The Ruby Mines of Mogok – Chapter Two

This is Burma, and it will be quite

unlike any land you know about…

— Rudyard Kipling, Letters from the East

See also Chapter One, Chapter Three, Chapter Four, Chapter Five Part One, Chapter Five Part Two, and Chapter Six.

Chapter Three: Important Star and Faceted Rubies

|

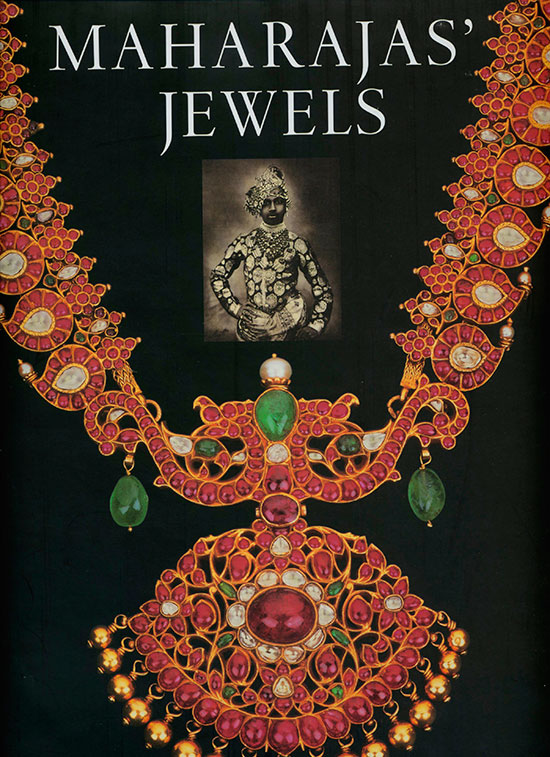

| Martin Ehrmann, in a portrait by Harold and Erica Van Pelt. |

When I returned to Burma six months later I was met by my agent at the airport. He was in a great state of excitement. “While you were gone I discovered some very fine gems you are looking for. They are being reserved for you but we must get to Mogok at once as there are others after them.”

It was Thursday. He had reserved a room at the Strand for one night.

The following morning we were on our way to the airport.

We entered the domestic departure and arrival part of the airport which is never seen by international travelers and tourists. There was a good sized crowd, mostly Burmese, Chinese and a few Hindus. Because of the crowd, there was no place to sit down. Most of the people sat on their luggage or squatted on their heels.

Some slates were hanging on the walls announcing the arrivals and departures of the various planes. Ours was due to depart in 30 minutes.

Because of the slow, dangerous and difficult land communications, air transportation was preferred by all who could afford it which accounted for the size of the crowd. Finally, our departure was called. The passengers began to board, taking all their baggage along with them.

U Khin Maung and I had reserved seats in the rear of the plane and were the last to go aboard. When we were seated and had fastened our seat belts, the motors of the Dakota started up one after the other and we were airborne a few minutes later.

Relaxing on the plane, U Khin Maung finally started to tell me what had happened in Mogok in the past six months. He asked me if I remembered the young gem dealer and mine owner and his mother I had met before leaving Mogok the last time. I asked him if he meant Maung Myint and his mother Daw Phon. “Exactly,” was his elated reply.

“My mother regards Daw Phon as the most reputable dealer in Mogok,” he began and then this strange story was unraveled slowly but surely by U Khin Maung.

A month or so ago Daw Phon had consulted U Khin Maung’s mother about building a pagoda. It was to be the finest in all of Mogok. Daw Phon then confided in her that, some time before, they had struck it rich in their mine in Kyatpyin six miles from Mogok. They had found the finest collection of rubies ever mined in Mogok and considered this find to be worth over two million dollars.

U Khin Maung was breathing heavily with excitement but never stopped talking. He was incoherent at times but I was able to gather that when Daw Phon first met me, she was deeply touched by something I said to her and therefore chose to show her fabulous collection of gems to me first. Her gems were already cut and polished.

