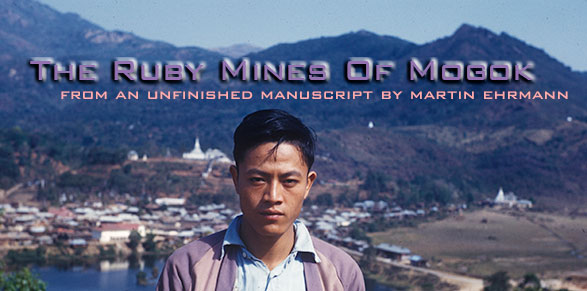

The Ruby Mines of Mogok – Chapter Four

This is Burma, and it will be quite

unlike any land you know about…

— Rudyard Kipling, Letters from the East

See also Chapter One, Chapter Two, Chapter Three, Chapter Five Part One, Chapter Five Part Two, and Chapter Six.

Chapter Four: The King of the Rubies

and the Infamous Gem Sapphire

U Law Si, the Chinese 80-year-old opium smoking mine owner and gem dealer, sent me word to visit him the next morning. I knew from the few transactions I had had with him in the past that his reputation as the toughest dealer in Mogok was accurate. He never sold anything directly to a local dealer, always using one of his favorite brokers who promised never to reveal the source of the merchandise.

Rumors abounded that he had stashed away fabulous gems found by him when he was working for the ruby syndicate some 40 years ago and never delivered to them.

I felt very flattered. We arrived at his home the next morning and enjoyed the usual preliminary social visit.

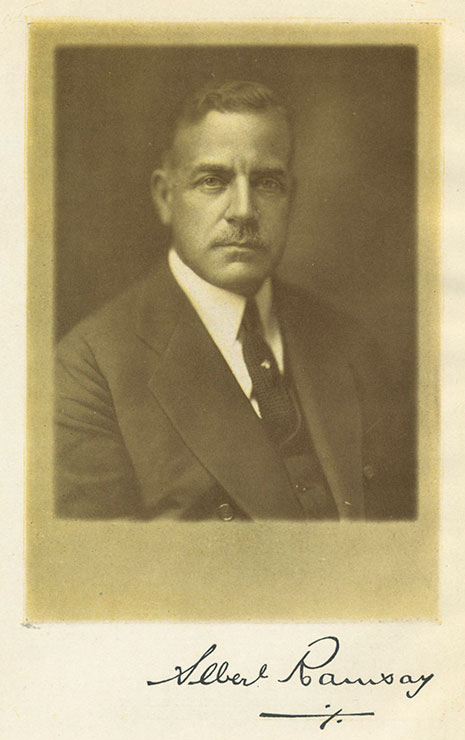

He asked me if I knew Mr. Albert Ramsay and when I told him that I did and that Mr. Ramsay has offices in the same building as mine, U Law Si told me that when he was a young man he worked with Mr. Ramsay and thought very highly of him.

|

| Albert Ramsay and the title page of his In Search of the Precious Stone, 1925. (From the library of Pala International) |

|

“I am glad to know that you are his friend,” he said, “And therefore I feel I can trust you completely.”

He then instructed me to return the following morning, as he wanted to show me the most wonderful gem in existence in the world.

“What kind of a stone?” I curiously inquired. “Come back tomorrow and you will see.”

Both U Khin Maung and I sensed that it was something very important.

I spent a very restless night and couldn’t conceive of what stone would be unveiled the following day. It was hours before I was able to fall asleep.

I was awakened at dawn by the mumbling of the prayers in the village. And upon opening the bedroom door was surprised to find that U Law Si was already waiting for me in his usual corner of the living room. He was engrossed in smoking his opium pipe and I was tempted to ask him if smoking opium all his life had not harmed his health, but decided that it was not the proper time to do so. At that moment he began cleaning his pipe and extracting the residue of the opium with a scoop. All through this operation, a breeze swept through the room and interfered with his relighting of the pipe.

He slowly arose and it was clear that he carried his 80 years very well. He was rather tall for a Chinese—about 5'10"—very thin and lanky, but stood very straight for his years. His four visible upper teeth were as black as his three lowers.

