellow gold, which was rendered white in post-production. (It has been sold.) For the album cover, Ferry abandoned the contortions of Roxy Music and Siren. Those had been accomplished by sculptor Marc Quinn four years before with his portrayal of Moss in Sphinx. It was Moss herself who opted for Roxy-red lips, per Ferry's website. If somewhat crowded, the image is simple, elegant. Leave controversy to artists like Manet who bettered Caravaggio—the latter had used sex workers as his models—by actually portraying one in his Olympia.

Bitters End

—From "Bitters End"

In the end, Ferry's employment of high (and low) fashion and sexually provocative imagery is nothing new, or old, if one wants to point fingers at many other rock and hip-hop artists. What is remarkable is the longevity of Ferry's forty-two-year career and its relative consistency.

As time goes by…

__________

References (Note: Copyright of all images and quotations is held by the original artists and authors)

- Auslander, Philip. 2006. Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Buckley, David. 2004. The Thrill of It All: The Story of Bryan Ferry & Roxy Music. Chicago: Review Press.

- Bufwack, Mary A. and Robert K. Oermann. Undated [1995]. Liner notes for Wild, Wild Young Women. Various artists. Rounder Records 1031.

- Frith, Simon and Howard Horne. 1987. Art Into Pop. New York: Methuen.

- Nicholl, Charles. 1975 (24 Apr). Bryan Ferry: Dandy of the Bizarre. In Rolling Stone.

- Paoletti, Jo B. 2015. Sex and Unisex: Fashion, Feminism, and the Sexual Revolution. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Penman, Ian. 1989. The Shattered Glass: Notes on Bryan Ferry. In Angela McRobbie, ed. Zoot Suits and Second-hand Dresses: An Anthology of Fashion and Music. Boston: Unwin Hyman.

- Rock, Mick. 2006. Glam: An Eyewitness Account. London: Omnibus.

- Walker, John A. 1987. Cross-overs: Art Into Pop/Pop Into Art. New York: Methuen.

This essay was published May 16, 2014, with an added reference (Paoletti) October 27, 2015.