It was difficult for me to believe that I was chosen to have first refusal on such a fabulous collection. Like everything else in Mogok, the importance of a gem buyer had to be established beyond a doubt before important gems were shown to him. The leading buyers of gems were mainly Indians and either lived in Mogok permanently or at least spent most of their time there. I couldn’t help wondering why I was chosen to be the first.

In spite of U Khin Maung’s story that it was due to his mother’s influence, I couldn’t quite believe that. It just didn’t make sense.

We were approaching Momeik and landed. When the Dakota rolled to a stop at the airport shack and the door was opened, we were practically the last to deplane as the exit door was in the front and we had the seats in the rear. As we left the plane, we saw a rather large contingent of soldiers around the plane. Usually there are a few but this time there was almost a battalion. We learned they were there in such large numbers because only the day before the warehouse of the airport had been broken into by insurgents or dacoits [armed robbers], and several of the guards were shot and killed. We were also told that the activities of the insurgents had increased during the past few weeks tenfold.

U Khin Maung’s jeep was at the airport ready to take us to Mogok. This time we were supposed to have a contingent of soldiers guarding us all the way, but I was advised by U Khin Maung and some of the others who were aware of the situation not to accept such a guard as soldiers would only invite a confrontation with the insurgents. Although our luggage was loaded into the jeep and we were ready for our trip to Mogok, we decided to wait an hour or so so that the caravan escorted by the military went without us.

|

| Gray market. A fedora mingles with traditional guang-baungs (turbans) and conical paneled hats in an outdoor market on an overcast day. (Photo: Martin Ehrmann) |

As I waited, a young man whom I vaguely remembered left an expensive, nearly new American car and approached me. “Hello. Mr. Ehrmann. Do you remember me? I am Maung Myint, the son of Daw Phon. She asked me to meet you and drive you to Mogok in our car as this would be much safer than going in a jeep,” he announced.

The chauffeur of this car was a very young Burmese with a pleasant face. He was a first cousin of one of the insurgents in the area and Maung Myint was sure that he would, thus, not be molested.

The baggage went with the jeep but Maung Myint, U Khin Maung and I rode in the American car and as we drove, the mystery of why I was to have the first look at these gems was solved.

Daw Phon had received a cable from Mr. Bernard, a good friend of mine in the states. He was a long-time customer of Daw Phon and had bought practically all the star rubies that were found in her mine or that she could buy elsewhere. However, he was now over 80 years old and no longer did much traveling. His cable proposed that I be shown the star rubies first if I, in turn, would give him first choice of them when I returned to the States. This, of course, was a wonderful break for me. With so many buyers in Mogok, such stones are sold very quickly.

Daw Phon knew that I was staying with U Khin Maung’s mother and so, when she received the cable she “confided in her so that she could be certain of my arrival time and so that she would be able to have her car meet me at the airport.”

Daw Phon was 70 years old. She was born in Mogok. Her husband died just about five years before. She had three children: two girls and a son. The eldest daughter was married to U Aung Gyaw, a very important mine owner and dealer. Maung Myint, who was married about a year, and the young daughter, still single, lived with their mother. Maung Myint invited us to visit them the following morning.

When we arrived, we shed our shoes, sat down in a squatting position and were served cups of coffee. This coffee was unlike any I had ever tasted. Apparently coffee, milk, water and lots of sugar are cooked together. It had a sickening sweet taste. English biscuits and English cigarettes were also on the mats in front of us. Immediately after the coffee we were offered cups of tea which tasted very good to me after the first unfamiliar concoction.

Daw Phon entered fairly soon and sat down close to us, graciously offering us cigarettes and some of the English biscuits to go with our tea. She discussed the cable she had received from New York and told me how sorry she was that she didn’t know about my friendship with Mr. Bernard when I was last in Mogok.

Time was of no importance. Conversation first was of great importance to the transaction of business in Burma. Daw Phon told me that her husband had been a miner for the Syndicate. Later he had become a mine owner and because he knew the area so well from the old days, he was able to claim the mines producing the very finest rubies and sapphires at that time.