U Law Si told my agent that he had taken a liking to me and that I had always conducted myself like a gentleman and therefore he had chosen me to be the one to buy this magnificent gem. He stated that he was certain that I would do the best for him and would keep its source a secret. He continued rambling on about his early days in Mogok working for the company in many capacities; how he remembered Albert Ramsay; and that because of his age, he decided to turn this fabulous gem into cash and divide the proceeds among his children and grandchildren prior to his death.

He came to me and placed the gem into my open hand.

He had given me a magnificent rough ruby weighing approximately 300 carats with one corner completely flawless.

I had never before seen such a magnificent gem. However, I was able to refrain from any exclamations, but only because of my prior experience throughout the world in seeing famous and fabulous gems and treasures in the many countries I had visited, but I said to myself, “This is the most fantastic and most beautiful gem I have ever held in my hands.”

“Where did you get it?” I asked. U Law Si never answered. I kept on studying the stone from all angles, took it out from the dark room into the sunlight and estimated that more than half, if not two-thirds of the gem was flawless and that it would cut into a large and unusual size gem.

Mogok customs required that the seller quote a price for the stone to open negotiations. I therefore asked U Law Si, “How much are you asking for this magnificent gem?” His reply was matter-of-factly, “Five million dollars.”

I looked at him in amazement. Since it was just as much of a tradition to immediately give a counter offer, I said, “Two hundred fifty thousand dollars.”

He smiled and looked at me very kindly and said, “Young man, we are too far apart.” He retook the gem into his hands and looked at it with admiration. “This gem lives,” he said. “There will never be another like it. How much longer will you be in, Mogok this trip?” as he returned the gem to me.

After I told him that I expected to be in Mogok for two more weeks, he told me to keep the gem with me and to study it carefully and that he was sure I would reconsider my offer. If we don’t come to an agreement, you can return it to me before you leave.” I knew he was serious, so I took the stone, placed it in my pocket and left.

Back in my quarters, I took the stone out and studied it for a long time. I could not keep from glancing at U Khin Maung , who was sifting some gem gravel he had brought in that morning. Not once did he ask me to let him hold the stone or even make any remarks about the stone.

“What are you so busy with that gravel for?” I asked. “Wouldn’t you rather look at the gem than play with the gravel?”

“I certainly would,” he said, “but you seem so busy with it I didn’t want to disturb you and this gives me something to do.”

|

| Sorting it out. Workers and buyers examine mining gravels in mid-century Mogok. (Photo: Martin Ehrmann) |

I handed him the ruby and asked him to weigh it for me.

He returned the stone, stating that it weighed 285 carats and informed me that he thought that at least 190 carats were perfect.

I told him I thought it would cut into a perfect gem of 120 carats and I could see that he agreed with me.

Mogok has a population of approximately twenty gem brokers, each with his own merchandise and problems as to source of supply and source of sales.

Soon after we had returned from U Law Sits, a few of these brokers arrived unannounced at the front steps of our house and told U Khin Maung that they wished to see me on a very confidential matter.

U Khin Maung brought the first one in, who immediately began to tell me about a fabulous ruby that a friend of his had access to and that since he was the best friend of this broker, that this broker was the only one in Mogok who could handle the deal.

As I interviewed each of the other brokers one by one, they all said substantially the same story. During these interviews, I had the gem in my pocket but never let them know.

I could never find out how all of the brokers had found out about the gem, especially since U Law Si wanted it kept secret—but they knew.

During the next few days I examined the stone at least fifteen to twenty times per day and suddenly felt that I couldn’t look at any other gemstone. My mind was constantly occupied with the ruby that I still had in my possession.

As my time to leave Mogok approached, I had to make an important decision about the gem. I thought very seriously about asking U Law Si to give me the stone on an approval basis and allow me to try to sell it for him for a commission of 10%. However, I realized that if he had refused this suggestion, I would never see the stone again.

I had also learned, the hard way, that perseverance and patience between a buyer and seller usually made the difference in Mogok in the final transaction. I therefore decided to use these tactics in dealing with U Law Si. I knew the Burmese were masters in patience, but I decided that I would try to be more patient and to outdo the masters.

