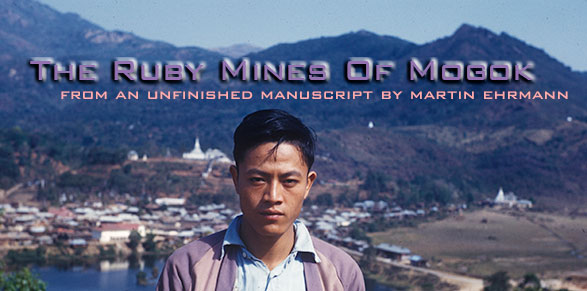

The Ruby Mines of Mogok – Chapter Five, Part Two

This is Burma, and it will be quite

unlike any land you know about…

— Rudyard Kipling, Letters from the East

See also Chapter One, Chapter Two, Chapter Three, Chapter Four, Chapter Five Part One, and Chapter Six.

Chapter Five, Part Two: Mogaung with Dr. Vic Meen

At the close of Chapter Five, Part One, Martin Ehrmann travels north from Momeik roughly 150 miles, to Myitkyina, with his friend Dr. Vic Meen, curator of gems and minerals at the Royal Ontario Museum. They are to visit the jade area surrounding Mogaung, about 50 miles to the northwest of Myitkyina.

This village [of Myitkyina] is in the eastern part of the so-called jade belt and it is close to the border of Hunan Province of Mainland China. We were met by Lee San Cheek, the largest and wealthiest jade producer in Burma. His entourage of co-workers and key personnel came with him to welcome us to northern Burma. Transportation was provided by two trucks. We left for Mogaung about 50 miles northwest of Myitkyina. It is the northernmost city in Burma with a railroad station.

Mogaung is in the center of the jade mining district. The largest deposits of jade are found within a radius of 75 miles in all directions from Mogaung. Arriving there, we stopped at Lee San Cheek’s house where we were to stay while in Mogaung. He gave us the entire left wing of the finest house in Mogaung. It had many bedrooms and many modern baths. We were as comfortable as in any first class hotel that we could possibly find in Burma. After we were settled, Lee San Cheek appeared, took us to another house two streets away. It was getting dark. The moon was just appearing over the colorful mountains when we reached that house and there we were met by the very large family of Lee San Cheek. There must have been at least ten men, fifteen women and thirty or more children. They all chatted away and, of course, we couldn’t understand a word. A few minutes later we were ushered into a dining room together with all of the men of the family. There were about twelve men at dinner.

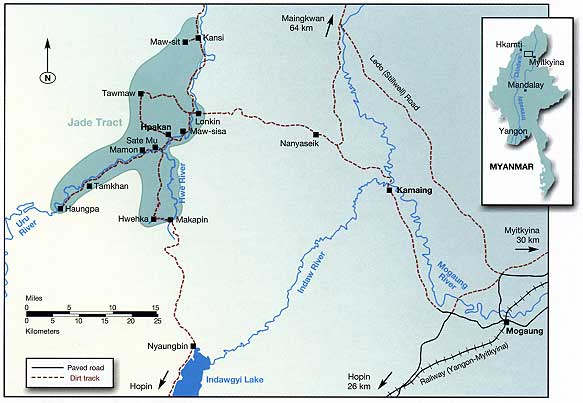

|

| The road to Hpakan leads from Mogaung, the northernmost city in Burma with a railroad station. Map adapted by R.W. Hughes and G. Bosshart from Hind Co. Map (1945); included in “Burmese Jade: The Inscrutable Gem” on Palagems.com. |

Our first meal in Mogaung was a feast and there were to be many more such feasts in the next two weeks. The finest Chinese food was served. It was the Hunan type, different from the type of food we get in the States which is usually Peking, Mandarin, Shanghai or Cantonese style. It was very different, very tasty, but at times a little too spicy for our tastes. Vic took to the chopsticks as if he had never eaten with anything but chopsticks all his life after only a few moments of instruction from one of the men in our party who explained how Chinese food was served, pointing to the fifteen dishes placed in the center of the table and the individual rice bowls given to each of us. He took some meat and chicken out of one of the center bowls, placed the food in his bowl of rice and using his chopsticks, ate it from that bowl. The man sitting next to Vic began placing delicacies on Vic’s bowl and Vic reciprocated. He reached with his chopsticks into the center and selected a piece of chicken and give it to the man and said, “This is for you, this is the Pope’s nose.” Nobody understood him but everybody laughed. The man ate it with great delight. The meal must have lasted about an hour.