Finally the time had arrived to view the gemstones. The old lady showed me many very beautiful star rubies, the likes of which I had never before seen. They were large, of beautiful quality and the stars were sharp and well defined. These gems were shown me singly and after looking at each stone I voiced my enthusiastic approval. I asked her how many of these she had and she answered, “Many. We can make a deal for the whole lot or for whatever you choose when you’re finished looking.”

|

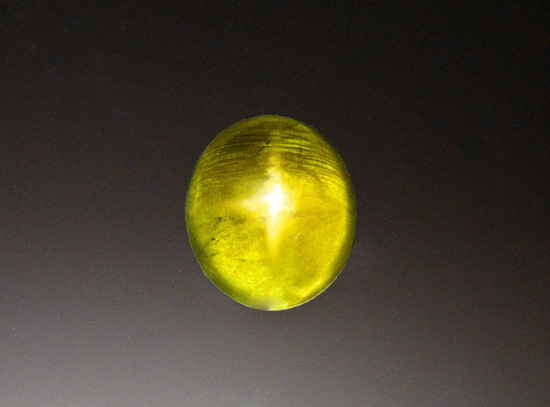

| Martin Ehrmann viewed (and bought) rubies with well defined asterism, such as is displayed in this 5.18-carat cabochon from Burma, measuring 9.82 x 7.92 x 5.87 mm. Inventory #16647. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

After seeing what I thought was all she had, I chose ten star rubies which varied from the largest weighing 22 carats, down to the smallest of about 8 carats and I asked her the price. But she said she had something else she was going to show me before beginning to bargain for these stones.

She then produced a gem that was a bigger surprise than the fine star rubies I had just seen. It was a ruby, oval in shape, beautifully cut and, as the paper indicated, it weighed 20 carats and 22 points. The examination of this ruby took me a long time. I looked at it in the room, then I took it outside into daylight and then I louped it with my 10-power loupe. In spite of a cloud and blemish on some of the back facets, it was surely the finest pigeon’s blood ruby I had ever seen. She followed every move I made. She seemed to have become a different parson. She was very suspicious and her looks were fierce. She appeared to have lost all control of her emotions. But when I finished my examination of the stone, which must have taken me at least an hour, and nodded my approval, I noticed that she breathed easily again and had regained her composure.

The time had come to begin bargaining. This time I was determined to be patient and cool in spite of my excitement. I knew I would buy all the star rubies and the marvelous, gem faceted ruby.

It took me more than a week to make the deal for these rubies. I had to include in the purchase some other small cut rubies weighing from 1 to 3 carats which weren’t so fine but nevertheless of good commercial quality and the price gave Daw Phon enough money to realize her dream to build a marvelous pagoda.

But I had bought a lot of gems more beautiful than any other dealer had ever brought back at one time from Burma!

My next visit was reserved for Mr. A. C. Pain. He had lived in Mogok many years and, in partnership with U Ba Mhi, owned many of the best mines in Mogok. He was a competent geologist and, but for his interest, various rarer gems found in the area would have been ignored as worthless. Most miners were only interested in the more valuable rubies, sapphires and spinels because of their ready market. Luckily these rare gems of not too great value were not neglected by Mr. Pain.

|

| British gem dealer and mineralogist A. C. D. Pain, with whom Martin Ehrmann visited in Mogok. |

The rarer gemstones found in the Mogok area are peridots; danburites of bright yellow weighing up to 40 carats; scapolite and scapolite cat’s eyes of white, pink and blue, and of various sizes up to 50 carats; apatites in blue and green as well as the chatoyant variety which is rather common in Burma; albite cat’s eyes up to 50 carats in abundance. Orthoclase and other varieties of feldspar were found in another area of Mogok about 12 miles northwest of the center of the city. Though less abundant, the following stones are also found in the same area: kornerupine, diopside, iolites, chrysoberyl and zircon. And, occasionally, a new gem mineral is found. Mr. Pain recently found a new species which has been described by the British Museum of Natural History in London as painite. Sphene is another rare gem occasionally found in Mogok. This gem was first discovered when the St. Gothard tunnel in Switzerland was built.

|

| This 20.58-carat danburite from Burma measures 17.42 x 15.57 x 13.73 mm. Inventory #16134. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

Mr. Pain owns a magnificent collection of representative Burmese gems which he is continually improving in quality. When I saw it last, it contained some 250 gems varying in sizes from 2 to 150 carats. The outstanding stones are a blue kornerupine weighing over 20 carats, a sphene of similar size, a pink scapolite cat’s eye of over 20 carats and a fibrolite of the most unusual size. This fabulous gem is now in the Geological Museum in Kensington, London.