I visited U Law Si and informed him that I was planning on leaving Mogok the next day and asked him what would be the eventual destination of this fabulous stone.

He asked if I had reconsidered my offer and I told him that I had not and that I thought my offer was a fair one, but asked, “What is your final price?”

He smiled and finally said, “One million dollars is a very fair price for such an unusual gem.”

I assured him that I respected his knowledge of the value of gems but I didn’t know of anyone who would take a chance paying one million dollars for a rough stone without being sure of the size of the gem when cut and polished and of the color of the stone after cutting. With that I returned the stone to him.

He took it back and smilingly said, “Let’s wait and see. We don’t have to finalize the transaction now. I assure you that no one but you will buy this gem. I am very happy with your decision and that my thoughts coincide with yours.” We shook hands all around and left.

Later, U Khin Maung informed me that the goods we had purchased were on the way to Rangoon. I felt a great deal of satisfaction in the realization that I was finally ready to leave Mogok with nearly all the merchandise I desired. But at the same time, I felt sad to have to leave the people I had learned to love and respect. We said goodbye to all our friends, dealers, and brokers; to Mr. Pain and Mr. Schiff, and left for Rangoon the following day. I stayed in Rangoon a few more days and visited the Indian surgeon and his sister again. She said that the European buyers had not acquired the large sapphire. She gave me a price she had on this stone and I patiently explained to her that the stone needed a complete re-cutting with much loss of weight. However, she refused my offer. Upon arriving in Zurich I phoned my Paris associates about the big ruby I had seen. I described it in great detail and gave them a rough estimate as to my opinion of its eventual yield. They thought that the offer which I had made was a good one and hoped that I would he able to acquire the ruby at that price and indicated that if the stone was a good as I had described it, they wanted it.

My wife and I returned home to Los Angeles shortly thereafter and rented a furnished apartment in Beverly Hills and a few weeks later I opened a new office in Los Angeles and was back in the gem and mineral business.

A short time later, the mailman delivered a registered package to me and upon opening it and finding the Mogok ruby, all of the excitement of my original view of the stone returned. There was no note—only the stone itself. I determined, from the postmark that the package had been mailed from the University branch of the Palo Alto, California, post office, but the sender’s name and address were illegible. Reacting instinctively to this unexpected treasure, I sent it to my Paris associates that same day by registered air mail.

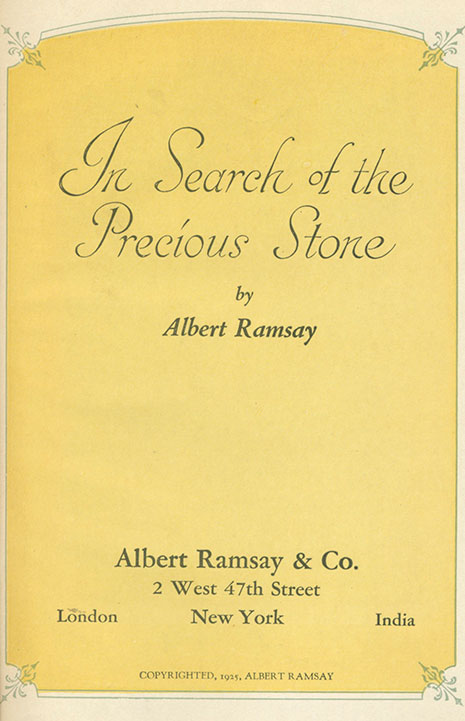

|

| Rough and cut. Illustrations and descriptions of star sapphire, left, and cat’s eye, included in Ramsay’s book. (From the library of Pala International) |

On Saturday of that week, I was in my office to check the mail when the phone rang. The voice on the other end excitedly asked, without any preliminary greeting, “What happened? Did you buy it? It’s better than you described!”

I finally had a chance to explain how I had received the stone and that I still had received no further information about it. I was advised from Paris that there were five partners, four of them putting up a quarter of the cost, with me Sharing in one fifth of the profits. I was authorized to offer up to $300,000 or more if necessary, and with my assurance that I would let them know as soon as I heard, our conversation ended.