After dinner we stepped into the foyer, out of the house and into the garden where they had benches and we all sat down. I had a recorder with me and started recording the voices of the children. They played and sang and I played it back to them. They were thrilled to hear their own voices. Lee San Cheek then dictated a letter to his wife who lived in Hong Kong. He asked me to take it back with me and play it for her when I got back to Hong Kong.

Our first night in Mogaung was very comfortable. The beds were good and we woke up the following morning at around 8:00 and bathed. Downstairs, Lee San Cheek was sitting at the table and just as we came in a big bowl of boiled eggs was brought in. There must have been 30 or 40 eggs in this bowl. Some bread and butter and coffee was also served. After eating two or three eggs, we both quit. Lee San Cheek said no, that is not the way to do it. He kept on eating the eggs as if they were something special. We ate what we could. After our breakfast he took us for a ride through the town of Myitkyina.

|

| “Everyone living in Mogaung is a jade dealer.” Jade boulders languish in the sun before finding a new owner. (Photo: Martin Ehrmann) |

He introduced us to the government jade man in charge of evaluating. Every boulder of jade mined must be evaluated by this man. Then we visited many yards where we saw hundreds of boulders of jade. Lee San Cheek told us that everyone living in Mogaung was a jade dealer. He was very well known there and occasionally he would stop and buy a boulder or two within a very few minutes. Lee San Cheek gave us a brief history of jade mining in Burma. He told us that the jade mines in northern Burma contained the most important deposits of this material in the world. He said the early Chinese prized it greatly and are said to have believed that jade possesses magical qualities which made it a sacred stone. Three thousand years ago jade from this area was brought by caravan to the center of China. Members of the imperial family and the nobility of the Chow dynasty wore ornaments of delicately carved jade. They even buried jade with the dead and believed it would ward off evil spirits. Weapons of war such as swords, sabers, spears and knives were also fashioned from this precious stone.

At a later date the wonderful qualities such as color and durability belonging to jade became known in the Western world and the demand for jade increased greatly.

After a few days in Mogaung, Lee San Cheek took us on a trip to the actual jade deposits. This region is almost inaccessible most of the year. During the monsoon season, it is impossible to reach this highly dissected upland region consisting of ranges of mountains. Our destination was Thaman, one of the principal jade mining districts, which was situated on a plateau 3,000 feet above sea level. The highest mountain is Loi Me, about a mile above sea level. Thaman is about 65 miles from Mogaung. Under the best of conditions the roads there are barely passable. The most satisfactory mode of transportation of the jade was by mule or by ox cart. Lee San Cheek told us that jade mining is in progress only three months of the year, March to May. All mining activities cease with the coming of the rainy season since the shaft and holes fill up with water within a few days.

|

| Cutting the crust. Prospective buyers look for color below the rind. (Photo: Martin Ehrmann) |

The mining methods today are still the same as those used 1,000 years ago except that hydraulic drills are now being used in some areas. Before any jade mining is begun, every worker whether Kachin, Shan, Burman or Chinese prays to the jade spirits called nats in the belief that they thus will be led to discover valuable jade quickly. A foot high fence is built around a small square section in each mining area to ward off the evil spirits. Shrubs and flowers are planted around these squares.

The overburden is quarried with sticks and crowbars until a steep face is obtained. The water is dammed upstream to make it flow over the steep face washing away all earth and leaving the boulders clearly exposed for examination. It is well to remember that the selection of the locality and all the work are started through pure instinct or an inner conviction of the miners rather than any scientific reasons. When valuable jade is discovered in one spot, all the miners flock to it and work it until all the jade has been removed. Consequently, they frequently forget where they had worked last and begin digging in spots previously mined with much time and labor lost. Scientific mapping and coordinating by well organized mining programs would certainly yield much larger amounts of fine jade from this area.