Though Mr. Pain was friendly, hospitable and always very nice to me when I visited Mogok, my many efforts to purchase his collection were to no avail. He was actually very resentful of any foreign buyer coming to Mogok. Whenever I expressed a desire to buy anything from him, he always said he had nothing for me.

I spent most of that day with Mr. Pain and was, to my surprise, able to purchase some very wonderful rough crystals of rubies, sapphires and even spinels. He even sold me some duplicates from his collection, a very beautiful blue scapolite cat’s eye and a pink one, the first of this material I had ever had. Both of these stones are now in the Natural History Museum in Washington. Though not important in terms of money, I was, nevertheless, very thrilled with these purchases since they were important for me as a mineral dealer.

|

| The rare borate mineral painite is named for A. C. D. Pain. See Bill Larson’s “Painite Comes to Pala” for more on this coveted material. (Photo: Jeff Scovil) |

I was invited to dinner that night at Mr. Pain’s home and, I must confess, that was the first good meal I had had in Mogok. The cook was very good and a wonderful apple cider, which had a very strong alcoholic content, was served. Mr. Pain told me that he had a constant supply of this cider which he imported from England. He related many legends and a good deal about the history of Burma. It is very difficult to ascertain exactly when Mogok was founded. It was first settled by man about 3000 B.C. indicated by relics of this period used by the Mongolians who were the first settlers. Such relics consisted of stone axes, chisels and many types of spears, stones and arrowheads similar to our Indian stones.

Modern Mogok was founded in 579 A.D. It was all jungle and thick flowers. While hunting in the jungle, head hunters of the Sabwa of Momeik lost their way and slept under a tree.[1] At daybreak they heard birds singing and hovering over them. Investigating the commotion of the birds, they ran into a mountain break full of rubies. They collected as many as they could carry and brought them to the Sabwa of Momeik, who immediately realized the wealth of this area and sent some of his household to establish Mogok. It was first called Thahpainpin Pomegranate for the fruit growing there. The original little village still exists in the extreme west limits of Mogok.

Burma was then ruled by kings. The capital of the kingdom was the city of Ava situated near the present site of Mandalay. When he heard about the fabulous wealth of the Mogok area, the king invaded. An agreement was made by the Sabwa of Momeik with the king establishing Mogok as part of Burma. The Sabwa, in return, received twelve specified villages. It is recorded that this pact was signed in the year 1254.

Mr. Pain told another legend related to him by a very old and wise man of Mogok, who had died at the age of 120. According to this old man, an agent of King Mindin named U Tun Po Hland showed a ruby called the Nga Mauk Ruby to a French trade mission telling them that quantities of such valuable stones were to be found in Mogok. At that time, France controlled Siam and now after seeing this fabulous ruby, wanted to purchase the whole Mogok area from King Mindin. Members of the trade mission were especially impressed when the Nga Mauk Ruby was placed in a pan of water and the water turned red, the color of the ruby. King Mindin flatly refused to sell and contended there was not enough money in the world to buy this fabulous area. The ruby itself is said to have become part of the famous British Crown Jewels. Although there was no description given as to weight, subsequent accounts made it a very large stone and probably the famous one in the Crown Jewels that was tested a few years ago and found to be a spinel.

|

| The Burmese interior minister (in green hat) offering rubies to French officers in Mogok. The large ruby centered is the famous Nga Mauk Ruby used as an index of value. (Image: Saya Saw, School of Saw, 1880s, from the Bill Larson Collection) |

In 1886 the British government occupied the Mogok area after a victorious battle. Major Charles Barnard and his troops took over. He entered the Mogok area via Pyaung Gaung and renamed the village Barnard Village. It is situated eight miles northwest of Mogok.