“Why,” I asked myself, ”Why did the Mogok dealer, send me the stone? How did it get to California? Who sent it tome? How do I find out?” The more I asked myself these questions, the more my peace of mind was disturbed. I considered sending a cable to Burma, but decided against it for obvious reasons. If the sender wanted to keep the transportation secret, who was I to interfere with his desire?

After an agonizing three weeks, I finally received a person-to-person phone call. After I had identified myself, a shrill voice on the other end of the line, which I recognized immediately as Burmese, asked me if I had received the package. When I replied, “Yes,” and asked why I hadn’t heard from the sender, he explained that he was a grand-nephew of U Law Si, and that he was a student in Palo Alto in political sciences, but had been spending all of his time improving his English and had not had time to call.

I asked him what instructions he had received from his grand-uncle.

“My great uncle will now accept $500,000, which he thinks is a reasonable price, and which will give you a chance to make a decent profit.”

I instinctively counter-offered $300,000 and told him to advise his great-uncle that this was my last and final counteroffer and if not accepted within a month, I would return the stone to any address given to me. He told me he would let me know as soon as possible.

At that time, the Burmese kyat had an official exchange rate of 4.77 to the U.S. dollar, but the black market fluctuation was between 10 to 12 kyats per U.S. dollar. Therefore, all Burmese transactions are in U.S. dollars, English pounds or Swiss francs.

Three weeks later, I finally received confirmation of the acceptance of my $300,000 offer with instructions to send an equivalent amount of English pounds to a bank in London and U.S. dollars to three different banks in Switzerland. I assured U Law Si’s great-nephew that it would be taken care of within a few days, and that was the last time I ever heard from or of him.

I called my associates in Paris and gave them the good news and the instructions on how and where to deposit the funds. I was advised by them that the money would be deposited the following day.

After another three weeks, I heard from my associates that the cutting had been completed and that the final cut weight of the stone was 117 carats—very close to my 120-carat prediction. I was also told that the color was near pigeon’s blood but missed by a hair being the finest color, but that the slight defect in color was more than compensated by the size of the stone. They further opined that by re-cutting, the color and shape could be improved. Apparently there was still a considerable amount of silk and a few flaws which they felt could be eliminated by cutting the stone down to approximately 100 carats.

I waited for a return call from Paris for some time and finally my patience was exhausted and I placed a call to my associates, who advised me that they were just about to give me the good news—the re-cutting had been completed and the stone weighed 99 carats and 99 points and was undoubtedly the finest ruby in the world. [1]

There is no historic proof of a larger faceted ruby in existence. There are many cabochon rubies of larger size, but no such faceted gems.

My associate advised me that I would not have an opportunity of seeing the stone inasmuch as a substantial dealer had followed the progress of the stone and knew exactly when it was going to be finished and had a buyer for it. My curiosity prompted me to ask who the buyer was, but I was informed that he preferred to remain anonymous. All I was told was that he was a big industrialist from Italy and that the gem was to be a present to an institution, which also preferred secrecy. With that we ended our conversation.

With the most important purchase of my career behind me, my only thoughts were to relax and take it easy for the next few months in Los Angeles. However, shortly after my return to Los Angeles, a cable arrived from Bee Frazer, who owned the finest jewelry store in Bangkok. Mrs. Frazer was a native Thai, who had married a very wealthy retired Englishman, but who unfortunately had an incurably rare disease.

The cable simply stated that a rare and expensive gem collection had become available and asked me to return immediately. There were no other details given. As usual, I had to confer with my financiers and was given the go-ahead without further questions being asked.

I arrived in Bangkok dreaming of the wonderful gems I was about to see. As usual, the jewels were of the finest quality and very expensive, but consisted mostly of diamonds of large sizes, in which I was not then interested. Furthermore, the competition from important diamond dealers from India, France, England and Switzerland was great and they were much more familiar than I with this type of material. I therefore showed no interest in this transaction, but decided to return to Mogok. I sent a cable to U Khin Maung, who met me in Momeik, and that same afternoon I was back in Mogok.

U Khin Maung’s mother, who was also very much interested in making a commission from an occasional sale, had made arrangements for one of the important woman dealers to show me some of her fine gems. She told me that Daw Thwe was loaded with some of the best gems in Mogok. (Daw is the female equivalent of the male U in Burmese names. Daw means Madame and U means Mister.)