We next went by jeep to Hpakan. The jeep got us there all right but we traveled at a creeping pace.

In Hpakan, we again were housed in a wonderful place with a large family. We each had our own room and the bathing facilities weren’t too bad but the other sanitary facilities were terrible. The food situation was exactly the same as in Mogaung, that is, family cooking in grand style with every meal a feast.

During the next few days Vic and I visited many jade mines and watched the miners work. Again the mines were very conspicuous with that little fence in one corner of the mine and the plants and shrubs in the middle to ward off the evil spirits.

There were many riverbeds which were always scrutinized for small boulders of jade which were often of the finest quality jade found in Burma. During the afternoons we stayed in the house a good deal. Vic played Chinese gin rummy with some of the family. He caught onto their game, which was similar to our gin rummy, very fast, and enjoyed playing, joking and laughing with them.

While planning our trip to the north, I was concerned about Vic’s health. I considered myself an experienced jungle traveler and I thought that I could withstand whatever we would have to face but I was worried about Vic, especially since there would be no medical facilities within a radius of 50 miles from where we would be.

We were pretty far north in Burma, only 100 miles or so from the Tibetan border. We were a few miles from Hpakan where the confluence of Irrawaddy and Chinwin Rivers is. It was a beautiful sunshiny day, rather hot. After looking at the water, we wanted very much to take a swim. We each wore a longyi only and had nothing to use as a swimsuit. There weren’t too many houses around and I thought we could safely bathe in the nude. The water coming from Tibet looked inviting. It was. clear, bright and very fast flowing. Here the water divided into two parts, one going off to the east, making the Irrawaddy River which flowed for over a thousand miles down to Rangoon. The other, the Chinwin River on the other side. We went into a fairly hidden area and took our longyis off and went in swimming. The water was wonderful, cool and delightful. We were swimming up and down and talking to each other and enjoying it when suddenly I got a terrible cramp in my stomach. It came on very suddenly and I excused myself and went to the other shore of the river and relieved myself. I returned to the water but was still not feeling very well. The cramps continued and I told Vic that I had better go home. We dried in the sun for a few minutes, put on our longyis and started off towards home.

That afternoon I began to shiver. I was cold and hot and then cold again. My stomach was aching and every once in a while I had to get up and get relieved. I kept on asking for blankets and more blankets and finally Vic brought me in two bottles of bourbon, Old Grand-Dad, which was served to him on the plane and which he didn’t drink and took with him and kept all this time. He said he was going to make some tea grog with these two and I should drink. I new by then my temperature was up a good deal and I thought it was at least 104 degrees. I had never felt so bad in all my life. Vic prepared the grog, gave me a few aspirins and asked me to cover myself and go to sleep. It was impossible for me to sleep however because I still had chills and fever. We tried to locate a doctor but the only medic that we could ever hope for was a district nurse who was in a place 20 miles away. When she finally arrived she made me as comfortable as she could. She took my temperature which was 105 degrees. She didn’t know what my sickness was and told us the nearest doctor was about 60 miles away and it would be impossible to get him here.

Vic really did take good care of me. During the night, Vic slept close to me and took me, practically carried me, many times during the night to the outhouse. The nurse had left; gave me some herb tea and during the night I drank several cups of it. When I woke in the morning, I felt like a new man. Fortunately, I, the experienced jungle traveler and not Vic the novice, had been struck by this mysterious malady. Who knows what it would have done to the intestines of a traveler who had built up no resistance!