I thanked Mr. Pain for the wonderful dinner and all the exciting histories of Burma. I told him that I was very proud to be able to participate by purchasing these magnificent gems that had such ancient and wonderful histories. I got up and said goodbye when he asked me to please sit down for another minute as he wanted to tell me just a little more about the foreigners living in Mogok today. I was in no particular hurry and sat down as he asked.

Before he began, he served a glass of very fine cognac which was of old vintage and he told me he had had it for at least twenty years, that he only used it for special guests, and I was flattered that I was one of those for whom he decided to serve it.

We relaxed and sipped our brandy. He began talking again telling me about the other British subjects living in Mogok.

I left Mr. Pain’s, pleased by my purchases, warmed by the cognac and filled with interesting gossip about the “foreigners.”

I was pleased with all of my purchases and with U Khin Maung, and he was pleased with himself and was elated at having become such an efficient broker in such a short time. He was proud of himself and he worked hard searching for valuable, rare jewels even when I was not in Mogok.

I thought of the mildness, the gentle smile, the friendliness and wisdom of all the people I had met in Mogok. I thought of Daw Phon, her son Maung Myint, the rubies and peridots I now owned. I even thought kindly of the insurgents, especially the chief of Pyaung Gaung for the welcome he offered me and for his sincere promise of a swift return to Mogok.

When I told U Khin Maung that it was time for me to return home and asked him, “When can we leave?” he replied to my question with one of his own. “Do you want to leave a large and wonderful lot of star stones behind in all sizes but of the finest quality I have ever seen? We can probably complete this transaction in a day or two and still catch the Friday plane for Rangoon.”

|

| This mine site from the mid-twentieth century employed traditional methods of extraction aided perhaps by some machinery (as suggested by power lines). Fifty years earlier, British mechanization began after a hydroelectric plant was completed in 1898. But such efforts were not without their own challenges, eventually being abandoned, as recounted by Richard Hughes in The Burma Ruby Mines, Ltd. section of his Ruby & Sapphire. (Photo: Martin Ehrmann) |

The fabulous collection he spoke of had taken U Maung Sein two years to acquire. We were on our way to visit him. His home was located on a deserted path not far from where we lived. U Khin Maung stopped to indicate a footpath leading to his house. To my surprise, his cottage was not the typical Mogok type but a very modern English style cottage. It was built on stilts, but on the lower floor was a two-door garage with only a jeep in it and on the other side was a lapidary shop containing a cutting machine. A Burmese cutter sitting with his feet crossed under his body was cutting a gem, operating the wheels with his left hand and grinding the stone with his right. As we passed him he nodded his head and smiled. We climbed the steps leading to the living quarters and were just about to remove our shoes when Sein came out, bade us welcome and asked us to enter. He told us it was not necessary to take our shoes off as we would transact business in his office. The room we entered was about eight feet square and had two windows. A cabinet was standing against one of the walls and against the other was an old dilapidated safe with both a combination lock and a keyhole for a key. In the center of the room was an enameled table with four chairs around it. He motioned us to take seats around the table.

As soon as we were seated, the customary coffee, tin of English cigarettes, and box of English biscuits were placed on the table by his wife. After the coffee, a very nice green tea was served and we were ready to talk business.

U Maung Sein opened the safe and brought out a box which contained about 25 cabochons of various colors. There were star rubies, star sapphires of light and dark shades of blue. Some were gray and others were pink, but they were all of a very uniform fine quality, rarely seen in such stones. They were clean, their color was good, they were unblemished and apparently had good stars. The sizes were small, from two to five carats. It was a bright sunny day and when I brought the boxes into the sunlight, the sharpest defined 6-ray stars appeared on all the stones in the box. They were certainly well selected and of a quality I would not have believed existed.