Next morning, U Khin Maung and his mother took me to Daw Thwe’s house. She was a widow and lived with her two unmarried daughters and her nephew, Kyan Yan, who acted as her broker. Daw Thwe joined us in her living room and her daughter served coffee, English biscuits, and English cigarettes. I watched Daw Thwe and never observed any affection between her and her children, nor any display of any degree of relationship with Kyan Yan, but one felt an unmistakably strong bond between them. Kyan Yan acted as our interpreter.

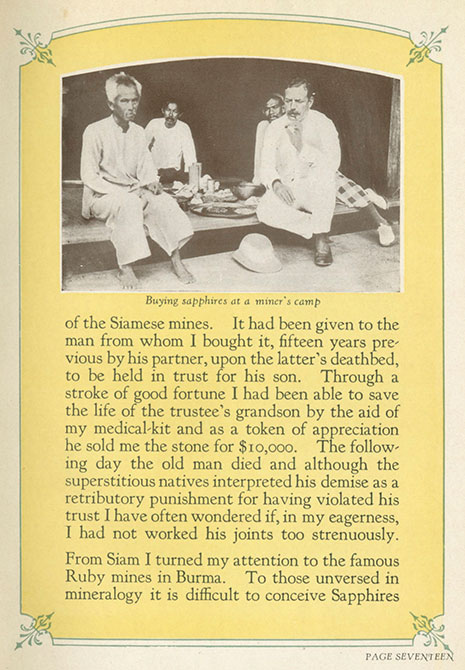

|

| Albert Ramsay buys sapphires at a miner’s camp, included in Ramsay’s book. (From the library of Pala International) |

Daw Thwe left the room and returned with a packet of white paper much larger than the usual gem paper. She placed the packet on the bamboo mat in front of me and asked me to open it. I did and saw the first rough gem sapphire in Mogok. I was quite surprised and realized what an important gem it was. I tried to avoid showing any emotion, and began my examination, which lasted for a long time. The top of the rough was clean, but there were a few flaws on the side, but the clean portion was more than one third of the whole. I knew it would, cut into a large stone—a pear shape perhaps. The center was flawed and I considered that part a total loss, but the bottom part had a fine clear area. I asked permission to take it out in order to examine it in the daylight, and did so. The color was of the finest blue—the most desirable color in sapphires. When I brought it back into the room, I looked at it under the light and what I saw was quite pleasing. Looking through the side, the stone became purple, indicating that after cutting, it would be of the finest Kashmir color.

I asked Daw Thwe its weight and Kyan Yan told me it weighed exactly 1,090 carats. I finally asked Kyan Yan, “How much?” He was silent at first and suddenly he picked up the sapphire and re-examined it, perhaps for the hundredth time. He then spoke clearly end precisely, “$150,000 U.S. dollars.” I turned to U Khin Maung and asked him to step outside with me. He had learned a good deal since he started brokering for me, but I relied more on his native instinct than his knowledge. He called my attention to the fact that it turned purple under artificial light. “As far as I am concerned, I would offer $10,000 for it,” I said. On a hunch I would double that amount, but my offer of $20,000 was refused by both Daw Thwe and Kyan Yan with the usual, “Quare, quare,”—too far apart. In my five years of dealing in Mogok, I had learned what that precious word, “patience,” meant, so I merely indicated that the stone was quite flawed and it was difficult to determine what percentage of gem quality material it would yield.

Kyan Yan picked up the sapphire again.

Daw Thwe’s face didn’t show her feelings about the offer I made. I suggested we come back the next day, giving us both time to think about it. She apparently knew from her experience that I wanted the stone and that I was going to buy it, and she agreed that we might return late the following afternoon.

The next afternoon we did return and Kyan Yan greeted us as we removed our shoes. He was exuberantly friendly. Daw Thwe entered the room and brought the sapphire with her and held it up so I could have a full view of it.

“You can see how difficult it is for me to part with this beautiful gem,” she said with feeling. “If I can’t get my price, I’ll have it cut myself.”