Lee San Cheek thought we would go back to Thaman and drive back to Mogaung and asked me if I was up to it. I said yes, I felt very good and my temperature seemed normal again and I couldn’t understand how a person could be so sick one day and feel so good the following morning. I stood the trip with the jeep very nicely and after seven or eight hours passing Thaman again, we arrived back at Mogaung to our luxurious quarters.

|

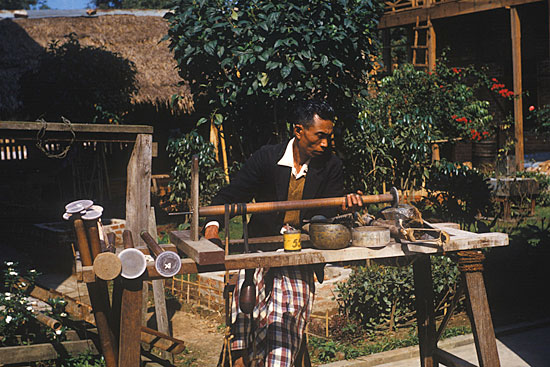

| Saw. Cutting a small jade boulder. (Photo: Martin Ehrmann) |

The next day Lee San Cheek took us to the regional office of the jade evaluation committee, and introduced us to the chief. Actually there is an evaluation committee for every jade mine. When a piece of jade is found, the financier has it evaluated by his committee which receives a fee of 5% of the value. As a rule, such evaluations are very low. If the owner decides to keep the jade, the miners receive half of the evaluated price. Ten percent more goes to the local government under whose jurisdiction the stone is found. Values in these evaluations are never spoken aloud but merely indicated among the interested parties by the conventional finger pressure under a handkerchief. It is costly to ship jade boulders to Mogaung, which was the chief trading center. Sometimes as many as 50 coolies are employed to transport a boulder weighing a ton. They proceed very slowly through the rugged terrain until they reach a place where the jade can be placed on an ox cart and brought to Mogaung. There the government’s chief evaluator again collects the final tax and this is 33 1/3% of the value before the merchant is permitted to ship the jade out of Burma. Up to this point, the value given by the local evaluation committee is really only a fictitious figure, without any actual basis. The main idea is to have as low an evaluation as possible until all government taxes are paid.

Every week a local auction of jade boulders is held. The jades are prepared for the auctions in the following manner. Each boulder is weighed and a seal is placed on it. At a strategic point, a cut of approximately ¾ of an inch in width and a half an inch in depth is made into each boulder, then polished to show the color of the jade. The Chinese jade dealers pride themselves on being able to determine the value of each jade boulder by the appearance of the polished cut. I think they know exactly where the fine green color is and that is where they do the cutting. Actually, it is very much of a gamble to buy jade in this manner and the purchasers are actually gamblers rather than jade experts.

Much money has been lost by these superficial methods of purchasing. At the same time, you can say that much money has been made.

The auctions differ greatly from ours. There is audible competitive bidding. The purchaser accompanies the auctioneer along the path on which the boulders are displayed. A stop is made before each numbered boulder in which the purchaser expresses interest. With his hand and the auctioneer’s hand covered by a cloth, the bidder makes his offer by pressure on the auctioneer’s finger, thus insuring absolute secrecy in each transaction. In the evening the sales are completed and the boulders turned over to the highest bidder. We watched one such auction and both Vic and I couldn’t understand how the auctioneer remembers the names of the buyers and the prices of the 40 or 50 sales he made during that day. Apparently from memory, he knew exactly who bought what and in the evening the material was delivered to the highest bidder.

Of course, not all boulders are sold during these auctions. These boulders that are not sold during these auctions are shipped to dealers in Hong Kong for similar auction sales.

All jades leaving Burma are shipped from Mogaung after clearance by the government agency. They inspect the seals and then inspect the papers that have been made out in Mogaung by the government agency. When satisfied, boulders of jadeites are then wrapped in heavy dark cloth tied with hemp rope and shipped by boat down the Irrawaddy River to Rangoon where they are put on other boats going to Hong Kong. Also at that time a considerable quantity found its way by ox cart across the border to Hunan Province in China.

Prior to the communist takeover in China, jade was shipped to Canton, Shanghai and Peking. Approximately 15% of all jades of the poorest quality remains in Burma and is usually sold in Mandalay where there are many jade cutters and jade jewelry manufacturers.

Vic was interested in purchasing a boulder and with Lee San Cheek’s help, we picked one that were all satisfied with. Vic wanted it sawed in half and polished so that he could display two pieces in his museum.

