Paraiba at Pala

Note: This article was published in conjunction with our August 2006 Gem News featured stone. It includes these subsequent updates:

- Skip to Paraiba Follow-up (November 19, 2008)

- Skip to Paraiba Follow-up (May 15, 2007)

- Skip to Paraiba Follow-up (February 20, 2007)

- Skip to Paraiba Follow-up (September 14, 2006)

August 16, 2006. Much has been written about the discovery of facetable copper-bearing (or cuprian) tourmaline, often known by the name of “paraiba,” from Paraíba, the tiny, easternmost state in Brazil where the stones were first mined. The saga of the stone and its early champion, Heitor Dimas Barbosa, is recounted in articles such as the ICA’s “Paraiba Tourmaline” and Laurie Kahle’s “Big Blue,” published in Robb Report Magazine, September 2004.

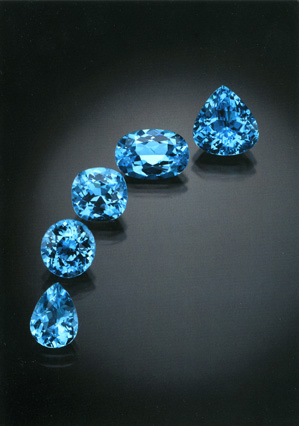

|

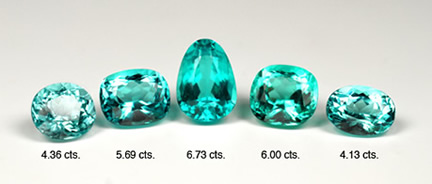

| A suite of paraiba tourmalines, demonstrating the variety of hues. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

For a period of five years beginning in 1989 the stones were produced from a small mountainous area near São José da Batalha. While the crystals were never very large, mining today yields little above one carat in size—as if prophesied by the motto inscribed on the Paraíba state flag: NÉGO (Portuguese for “I deny”). Nevertheless, the mining continues in Paraíba and other nearby localities, as this December 2005 Gemmological Association of All Japan report indicates. But our featured stone (August 2006) comes not from South America, but from Africa.

|

| Highly fractured, Brazilian paraiba tourmaline crystals are almost always under a carat, as can be seen in this photo of panning at the Mulung mine, which produces about 300 cts. per month. (Photo: Gemmological Association of All Japan) |

“Is Mozambique the New Paraiba?” is a question asked by Richard Wise, jeweler-gemologist and author, on his blog GemWise. This east African country is the latest to mine copper-bearing tourmaline, following a 2001 discovery on the west coast, in Oyo, Nigeria, near Lagos. An ICA article on paraiba claims that the bi-locality of the gemstone between continents “clearly illustrates the phenomenon of the continental drift,” since the coastlines of South America and western Africa “fit like a jigsaw puzzle.” (Whether this claim is muddied by the discovery in Mozambique—2500 miles across the continent—isn't addressed.)

|

| An exquisite copper-bearing tourmaline from Mozambique, 14.2 cts. Available from Pala. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

For fans of the rare Brazilian paraiba, new discoveries were welcomed—but with a healthy dose of skepticism, as demonstrated by a GemOnline.com exchange between Wise and others, last March. Purists want to distinguish between Brazilian paraiba and African copper-bearing tourmaline. Wise himself has written in his weblog that Mozambican material “is said to be a more uniformly ‘aquamarine blue’ than gems from the Brazilian find,” but because the African mines routinely produce sizes larger than five carats, the bigger stones “seem to hold the color better and appear to have saturation closer to their Brazilian counterparts.”

|

| Above: Like their Brazilian cousins, these untreated cuprian tourmalines from Mozambique show a fantastic range of hues. Below: Variety abounds in saturation as well. This suite of heated stones runs the gamut from a limpid aquamarine to an electric blue-green. Available from Pala. (Photos: Wimon Manorotkul) |

|

Subjective as this might be, GIA’s Gems & Gemology (Spring 2006) stated that, when mixed in with Brazilian stones, saturated blue-to-green material from the two new localities “cannot be distinguished from the Brazilian material by standard gemological testing or on the basis of semi-quantitative chemical data (obtained by EDXRF analysis).” Spectrometry conducted via LA-ICP-MS, however, successfully revealed chemical fingerprints for material from each of the three countries.

|

| At 57.19 cts., this stone from Mozambique makes plain the larger sizes of African cuprian tourmaline currently obtainable. Available from Pala. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

Such fingerprinting was acknowledged by the Gübelin Gemmological Laboratories (GGL) in its announcement, last month, regarding wording on its reports. (Note: See also this February 2007 clarification of GGL’s analytical and reporting policies.)