I tried to change the subject tactfully and explained to her how difficult it was for me to deal in gemstones in Mogok, in that every purchase of mine was merely a guesswork on my part as to how the stone would cut, while the seller knew exactly what price the gem would eventually bring. I then asked her her real price for the stone and she replied, “$40,000.” I frankly told her that I wanted to own this gem very much, but I couldn’t pay more than $30,000, which she accepted and our negotiations were completed.

It was at this time that U Khin Maung told me that he was ready to return to Rangoon, and that all merchandise had already been shipped ahead. Because of the obvious risks involved, he never told anyone how this was accomplished.

In Rangoon, we took a taxi to the Strand Hotel and made reservations for the next flight to Zurich. I then called New York, but was unable to get through, so sent a cable to New York to Eddie, stating, “Meet me in Zurich. Sapphire shipped by registered air mail. Will arrive Storche Hotel Wednesday. Martin.”

Eddie saw the gem sapphire for the first time on Friday, immediately after its arrival from Rangoon. My broker brought it to the hotel and I asked him, “Do you like it?” “It’s beautiful,” said my broker, “There aren’t many like it.”

Prior to purchasing the stone, I had contacted Eddie, who was then president of one of the leading gem wholesalers in New York. He agreed to pay for the stone and to divide the profits between us on a fifty-fifty basis.

When we finally met in his room, we had a long greeting and discussion concerning my trip in general. I had known Eddie since 1929, when I first went into the gem and mineral business, and we have been very good friends since then. He had originally worked for a German gem cutter by the name of William V. Schmidt, whose business was primarily synthetic stones. Upon Mr. Schmidt’s death, Eddie purchased the business from the estate and became one of the most successful gem dealers of his generation, and he built one of the finest gem houses in the United States.

I very slowly and deliberately took the stone out and handed it to him, and asked him how he liked it.

His reply shocked me. He said, “Frankly, I don’t think very much of it.”

He kept on looking at the stone and finally told me, “Martin, you made a very bad buy on this stone. I am convinced that because of its many flaws, its yield after cutting is going to be very small and it will be purple, and not blue.”

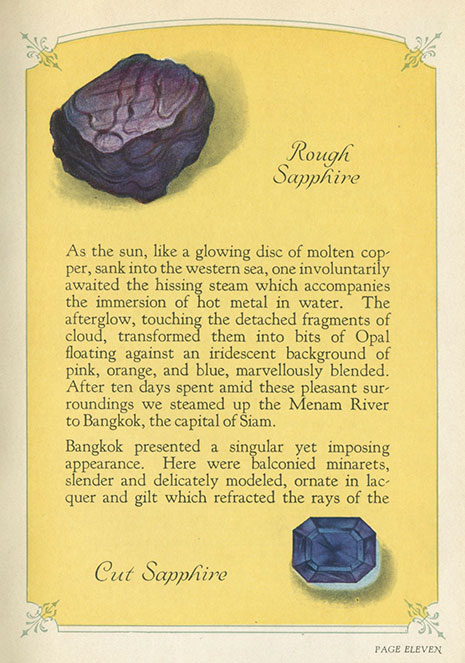

|

| Rough and cut sapphire, included in Ramsay’s book. (From the library of Pala International) |

Although I had known Eddie for many years and always thought that he was a great gem expert, I suddenly, came to the realization that perhaps he was not as knowledgeable as I had thought. He apparently had little knowledge of rough, as opposed to cut gems.

In the trade, it is well known that all Burmese sapphires show a purplish tint when viewed from the side and that stones possessing this phenomena will cut into the finest blue color.

“Martin, we are going to lose money on this stone,” he continued. “You overpaid for it.”

I told him, “Eddie, I’m sorry you feel that way about it, I don’t want you to lose; the responsibility is mine; I can pay you half the money right now and the balance will be paid in two weeks. I will take all the responsibility and you won’t lose a cent.”

He refused my offer, indicating that he would remain my partner on the stone—win or lose.

I asked him, “Eddie, supposing I can sell the stone right her in Zurich at a decent profit? Do you have any objection to that?”

“Go ahead and sell it, if you can,” he replied.