U Maung Sein noticed how pleased I was and began to bring out the balance of his collection. I counted a total of about 300 stones and he told me their weight was about 1200 carats or less. Several of the star rubies were of the same quality as the one I had bought from Daw Phon, but because of their small sizes, they were on a much lower price level. Our bargaining then began. I asked him the price for the lot but to my surprise and chagrin he closed all boxes suddenly and replaced them in the safe without saying a word. I was just about to ask my agent the meaning of this scene which he was watching fascinated when another man came inside. U Khin Maung introduced him as the partner of U Maung Sein. He acknowledged the introduction and began chatting with Sein in Burmese. Finally he turned to U Khin Maung and spoke to him briefly. His voice seemed strong, firm but very polite. U Khin Maung translated, “I am sorry I couldn’t come sooner. I was delayed by a miner I had some business with. I wanted to be here before we talked business as we are not going to sell the whole collection today. We are interested in selling one or two boxes only, but maybe we will sell four of the eight boxes if you will give us our price.” U Khin Maung told them that I would respect their decision and buy only what they wished to sell.

|

| Ehrmann mentions peridot as among the “rarer gemstones found in the Mogok area.” This 5.75-carat star peridot from Burma measures 10.16 x 8.66 x 7.28 mm. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

Back onto the table came the eight boxes and U Khin Maung asked how much for four boxes. I chose four boxes at random without re-opening and looking at them again. The asking price was $25.00 a carat. I asked my agent to offer them $7.00 and we finally agreed to pay $9.00 and our offer was accepted. I then told U Khin Maung to offer them $12.00 per carat for the whole lot. Through U Khin Maung I told them they would have enough money to start a new collection and in one year, next year when I came back, they would have another collection of the same quality to sell me. But they replied that it would take them more than ten years to make another collection as good. I asked him how long it took to make the collection they had. They admitted it had not taken long but stated that they had been very lucky and had found one area in which most of the stones found were of this gem quality, but that it would be impossible from now on to find stones of this quality and they did not expect to ever have any more. Nonetheless, the price I offered them intrigued them and we concluded the deal. I was happy and they were happy and, of course, U Khin Maung was very happy. He had added up all of his 5% commissions on the purchases I had made and was dreaming of the bonus I would add and he knew that he had done very well.

After we finalized our deal, we left for home to have lunch. At lunch U Khin Maung advised me that we had to make one more visit that day. He had seen a box of spinels of the finest quality and of most unusual colors and he thought I would be very much interested. I was in fact very interested in buying some fine spinels and so I agreed.

That afternoon I learned a lesson I shall never forget. I am glad it happened the way it did because one more mistake like it and I would be barred from purchasing anything in Burma. It was the astuteness of U Khin Maung that saved me.

We took the jeep into Kyatpyin where this dealer lived. We went through the same rituals again before the spinels were brought out for viewing. There were about 30 spinels of very fine quality and color, and the best came in large sizes. Quickly I estimated that $3,000 would be a very fair price for me to pay for this lot. I asked him how much he wanted for the lot. He said $3,000, exactly what I thought they were worth. This was the first and only time in Mogok that I was offered stones at a price I thought they were worth and I was willing to pay. However, that willingness almost cost me my reputation as a gem dealer in Mogok when I immediately agreed to pay his price without further bargaining.

|

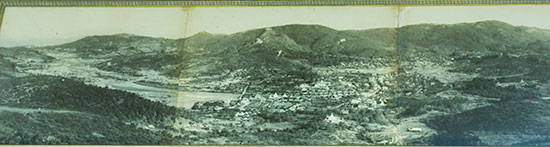

| About 8 km. to the west of Mogok lies Kyatpyin, site of Martin Ehrmann’s near-miss. The photo-collage above was taken circa 1910. Click the image to enlarge. |

I will never forget the expression and change in him at my ready acquiescence. He turned pale and was as white as a sheet. He told my agent I must be a smart one trying to take advantage of a poor simple dealer. He threatened to tell the other dealers that I couldn’t be trusted. I thought fast and pushed the box to the owner immediately and said to my agent that the offer need not be accepted. U Khin Maung then cleverly took the blame saying that he had translated incorrectly, and that when I said $3,000 was okay, I had merely repeated the dealer’s statement of price, that I was not willing to pay that price for these stones. He then whispered to me to make an offer of $1,500, which I did. After the usual bargaining, I bought the spinels for $2,500, $500 less than I was willing to pay and I was absolved of all blame. From then on, I never agreed to anyone on the first price asked. I resolved always to dicker even if I was offered stones at a price I was willing to pay.