In Mogaung these boulders are sawed by hand. The saw consists of several bamboo sticks tied together and bent to look like a bow similar to that of a bow and arrow, the end being a wire of a certain thickness. The cutting process is begun by marking the piece where the cut should be. Two men usually handle the saw. A third man feeds the carborundum [abrasive] into the area that has to be cut. Pretty soon the wires are full of carborundum and can cut freely for a period of time before new fluid carborundum—that is, carborundum mixed with oil—is put in its place again, and it is surprising how fast these fellows work. There are three shifts and the work goes on for 24 hours a day and to our surprise, the boulder was sawn completely in three days. Before leaving Mogaung to return to Mogok where we had left some unfinished business, we looked at the boulder again and we were told that the next day the polishing would start and when finished it would be shipped down to Rangoon by the Irrawaddy River and arrive there within five days.

|

| Saw II. Workers saw a large boulder using the method described in the paragraph above. (Photo: Martin Ehrmann) |

While still in Mogaung and with a few days to spare, Vic and I decided to visit the Burmese amber mines. Amber was highly prized by the Chinese even before the beginning of the Christian era. Burmese amber is very different from amber extracted in the Baltic Sea in east Prussia. The Burmese type is a gold color with a beautiful bluish streak through it and is strongly fluorescent, even in ordinary sunlight. It is also pure, harder and tougher than Prussian amber, thus making it excellent material for cutting and carving into figures, snuff bottles, vases and various Chinese carved objects of art. The only other occurrence of amber exhibiting this fluorescent phenomenon of similar quality is found in Sicily.

|

| Raw honey. This 56.94-carat amber contains plant material. It measures 50 x 31 x 14 mm. From the collection of Bill Larson. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

Amber occurs in the lower tertiaries, which consist of finely bedded rockish, blue shale and sandstone, the shales being generally predominant. In some places the two are alternately inter-bedded with a few layers of limestone conglomerate. Sometimes sandstone of various shades of blue and pink are almost laminated and in places contain shaley concretions which vary in diameter from one to several inches. Generally the sandstone in shale bears carbonatious impressions. Sometimes these rocks contain very thin coal seams in which amber is imbedded in the form of concretions. Because of the soft nature of the shale and sandstone, few exposures are seen on the surface.

Vic and I visited several amber mines which are located in the northernmost section of Burma and extend in a straight line to the border of Assam through Myitkyina to the Yunan border. The Hukawang Valley, with the villages of Maingkwan and Kamaung, is the chief source. In most mines, amber occurs in pockets imbedded in blue sandstones or dark blue shale with a fine coal seam. The presence of coal seams is a favorable sign for the occurrence of good amber. Amber usually occurs in the elliptical pieces and occasionally in block-like forms. The best amber is found at a depth of about 35 to 50 feet, very seldom in large rocks. The average size being that of a normal closed fist.

|

| Miró via Myitkyina. If the great Catalan artist had had a Gold Period, he might have sculpted along the lines of this 26.04-carat amber (click to enlarge). It measures 35 x 19 x 14 mm and may have a dewdrop trapped within it. From the collection of Bill Larson. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

The method of mining amber is as primitive as that of mining jade. The mine is a well-like affair about 4 feet square and descends to a maximum depth of approximately 50 feet. Four miners work in each pit. Two dig underground with a hoe. The other two haul up the mass in a rattan basket with a long hooked bamboo rod and examine each basket for amber. The pits are lined with a bamboo barricade which appears flimsily constructed, but does miraculously hold the pit from caving in.

The progress in a pit is very slow. Usually two men dig about two feet a day. All mining is stopped when a hard layer of sand is reached since the miners believe there is no amber beneath the sand. It might prove interesting to sink a few bores much deeper to test their theory. Much of the amber thus mined remains in the area and is made into earrings, bracelets and other popular jewelry worn by the natives of the Hukawang Valley. Chinese merchants, too, purchase great quantities of amber especially the larger pieces which are suitable for carved objects of art. They export these pieces to China where most of the carving is done. Some of this amber also finds its way to the European market.