The prospect of my visiting an old friend in the gem business in Zurich pleased me. The taxi took me to his office, unannounced, ten minutes later. He was obviously as glad to see me. I knew exactly how to handle the situation. I showed him the sapphire and explained my predicament. I watched him closely for the next few minutes as he examined the sapphire. Finally he told me that he had seen similar stones often in the past and had only the best results with them. “Tell Eddie that I offered $40,000,” he said. “We will be fifty-fifty partners and I’ll cut it right here,” he continued. “The stone is flawless on top and suitable for a pear shape of about 70 carats. The color will be the best in other areas below the center. We will cut several stones of 20 carats—mostly emerald cuts—but we will also have a few ovals and cushion shapes,” he concluded. “I am happy to be a partner.”

I returned to the hotel and saw Eddie in the corner of the lobby, surrounded by several gem dealers. They were obviously discussing a big deal and I didn’t want to disturb him, so I discreetly walked through the door to the elevator and went to my room and asked the porter to tell Eddie that I would like to see him when he was free.

Some time later, Eddie phoned me to meet him in the lobby, and I was surprised to see that he was not alone. As I approached him, he introduced me to a gem dealer from Geneva. I told Eddie that I was happy to report that I had sold the stone for $40,000.

He stared at me for a minute or so, and at last found the words he was looking for.

“I decided not to sell it here. I want to take it back to the States.”

I was aghast “With your blessings I sold the stone and it will be very embarrassing to renege on the deal,” I told him.

“I don’t care how you do it, but I don’t want to sell the stone,” he replied.

I must have inherited an inordinate amount of patience from my Burmese friends. I realized that the situation with Eddie was hopeless and knowing my Swiss friend as a level-headed, straight and forward man, I decided to approach him with my problem and explained the precise facts. He told me that he understood and that he would absolve me from our oral agreement and suggested that next time I come directly to him.

I returned the stone to Eddie and he shipped it off that afternoon and left for New York the following day.

That afternoon, I went to my broker’s office and we spent the rest of the day with business details and determining which merchandise to retain for offering in Europe and which merchandise to ship to the United States, and shortly thereafter I returned to New York.

The following week, I visited Eddie in his New York office. The receptionist informed me that he wasn’t expected back until later that afternoon, so I walked through to greet some of my old friends. I chatted with one of the best salesmen in the organization and then Eddie joined us and asked me to meet with him and his chief cutter. The cutter was almost 80 years old and I had known him for at least 20 of those years. He had the big sapphire in his hands and his hands were shaking. He again echoed Eddie’s sentiments about the flaws, color and final yield, but upon my insistence, Eddie promised to cut the stone.

I went through the cutting process with Eddie and the cutter, marked the top of the sapphire for the pear shape, but told him to saw it in the center right through the dents and, flawed part, and to clean the lower end by grinding away the flaws. I didn’t want to lose any of the gem material and they agreed to cut it exactly according to my instructions and I left.

I then visited the American Museum of Natural History, which selected some rough ruby and sapphire specimens I had acquired, and a large peridot crystal, with which they were particularly pleased. I then journeyed to Washington, D.C., and the Smithsonian Institute, which selected the largest rough peridot that I had purchased, together with other roughs. I sent that peridot crystal together with other peridots that I had to Gerhard

Becker in Idar-Oberstein, Germany, who is one of the finest cutters I have ever met, and instructed him to cut the peridots and return them to me in Los Angeles when completed.

|

| Burmese sapphire. The specimen, from the collection of Bill Larson, is 3.5 cm. tall. The cut stone is 3.05 cts. Pala Inventory #13690, untreated. (Photo: Wimon Manorotkul) |

Upon my arrival in Los Angeles, I found awaiting me all of the material that I had shipped and immediately made an appointment with the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History to display to them the items I thought might be interesting. At 10:00 o’clock on Monday, I met with the Director of the Museum, Dr. Friedman, the chief curator, Dr. Downs, the curator, Dr. Gaal, his assistant, Barbara Lowe, and Doug McDonald, the head of the acquisition committee. I had arranged a very artistic display and their choice was unanimous. All fifteen specimens were selected and a memorandum listing the specimens was prepared, and I carefully packed and delivered them.