The blue, bluish-green to greenish-blue or green elbaite tourmalines containing copper- and manganese are now uniformly called “Paraiba”, regardless of their country of origin. However, in order to distinguish between the original Brazilian sources and more recent discoveries (currently Mozambique or Nigeria) the origin of these stones is also disclosed on the report.

In fact, a July 31, 2006 GGL report reads as follows, with a note attached explaining the various localities of cuprian tourmaline.

Species: Natural Elbaite Tourmaline

Variety: Paraiba

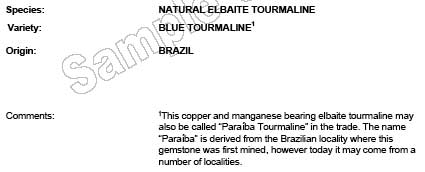

The American Gem Trade Association lab received feedback at its June membership meeting that such nomenclature was unhelpful at best and deceptive at worst. A sample report received by Pala just last week reads:

Group: Natural Tourmaline

Species: Natural Elbaite

Variety: Cuprian Blue Tourmaline (This copper bearing variety of elbaite is sometimes called paraiba tourmaline in the trade.)

Origin: Nigeria (The data obtained during the examination of this stone indicates that the probable geographic origin is as stated...)

Finally, a June 15 “results of advanced testing” letter from the GIA Laboratory, after stating its chemical analysis, concluded:

In our opinion, the chemistry of this tourmaline is consistent with data we have recorded on other copper-bearing elbaite tourmalines.

Clearly the name game is still being played. Umbrella terms such as Pangaea tourmaline have even been suggested, with a nod to the pre-continental-drift connection. Given the unabated excitement generated by these beautiful stones, we can expect the debate to continue. [back to top]

Paraiba Follow-up (September 14, 2006)

Lab Trade Groups Take On Paraiba

|

Following up on last month’s overview of paraiba-type tourmaline, we’re providing examples of wording and nomenclature used by several high-profile labs in their reports. At issue is whether copper-bearing (or cuprian) tourmaline, regardless of its provenance, should be labeled “paraiba” (the locality of its first discovery). Laboratory trade groups around the world have addressed the subject, so we begin with them.

LMHC Approach

This issue has been addressed by the Laboratory Manual Harmonisation Committee (LMHC), formed in 2002 by seven major labs to create standardized report language. According to one member lab, AGTA’s Gemological Testing Center (GTC),

consensus was finally reached in April. New gemstone identification reports will call all copper containing elbaite “paraíba tourmaline,” regardless of their origin. This is consistent with current trade practice. To highlight the fact that these gemstones may come from different origins, however, there will be a comment stating that the description is a variety name only derived from the locality in Brazil where it was first mined.

A LMHC “Information Sheet: Standardised Gemmological Report Wording” was due to be released in June. These documents can be found on the websites of several of the member labs, such as GGL, GIT, and AGTA-GTC.

GILC Approach

Earlier, in January 2006, members of a similar group, the Gem Industry and Laboratory Conference (GILC), agreed that “copper manganese elbaite tourmaline in the typical neon or electric blue-green shades could be described as paraiba tourmaline, irrespective of its source,” as reported in the September 2006 issue of Jewellery News Asia. The article goes on:

The consensus on applying Paraiba tourmaline as a variety name instead of an origin name removed the heat from a nomenclature debate that had been building up in the trade as laboratories found they were unable to distinguish between material from Mozambique and that from Brazil.

Japanese Approach

The Jewellery News Asia article states that prior to May 2006, Japan’s lab rules allowed only Brazilian material to be labeled “paraiba tourmaline.” On May 1, the Association of Gemmological Laboratories in Japan allowed cuprian tourmaline to be described as paraiba tourmaline, regardless of country of origin. The decision is comparable with those of the GILC and LMHC.