We returned to Mogok where we had to stay for a few days to make arrangements for our last purchases. As we were about ready to leave for Hong Kong we were informed by U Khin Maung that he had received a message from Lee San Cheek that he had shipped the boulder of jade by air to Hong Kong and it would be waiting there when we arrived at his wife’s place. Lee San Cheek also said that he would be there to welcome us in Hong Kong.

In Hong Kong, we were met at the airport by my friend Dunt King. He and Vic got along very well from the very first. Dunt King was a connoisseur of good food but being a Moslem abstained from pork dishes so whenever he took us to dinner it was always into a Moslem place where he was sure that no pork dishes were served. But the food in the places he took us was wonderful. Shrimp, chicken and meats other than pork were served and the dishes were always selected with great care and were all wonderful. I knew that Hong Kong was one of the best places for Chinese food but I never realized that even the very small places that were hidden in the side streets and were owned by Moslems served wonderful food. Dunt King had reserved a room for us at the Peninsula Hotel which, to my mind, is the finest hotel in the world. Unfortunately they didn’t have a room in the old building which was charming and quite different than the modern new annex where they housed us temporarily.

After two days we were transferred to the old building and Vic pretty soon agreed that my estimation of the Peninsula Hotel that it was the finest hotel and also had the finest service available than any hotel that he had ever been in. He was very pleased with his room and with the hotel generally.

|

| Catch a cab. This 5.20-carat natural jadeite cabochon from Burma exhibits good translucency and its deep green color has just a hint of bluish overtones. It measures 11.6 x 9.27 x 6.1 mm and is available, Inventory #14844. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

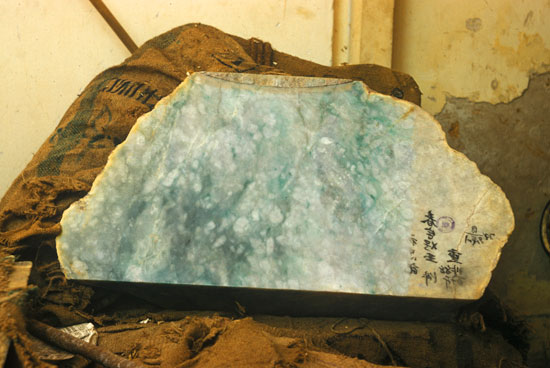

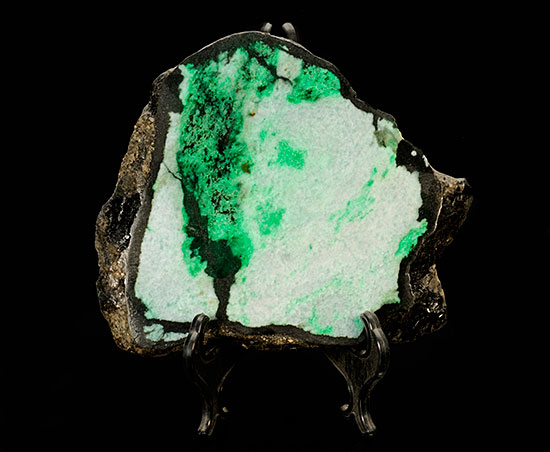

Lee San Cheek arrived in Hong Kong the following day. He invited us to his house. His storeroom at the time was in the Happy Valley section of Hong Kong, near the racetrack. We were both anxious to see the jade which had been sawed and polished in such an unusually short time so that Vic could see it before he left for Toronto. The boulder was in a corner of the storeroom but was covered with several bags so that we couldn’t see the surface. Mrs. Lee San Cheek greeted us with a great big smile and from that smile I knew that we had not done so badly. This hunch was confirmed by the great big smile on the face of the bookkeeper of Lee San Cheek. This was the first time I had ever seen him smile. He was sort of a morose person, didn’t talk very much and certainly didn’t smile often so I had a feeling we were in good shape. The sacks were finally removed and we looked at the two pieces of jade. I could not say that they were the most wonderful quality of jade, but certainly they contained the best colors of jade I had seen in a long time and the variety of colors was amazing. There were some big slashes of mauve, together with several shades of green, from the light green to the very dark green—almost a fine emerald green, and the edges were brownish and yellowish. But the main thing, the distribution was even throughout the boulder making it a very attractive boulder indeed. It was certainly worth the price we had to pay for it without knowing what was on the inside.