The balance of the minerals was soon sold to a few dealers without any difficulty.

The following Wednesday, I received a note from Saul in New York, which spoke for itself. It was a clipping from the New York Times, which stated: “World’s largest sapphire takes shape here.”

It further stated that this gem was named the “Queen of Burma” and had been purchased by a Mr. Esmerian, who was a supplier of many gems to the famous jeweler Cartier on Fifth Avenue in New York. Mr. Esmerian was quoted as stating that a pear shape of the finest color would be cut, weighing 65 carats, and many others would be cut from this 1,090 carat rough sapphire. [2]

I have always shied away from publicity of any kind and have always found that when gems or minerals were publicized as worth millions of dollars, they were generally worth only thousands. The experts knew, but the general public believed what it read in the newspapers. Another problem with [news articles] was that they always found their way back to Burma and caused prices to take astronomical jumps, and as a matter of fact, on my next trip to Burma, I found that this New York Times [article] had been read there and it caused me no end of difficulty and embarrassment. [3]

Upon reading the [article], I decided it was necessary for me to go to New York and talk to Eddie in person, and find out what kind of a deal he had made with Mr. Esmerian. If the [article] was at all accurate, my share should have been large.

I called New York and told him that I was coming into New York the following afternoon, and he told me that he would expect me.

Arriving at his office, I told Eddie that I gathered he did very well with the sapphire and asked him what he got for it.

“I got cold feet cutting it, and sold it for $40,000.”

“Don’t you think I should have been consulted?” I asked. “After all, I am your partner! I would have given you that $10,000 profit myself and you knew it.”

With that, he handed me a $5,000 check and said, “This is your profit. Take it.”

I reminded him about my offer in Switzerland and asked him why he didn’t sell it then, but he indicated he would rather not discuss the subject any further. Despite my annoyance at his attitude, I said nothing more about it. I had no doubts that he had actually sold it for only $40,000, but could never understand why.

At last, he asked me, “When are you going to Burma again? Are you still going to buy gems for me?”

I liked Eddie. I always enjoyed his company and felt that without a doubt he felt the same about me. It was therefore very difficult to tell him that as far as I was concerned, I had no intention of going into any further business deals with him.

I reminded him that the publicity was probably going to cost me dearly on my next trip to Burma, but despite it all, I left and we parted as friends.

I didn’t see Eddie for many years, until one day I ran into him in a restaurant. He came over to my table and said:

“Martin, you are proud. I haven’t seen you in a long time. Why?”

“Don’t you really know?” I said.

“No. I can’t think of a good reason.”

“Let’s keep it that way,” I replied.

“Come on up and see me whenever you can,” he said. I never did.

The foregoing are but a few experiences gleaned during my wanderings into distant lands, not only that I might obtain the jewels, but that I might also sense the thrill which comes from searching them out in nature’s hiding-places. To me a gem is not merely a cold, inanimate bauble. It symbolizes years of somebody’s life consecrated to obtaining it; it is moist with the sweat of labor amid untold perils and under tropic sun; it is warm with the lifeblood of its discoverer, and as I hold it upon the palm of my hand, I can again feel the pulse of the man leap as it must have done when he first beheld the fruit of his toil. Can you blame me for being fascinated?

—Albert Ramsay, conclusion to

In Search of the Precious Stone

1. The whereabouts of this ruby are unknown to Pala’s many friends in the trade, thus we would welcome any light that could be shed. Perhaps the stone was recut once again? It can only be speculated to be the most valuable of all rubies we know of. [return to text]

2. “World’s Largest Faultless Sapphire Takes Shape Here,” The New York Times, 21 Januray 1956, p. 23. The article refers to “Raph” (Raphael) Esmerian (father of jeweler and Americana collector Ralph Esmerian who pleaded guilty to fraud on April 15, 2011). The article actually attributes ownership of the Queen of Burma to Cartier, Inc., not Esmerian, who is identified only as having cut the stone, thus the article is written after, not prior to, the cutting. [return to text]

3. For the record, the article states, “The regal Cartier gem, it was understood, will be priced at ‘well over $100,000.’” [return to text]