Gods, Graves & Sapphires*

An editorial by William F. Larson, President, Pala International

Fifty years ago I developed what has become a lifelong fascination with mineral specimens. I was enthralled by these small marvels of nature and have collected them ever since, including gemstones – minerals fashioned by man. What first began as physical attraction later developed into a deep sense of appreciation of the natural beauty of these rare, durable objects found in our planet Earth. But recent events in the field of gems have left me with a deep sense of foreboding.

|

| Strange fruit. Beryllium-diffused orange sapphires purchased in Bangkok by the author in Dec., 2001. Photo: Robert Weldon |

Strange fruit

In late 2001, on a buying trip in Bangkok, I purchased a

number of extremely beautiful orange sapphires. The color

of many fell into the padparadscha region, that sunset drenched

lotus land that constitutes the most coveted of all fancy

sapphires.

From the quantity of stones on

offer, only the optically challenged could miss that a new

treatment process had been discovered, but with reassurance

from the sellers that only heat was involved, I happily

bought up a handful of these odd oranges.

Back home, I learned these were

strange fruit indeed. The AGTA

lab’s Ken Scarratt had also obtained samples of

these citrus sapphires and discovered disturbing orange

color rims surrounding pink cores.

Encroaching on

nature

Conversations over the next several weeks culminated in

the revelation by the GIA’s

Shane McClure at the 2002 Tucson show that unnatural

amounts of beryllium had been found in the yellow-orange

layers. In other words, the stones were being artificially

colored by the addition of beryllium (Be).

Doubtless this treatment was discovered

when a piece of chrysoberyl was accidentally heated with

some sapphires. But when masses of these once-rare colors

appeared in the market (one Japanese lab reportedly certified

over 20,000 alone), we should have suspected that this was

not just our parents’ home cooking. Meanwhile, beryllium

treated yellow sapphires appeared, then rubies and still

later, blues.

By mid-2002, thanks to the work

of John Emmett, George Rossman, Ken Scarratt, the GIA and

others, we understood the coloring mechanism. But identification

was altogether another matter. Not all Be-treated stones

showed obvious color rims. In many cases, particularly in

the yellows, the beryllium penetrated completely through

the gem, making it undetectable with ordinary gemological

equipment.

At a certain point, the coin rolled

into the abyss. I realized that, as good a gemologist/ mineralogist

as I am – I could not tell when a stone had been berylliumized.

Indeed, today most stones require sophisticated analysis

at over $400 per sample, and it is unlikely the cost of

testing will fall quickly.

This revelation shakes me to my

core because, as a mineralogist I know that while gem-quality

ruby and sapphire is scarce, ordinary corundum that might

be treated into gem-quality ruby and sapphire is decidedly

less so. Indeed, tons of treatable material are potentially

available from multiple localities.

|

| Orange rim surrounding a pink core in a beryllium-treated orange sapphire from Madagascar. The color rim is visible when the gem is immersed in di-iodomethane and is evidence of a treatment applied after cutting. Note that recutting such stones will produce a loss of the orange color. Photo: R.W. Hughes |

Unnatural acts

Discussions with my friends John Emmett and George Rossman

have crystallized this for me. According to these experts,

there is probably no sapphire that is naturally heated in

the ground over approximately 1400° Celsius. Fine natural

sapphires and rubies are subjected to far lower temperatures

in the ground than that produced via modern heat treatment.

Simply, when world authorities

tell me that unnatural acts happen to corundum at temperatures

beyond 1600° Celsius, I can clearly read the writing

on the furnace wall.

On the edge

In the past three decades, heat treatment has increased

the availability of gem-quality corundum perhaps a hundred

fold. But with today’s beryllium treatments and those

face-lifts not yet discovered we teeter on the precipice

of what might be a 100,000-fold amplification of supply.

Can our industry withstand this?

There will be those who argue

that the increase in supply only serves to sate ever-increasing

demand. But such notions cannot withstand even cursory scrutiny.

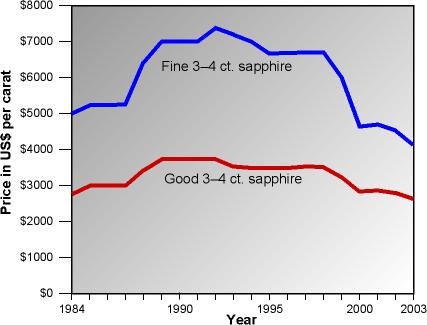

The

chart below was compiled from The Guide’s price

sheets. It tracks sapphire prices for 3–4 ct. stones

for the years 1984–2003. Note that sapphire prices

are actually lower today than they were some 20 years

ago, even though the demand for sapphires has increased

along with the world’s population.

|

| Graph tracking the price of 3–4 ct. sapphires over the past 20 years. The Good category corresponds to levels 5 and 6 in The Guide, while Fine represents levels 7 and 8. Price data courtesy of Stuart Robertson of The Guide. |

What could

account for such flat prices? It’s certainly not increased

production. The only answer that makes any sense is treatments.