|

| Sawn. Bisected boulder reveals delicate coloring. (Photo: Martin Ehrmann) |

I wondered whether Lee San Cheek had known, before the sawing, exactly what it was going to yield and later, when I asked him, he said he had known more or less, but that you can never be sure. That evening Lee San Cheek had arranged a banquet for us and since Dunt King was one of the invited guests, he honored his choice of restaurants and we went to the best Moslem restaurant in Hong Kong and this really was a feast. We had been eating, I believe, more than three hours and when we were finished, we were really finished. During the meal toasts were said by all of us. Vic made a very elaborate speech concerning his trip to the jade mines, which he appreciated so much, the hospitality such as he had never seen anywhere in the world, and the food in the jungle where Lee San Cheek lived. It was a very festive occasion indeed. It was very late when we finished. Lee San Cheek invited us to attend an auction in one of the downtown hotels he was having the following day. I was delighted at the opportunity to see a Hong Kong jade auction which I had missed on my other visits.

Usually my timing was bad and no auctions took place while I was in Hong Kong. The procedure in this auction was exactly the same as in Mogaung, except that the jades were not in boulders but were already sliced, thus the color was already visible. There were a number of smaller boulders and the bidding began the same way as it did in Mogaung. The advantage of an auction sale is that with the secret fingertip bidding, nobody really knows who the highest bidder is and if there were no bids high enough to the liking of the seller, he had the privilege of just not giving it to the highest bidder, so he was always very safe. After this auction was over, I asked Lee San Cheek whether he thought it was a successful one and he said, well, during this session in the afternoon he sold about $120,000 of jade. This was a pretty good day’s work considering the qualities that he sold. Sometimes one piece of jade could be worth much more than the $120,000 paid for this big lot of more than a ton. But this was commercial quality, perhaps a little below.

|

| Sawn II. This sliced jadeite displays a range of green hues. From the collection of Bill Larson. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

The colors varied but certainly they were not real jewel jade. I was really surprised at the high price these jades would bring. In addition to being the biggest jade market in the world, Hong Kong also developed into a terrific wholesale gem market. There were many dealers from India and many from Burma who had moved there. Thai and Ceylonese had opened offices and had their wares for sale. The Japanese seemed to be coming into their own as well. The Japanese liked cat’s eyes, the Americans wanted star sapphires or rubies, the Europeans wanted faceted cut sapphires and rubies and so forth. And according to one of the biggest dealers there, the wholesale market in Hong Kong was really gaining momentum. Dunt King was our guide in Hong Kong and we did some sightseeing. We went all over the island of Victoria and the mainland of Kowloon as far as the Chinese border. Hong Kong is one of the most beautiful sights in the world. When you come in by air or, as you stand on the Kowloon side on high ground, you can see the complete harbor and all the mountains surrounding it. Until recently the airport in Hong Kong, because of the mountains all around, could only be used during their daylight hours. There were no night flights. However, since then a runway has been built into the bay several miles so that all flights anytime, with the proper lights and guidance, can come into Hong Kong. Hong Kong is now one of the busiest airports in the Orient.

We finished our business, said our goodbyes to Lee San Cheek and Dunt King. Vic and I also took our leave of each other as I was going to Calcutta and Bombay and he was going back to Canada. Our planes left on the same day an hour apart and to our surprise, we had quite an entourage waiting for us when we arrived at the airport. Lee San Cheek, his wife, Dunt King and his wife and many of the employees of Lee San Cheek were all there to bid us bon voyage.

This trip to Burma was especially rewarding because of the wonderful mineral specimens I had been able to buy. The peridot crystals, the ruby and sapphire crystals, all of which are very rare in crystallized form and very difficult to obtain. And, of course, the enthusiasm and enjoyment Dr. Vic Meen displayed on being my companion on this wonderful journey. All the curators of our museums knew what I never told my gem associates, that minerals were and still are my first love. I would travel anywhere in the world just to find the right specimen for a particular collection.