In the article, Nilam Alawdeen, chair of the International Affairs Committee of the Japan Jewellery Association, elaborated:

In the standard report, the stones will be described as tourmaline with a colour prefix, for example, blue tourmaline or blue-green tourmaline. The change is in the analysis report which laboratories usually attach to a standard report. Prior to May 1, 2006, analysis reports were issued only for this type of tourmaline from Brazil. ... Following the amendment in May... laboratories are now allowed to apply the trade name Paraiba tourmaline to blue to green elbaite tourmaline from other sources...

The reason given for the change is the difficulty labs had in positively distinguishing locality of origin. As we reported above last month, however, the material is indeed distinguishable via LA-ICP-MS spectrometry, but we didn’t mention that because this is a laser procedure in which a small sample is vaporized, such as occurs in LIBS testing (see our LIBS follow-up).

Preliminary Conclusion

Based on the evidence assembled, it appears that it’s now possible for reports to identify

- the variety name paraiba tourmaline (as an indicator for copper-bearing elbaite), as well as

- the locality, assuming that a chemical fingerprint by LA-ICP-MS or other method is requested and performed.

Sample Paraiba Reports

We turn now to a sampling of high-profile labs and how they’re putting the new rules into practice.

GAAJ Reports

We were unable to obtain a sample from the Gemmological Association of All Japan (GAAJ), but its English-language home page lists prominently the Gems & Gemology LA-ICP-MS article we referenced last month, so the lab obviously is aware that locality determination of cuprian tourmaline is feasible. According to the Jewellery News Asia article, however, GAAJ “is not issuing country-of-origin reports for this type of blue tourmaline.”

The article quotes Satomi Yanagihara, a GAAJ gemologist:

The chemical composition of the stone is not detailed in the report. However, if a client requests an analysis report we do a special test to confirm the presence of copper and manganese.

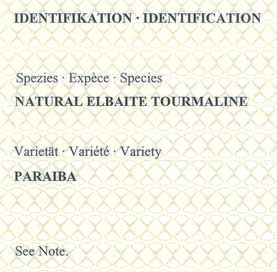

GGL Reports – Revised 2/20/07

The LMHC approach is compatible with a July announcement, reported above last month, by Gübelin Gemmological Laboratories (GGL), a LMHC member:

The blue, bluish-green to greenish-blue or green elbaite tourmalines containing copper- and manganese are now uniformly called “Paraiba”, regardless of their country of origin. However, in order to distinguish between the original Brazilian sources and more recent discoveries (currently Mozambique or Nigeria) the origin of these stones is also disclosed on the report.

An actual GGL report, dated July 31, 2006, includes a second page explaining the characteristics and various localities of copper-bearing tourmaline, but the report itself reads as extracted below, with no mention of locality. Based on the LMHC agreement, however, in cannot be assumed that the locality, if known or requested, would routinely be omitted from such a GGL report. In fact, GGL has addressed the circumstances under which locality may be omitted in a January 2007 response to Pala International, below.

|

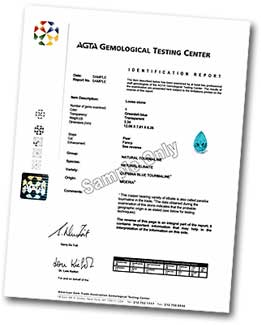

| Extract of actual 7/31/06 Gübelin lab report. |

AGTA-GTC Reports – Revised 2/20/07

The AGTA-GTC reports for cuprian tourmaline also conform to the LMHC agreement, and come in two variations, based on sample reports we received on 2/16/07—one with origin specified and the other with origin not specified. Variety no longer employs the terms paraiba nor cuprian. See the accompanying AGTA-GTC response to Pala International, below.

|

| Extracts of sample AGTA-GTC lab reports, received 2/16/07. Above, with origin specified; below with origin not requested. |

|

GIA Reports

The Gemological Institute of America (GIA) Laboratory is another LMHC member. An extract of an actual letter “providing information on the results of advanced testing” that was requested for a 6/15/06 report is reproduced below.

|

| Extract of 6/15/06 GIA letter “providing information on the results of advanced testing” of a copper-bearing tourmaline. |

While the letter speaks for itself, the Jewellery News Asia article explains that the GIA

is not yet describing Mozambique material as Paraiba tourmaline on its certificates as it is awaiting the final Information Sheet on the subject from the [LMHC]. Gemmologist Ken Scarratt, who represents GIA on LMHC, said GIA’s position is that once the LMHC Information Sheet is completed and ratified by all members, it will implement its content.