U Khin Maung and I discussed this episode again and again. I congratulated him on his quick thinking and told him when he took the blame for the wrong translation, I noticed the natural color slowly returning to the owner of the box of spinels. I told him as we left, let’s celebrate and stop off at the market place and have a Chinese dinner, which I liked better than the Burmese food.

When we returned to U Khin Maung’s house, a message was handed to me which was brought by one of the brokers who had returned to Mogok from Rangoon. The message was from my dealer friend Aung Chi at the Strand Hotel. He had had a phone call from Hemchand Monanhal, my broker in Bombay. They left word that a very important collection of gemstones was being offered for sale by one of the most influential maharajas in all of India. Aung Chi was told that they had made arrangements that I would be the first to look at this collection. The insurgents were still very active on the 28-mile jungle stretch between Mogok and Momeik. There were many military patrols but still there were reports of a few holdups and a kidnapping of a military officer. Apparently, while in command of a group of soldiers, this officer had captured a dozen insurgents and had tied them up in an open truck and paraded them through the city of Mogok; therefore, his kidnapping on his next trip. Daw Phon offered a car to us again for a safe unescorted trip to the airport. Before I left I talked at length to U Khin Maung who was remaining in Mogok.

In Mogok it was absolutely necessary for a foreign buyer to have a broker on whom he could rely to serve as intermediary between the people and himself. Such a man had to have his roots in Mogok. He had to be shrewd, cunning and yet diplomatic. He had to have integrity and good judgment. His loyalty had to be unshakable, for in the buyer’s absence it was the broker who spoke for him. I trust U Khin Maung completely. He was staying a few days longer in Mogok as he had to take care of shipping my purchases and making payments to the people from whom I had purchased things. I gave him instructions to send everything registered airmail to Zurich.

When we finally arrived in Momeik, the airplane from Mandalay and Rangoon was already waiting for its return. The usual contingent of soldiers was on the airfield protecting the passengers and cargos from possible attack from rebels and insurgents. Finally departure time was announced. I said farewell to U Khin Maung and Maung Myint and was soon airborne. I arrived in Rangoon before it was dark and took a taxi to the Strand Hotel where a room was reserved for me. Aung Chi was waiting for me and repeated the complete message to me from Bombay and I made arrangements to fly there the next day.

Before leaving his office, he showed me a very magnificent rough gem diamond weighing about 14 carats. A gem dealer in Rangoon had purchased it and wanted to sell it to me as he couldn’t find a Rangoon buyer. Normally, I did not buy diamonds, polished or rough, but I was impressed with the quality and purity of this beautiful piece of rough. It was really a blue-white stone and quite valuable. It took a few hours of bargaining. The dealer was sitting in the lobby and after many trips back and forth, I bought the diamond.

After a good night’s sleep in Rangoon at the Strand Hotel, I caught the plane the following morning and went on to Bombay. Traditionally, the dealers of India are the most important in the Orient. Perhaps the widespread impression that rubies and sapphires originate in India stems from the fact that most of the gemstones found in Ceylon, Siam and Burma are purchased by Indian dealers who keep in close touch with the gem producing mines. Also there was once a very important sapphire locality in Kashmir which produced gems of the finest quality. Many stones having that fine quality are still called Kashmir sapphires though they actually come from other areas.

The competition in India is very keen because so many engage in this business. Indians also supply the western market via Paris where many gem buyers’ offices are located. Purchasers from all over the world generally find it much more convenient to do their buying in Paris where the Indian dealers keep their outlets well supplied.

Also, during the height of Britain’s power in India, the maharajas were the wealthiest chosen few able to buy the most expensive gems. Each of these maharajas tried to outdo the others in acquiring the most important gems, some valued as high as a million dollars, just as art collectors do in Europe and the United States. Consequently, for a long time, few large gems reached the western market.