Treatments make it possible to use more and more of existing

production, thus keeping sapphire prices artificially low.

It is not low prices that bother

me, but the fact that treated stones raise expectations

to unreasonable levels. The sublime beauty of nature is

lost.

We already see this today in the

ruby market – to the degree that treated stones often

make it difficult to sell the natural product. Treated rubies

from Möng Hsu in Burma have so snookered the senses

of the buying public that many no longer recognize the true

face of nature. A gorgeous natural creation like the Matterhorn

is now reduced to the equivalent of a ride at Disneyland.

The blue topazization

of sapphire

We have now come to this point: my company will not buy

gemstones that are potentially beryllium treated. From now

on, we will only purchase stones we can be sure have not

been treated in a radical way. If testing is too expensive,

we will be forced to carry only natural stones, or those

heated at low temperatures.

Why? Because corundum is not a

rare mineral. It is only rare in gem quality. If treatments

can take quantities of non-gem material and turn it into

gems, then there will be no more value.

I remember when blue topaz cost

$50/ct., then $40/ct., going down to $10/ct., and now what

is it… $2/ct.? Like corundum, ordinary topaz was never

rare. But naturally occurring blue topaz was quite scarce.

The moment man figured out how to turn the ordinary into

the extraordinary – with no easy way to separate the

two – the price plummeted.

|

|

| Top: Rough industrial

grade sapphire from Africa prior to beryllium

diffusion. Bottom: The same sapphire after beryllium diffusion and then preforming. Tons of such material exists. (Images courtesy of John Emmett) |

Beryllium poisoning

Now that we have the extraordinary ability to color corundum

(a treatment that involves far less sophistication than

production of blue topaz), what should be the price for

corundum artificially colored by man? What is the difference

between artificially colored corundum and a synthetic ruby

or sapphire made out of re-crystallizing naturally occurring

grains of corundum? These are important questions. Some

might dismiss them as philosophical minutiae unworthy of

attention. I would say they are fundamental to the existence

of our trade, which stretches across millennia of human

history. Our trade is a link with the past, both human and

geologic, and in that sense, it transcends eras, transcends

fads, goes to the root of who we are and where we have come

from.

Gems whose supply is subject to

human ingenuity rather than Mother Nature are common. Therefore,

such stones have only the value humans are willing to put

on them. Yes, all gems are fashioned by man, but what happens

when man’s handiwork extends not just to smoothing

out surface imperfections with grit and grinding wheel,

but also literally to redecorating the atomic grid? This

is where man tries to become god. And where nature –

poisoned – falls into the grave.

As I said before, not only do I

buy and sell gems, but I also collect. These rare natural

creations are my passion, among the greatest loves of my

life. With the gems I buy, sell and collect, I want those

formed by nature. I want no part of playing god or executioner.

I’ll leave that to the creator.

Footnote

* With apologies to C.W. Ceram, author of Gods,

Graves & Scholars

Further reading

- Orange-pink sapphire alert by the AGTA GTC, posted 8 Jan., 2002

- The Skin Game – by Richard Hughes, covers the earliest developments on beryllium treated orange sapphires in a comprehensive article. Fully illustrated. Posted Feb. 2002.

- From Gems & Gemology: GIA researchers uncover important data on new treated corundum by the GIA, posted 15 Feb., 2002

- Understanding the new treated pink-orange sapphires by John Emmett and Troy Douthit, posted 13 May, 2002

- Beryllium diffusion of ruby and sapphire by John L. Emmett, Kenneth Scarratt, Shane F. McClure, Thomas Moses, Troy R. Douthit, Richard Hughes, Steven Novak, James E. Shigley, Wuyi Wang, Owen Bordelon and Robert E. Kane, Gems & Gemology, Summer 2003, pp. 84–135.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Stuart Robertson of The

Guide for supplying the price data on sapphire and John

Emmett for the photos of beryllium-treated blue sapphires.

Thanks also to John Emmett, George Rossman, Ken Scarratt,

Shane McClure and James Shigley for enriching conversations

on corundum. Title photo © R.W. Hughes.