At present, GIA issues a standard identification report stating that a copper-bearing stone is a tourmaline, together with an accompanying letter that describes the chemical composition of the specific stone, relates its chemical composition to that of the original [paraiba deposit] and also mentions other sources in Brazil, Nigeria and Mozambique where tourmaline may presently be found. GiA does not issue geographic origin reports.

SSEF Reports – Added 5/15/07

The SSEF Swiss Gemological Institute is also an LMHC member. The language used in SSEF gemstone reports for paraiba-type tourmaline consists of the following.

Identification: Elbaite Tourmaline

Comment: This copper bearing elbaite tourmaline may also be called paraiba tourmaline in the trade.

Origin: Mozambique

Images of Complete Sample Reports

Below are links to images of sample reports. Please note that these reports are for illustrative purposes only and may not accurately reflect current practice by the labs. We welcome any updates; contact Palagems.com.

- Gübelin Gemmological Laboratories (GGL)

- Actual report dated 7/31/06; see also this GGL clarification regarding its reports, below

- American Gem Trade Association Gemological Testing Center (AGTA-GTC)

- Sample report with origin (received 2/16/07)

- Sample report without origin (received 2/16/07)

- Gemological Institute of America (GIA)

- Advanced testing results letter dated 6/15/06 (does not include standard ID report)

- SSEF Swiss Gemological Institute

- No sample available; see wording above

As always, we welcome new information and critiques of our articles. Contact Palagems.com. [back to top]

Paraiba Follow-up (February 20, 2007)

|

Gübelin Lab Provides Clarification of Policies

In response to the discussion above, we received a clarification from Gübelin Gemmological Laboratories (GGL) in January concerning its “analytical processes and reporting policies” regarding copper-bearing tourmaline.

Dr. Daniel Nyfeler, Managing Director of GGL, made the following points regarding the lab’s practices.

- All tourmalines with “paraiba-like” colours are tested for their required chemical composition to qualify [as] cuprian elbaite.

- For each elbaite tourmaline which shows a “paraiba” colour, the origin is determined, [mainly] by means of chemical analysis. [For approximately one year we have been able to] positively distinguish all known sources of “paraiba” tourmalines, i.e., Brazil, Mozambique, and Nigeria... We... communicated this to the trade in our Newsletter #10 (February 2006).

- Please note that we are determining the origin of EVERY paraiba tourmaline, regardless if the client wishes to have the origin mentioned on the report or not. So far, we [have done] this by means of EDS-XRF. The distinction of the three sources [has] so far been very clear and unambiguous. In the future, we might also include results from the LA-ICP-MS machine which we purchased recently.

- Some clients wish to have no origin mentioned on the report. Thus, we have introduced to issue a Note with each Paraiba report, which explains the [original source] (Brazil) and the newer sources (Nigeria, Mozambique). This should provide the client with sufficient information, i.e., alerting them that, although the report says “Paraiba,” the stone might come from a country other than Brazil.

We would also like to highlight that our policy is in perfect compliance with the [Laboratory Manual Harmonisation Committee] policy.

It appears that the sample report we discussed above in August 2006 (and posted fully in September 2006) is a report that was issued, as clarified in point #4 above, for a client who wished to have no origin mentioned.

LMHC Implements Paraiba Standardization

The Laboratory Manual Harmonisation Committee (LMHC), consisting of reps from seven major gemstone laboratories, has implemented its reporting guidelines regarding “paraíba tourmaline” as of January 15, 2007, in Information Sheet #6.

The LMHC provides the following definition:

A paraíba tourmaline is a blue (electric blue, neon blue, violet blue), bluish green to greenish blue or green elbaite tourmaline, of medium to high saturation and tone, mainly due to the presence of copper (Cu) and manganese (Mn) of whatever geographical origin. The name of the tourmaline variety "paraíba" is derived from the Brazilian locality where this gemstone was first mined.