The collection I was to see was one of the great collections of one of the most powerful maharajas who decided he wanted to leave India and lead the life of leisure in another country. All this was related to me by Mr. Hemchand who met me at the airport in Bombay and while we were driving to the Taj Mahal Hotel. I informed him that I was very sorry that I couldn’t make any more purchases this trip as I had spent the quota of all my backers and didn’t have very much left. So, if he could postpone the appointment for about six months I would come back and by that time I would have a new supply of money available to make some important purchases. He was to call for me the next morning at 9:00 at the Taj Mahal Hotel to take me to his office.

The office staff was very glad to see me but I told them that I would probably leave the following day and wouldn’t have very much time to look at anything as I had no more money available. But Mr. Hemchand insisted on showing me one gem. He said I probably had never seen anything like it before. When he opened the white paper and took out the egg-shaped star sapphire, I was impressed. It was something I had never seen before. It was a star sapphire the size of a large pigeon egg and weighed over 30 carats. It impressed me so much as it was of a very fine deep blue color and had the finest star on both sides of the egg. It was a very sharp star and my thoughts were immediately that I could probably cut it in half and have two of the very finest star sapphires that I could possibly buy. Mr. Hemchand was more of a European than he was an Indian and his traits were more those of a diamond merchant in Antwerp than that of a gem merchant in Bombay. I had the rough 14-carat diamond with me and I knew he would buy it. I thought perhaps if we could make a trade, that would be the best solution and sure enough we both agreed immediately I was to get the star sapphire and he was to get the diamond. I asked him to hold it for me as I wanted to have it cut in Burma when I got back and I didn’t want to take it to Europe. He put it in his safe and he said it will be waiting for you when you return on your next trip.

I left Bombay for Zurich the following day and, as usual, checked in at the Storchen Hotel, my favorite hotel in Zurich. In Zurich I worked with a wholesale jeweler named Eugster. All merchandise I sent from Burma was addressed to him. I had to wait a week before these shipments began to arrive. Of course, I got in touch with my backers in New York and told them of the wonderful success I had on this trip. Some wanted certain items and they asked me to sell whatever I could in Zurich.

Mr. Edward Gubelin, president of Gubelin’s of Switzerland, with jewelry stores in every important city in Switzerland, was the first one I showed these small gem sapphires, rubies and the various colored star stones I had bought in Mogok. He was very much impressed with them, the same as I was when I saw them and told me he had never seen the quality of star rubies like these. He wished there were a few larger stones among them. He asked me to leave the whole lot with him and he would make a choice. I gave him a lot price and I gave him choice price.

|

| Dr. Edward Gubelin with William Larson and a group of workers at the entrance to the Lin Yuang Chi ruby mine in Mogok, Burma during a 1993 visit. (Photo: Robert E. Kane, courtesy of Fine Gems International) |

After a few days, I called him and he asked me to come over as he was ready. To my surprise, he bought the whole lot. He said he just couldn’t let them go and he already had his designers working on some wonderful designs for these very fine stones. I shipped the desired merchandise to my various backers in New York and shipped the peridots to my office in Los Angeles as I wanted to handle them myself.

I had been on that trip six weeks and it was longer than I wanted to stay away. My family was delighted to see me and I decided that for the next two weeks I would do nothing but relax and enjoy them. I did, however, take the gem crystal peridots to museums in Boston, Philadelphia, New York and Washington, D.C. and all the curators were delighted to get them. Some of the other roughs I had cut and the largest stone I had finished was one weighing over 200 carats which is now in the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., together with the finest gem crystals that ever came out of Mogok.

1. Ehrmann discusses sabwas in Chapter One. Sabwa (aka sawbwa) is the Burmese term for saopha (literally Lord of Heaven), applied to hereditary chiefs of Shan principalities, according to Pinkaew Laungaramsri. (“Women, nation, and the ambivalence of subversive identification along the Thai-Burmese border.” SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 21.1 (2006): 68+. Academic OneFile. Web. 12 May 2011.) In his 1916 book, The King’s Indian Allies: The Rajas and their India, St. Nihal Singh defines sabwa thus: “The Buddhist Rulers of the Burma States bear the title of Sabwa” (p. 148). [return to text]