The guidelines require the following.

- “The name ‘tourmaline’ shall be used in either the species or variety section (or both) of the report if the group [which is optional] is not mentioned”

- Origin also is optional, but “[i]f an origin determination is not included on a report the following wording shall be added in the comments section: ‘Geographic origin has not been determined’”

- The variety “Tourmaline” is to be specified if “paraíba” isn’t used

Two variations of comments, explaining the use of the term “paraíba” also are provided. A copy of the LMHC information sheet is available here.

AGTA-GTC Makes New Sample Reports Available

In response to our ongoing reporting of paraiba tourmaline, on February 16, 2007, we received revised lab reports from Dr. Lore Kiefert, Laboratory Director of the AGTA Gemological Testing Center. Dr. Kiefert explained:

We have created new [reports] in order to meet the American demand, where we eliminated the word paraiba from the Variety. We also eliminated the word cuprian since in the Comments section the copper content necessary for a paraiba call is explained... Please note that when an origin is not requested, this will be noted on the report.

The new reports are posted above.

We asked Richard Hughes whether origin is routinely determined by the lab, even if not specifically requested by the client for inclusion in the report. (GGL stated such a practice, as we reported above.) Hughes responded that such origin can be easily established by analysis of the same chemical data used to determine the variety.

As always, we welcome new information and critiques of our articles. Contact Palagems.com. [back to top]

Paraiba Follow-up (May 15, 2007)

SSEF Testing and Reporting of Paraiba Tourmaline

Following our February 2007 update (above) on gemological lab policies regarding paraiba-type tourmaline, we received a note from another laboratory—SSEF Swiss Gemological Institute.

|

| Diagram of LA-ICPMS data (Pb versus log Zn, ppm). Red: Nigeria, blue: Brazil, green: Mozambique. (Diagram © M.S. Krzemnicki, SSEF 2006; used by permission) |

Dr. Michael S. Krzemnicki, Deputy Director SSEF and Director of Education for the institute, forwarded information describing how the SSEF lab is able to determine origin of copper-bearing tourmaline. Using ED-XRF, LIBS, and LA-ICPMS analysis, “careful data plotting reveals distinct differences which allow us to separate the origin of these tourmalines in most cases.”

Dr. Krzemnicki also sent us the language used in SSEF gemstone reports for paraiba-type tourmaline:

Identification: Elbaite Tourmaline

Comment: This copper bearing elbaite tourmaline may also be called paraiba tourmaline in the trade.

Origin: Mozambique

See the full annual report here (1.1 MB; requires free Adobe Reader). [back to top]

Paraiba Follow-up (November 19, 2008)

|

| Paraiba tourmaline from Mozambique. This stone has been sold. |

Name Game: Paraiba Tourmaline

Lawsuit dismissed, but it ain’t over…

If you choose to, you may legally call copper-bearing tourmaline “paraiba tourmaline” due to the recent dismissal of the lawsuit over the rights to the name.* Although there are still many who disagree on the use of the term paraiba for copper-bearing tourmaline found outside the state of Paraíba in Brazil, the term may be used in the trade to describe the neon greenish-blue variety of tourmaline.

Complete disclosure of the origin of the material is still a fully descriptive and ethical way to further denote paraiba. For example, if we use the phrase “paraiba tourmaline from Mozambique,” we should now be politically correct and continue our enjoyment of one of nature’s rare jewels.

______________

*The lawsuit was dismissed by U.S. District Court Judge Ronald M. Whyte on October 27 “with prejudice for [plaintiff’s] failure to respond to the court’s order to show cause and for failure to diligently prosecute,” as reported by National Jeweler. Such a dismissal, “with prejudice,” means that the case cannot be refiled. The decision, however, did not keep the plaintiff, David Sherman, from making a “Rule 60” motion two days later, according to a JCKonline story. The story’s author, Gary Roskin, explained that “[a] Rule 60 motion is one where the plaintiffs are asking for a relief from judgment or order, with reasons that could include mistakes, oversights, inadvertence, surprise, excusable neglect, or any other reason that justifies relief.” Nevertheless, the American Gem Trade Association, a defendant in the case, issued a statement October 31 that praised the judge’s decision. [back to top]