The Ruby Mines of Mogok – Chapter Three

This is Burma, and it will be quite

unlike any land you know about…

— Rudyard Kipling, Letters from the East

See also Chapter One, Chapter Two, Chapter Four, Chapter Five Part One, Chapter Five Part Two, and Chapter Six.

Chapter Three: The Gems of the Maharajas

and the Sapphires of Mogok

|

| Martin Ehrmann, in a pre-1956 portrait by Bushnell Photo Studio, Los Angeles. (See this note.) |

After having sold most of the gems from my last very successful buying expedition back to Burma I [made] a stopover in Bombay. I had with me new travel money, the assurance of my backers, and the knowledge of their complete confidence in my purchasing ability.

I had cabled Hemchand Monanhal, my agent, to make arrangements with the Maharaja for the following day as my stay in India was to be a very short one. Mr. Hemchand met me at the airport with his private car and driver, a bearded turbaned sheik. First we drove to the Taj Mahal Hotel where I just checked in.

It was late afternoon when we drove to the offices of Hemchand Monanhal. They were located on the fourth floor of a walkup building. It was quite an adventure to walk the four flights. The wooden dilapidated stairway had a landing on each floor with corridors leading in all directions. There were about three hundred people on each floor. The odors were obnoxious and of all varieties including that of cooking. Naked children were running about everywhere. Sari-clad women in the corridors were busily engaged in cooking and selling food items, such as rice, all kinds of spices and nuts. Hemp and cotton were visible in open sacks, bins and a variety of other containers. Each floor seemed like a marketplace. When we reached the fourth floor of the building, its character suddenly changed. The corridors themselves were the same but empty. Several entrances to offices became visible with name plates and type of business printed on the entrance doors. We entered the door marked Hemchand Monanhal, Diamond Merchants. Mr. Monanhal greeted me with a welcome smile and said, “We were waiting for you, Mr. Ehrmann.” I answered, “Glad to be back in Bombay.”

The collection I was about to see was one of the finest gem collections in India belonging to one of the most powerful maharajas, who had decided to leave India to live in Europe for political reasons. Arrangements were made for me to see his collection the following day.

I had never seen such an array of large gemstones—emeralds up to 60 carats of the finest quality and numerous rubies and sapphires in large sizes. There were many old pieces of antique jewelry set with diamonds and the finest Indian antique emerald jewelry. The jewelry consisted of necklaces, bracelets, earrings and rings, all of which were over 200 years old and had been produced by the very famous Indian goldsmiths of the 18th century. I was also shown a magnificent pear shaped diamond weighing about 73 carats, of the finest quality and surely one of the old riverstones from India. Also a very fine 52-carat star sapphire cabochon which had a very beautiful sky blue color, and a magnificent star interested me very much.

|

| Sky blue star. This blue star sapphire from Mogok weighs 17.66 carats, and measures 15 x 11.85 x 9.92 mm. From the Harris Gemstone Collection, a 173-stone collection assembled over nearly twelve years. This sapphire is available, Inventory #18527. (Photo: Mia Dixon) |

I told Hemchand that to purchase such beautiful and expensive material was beyond my authority. I suggested that he get in touch with my backers to either come by themselves if interested or send someone more familiar with the prices and of such fine gems.

My only interest was in the 52-carat star sapphire. I asked Hemchand to bid for it and we were finally successful in buying this piece I wanted so badly. I enjoyed looking at fine gems and was excited when I could find something that would fit into one of my favorite museums. I was always eager to acquire such gems even without any sort of profit. As for myself, the making of money on gemstones was never an important factor but since I was always under obligation to others, the people who paid my expenses and financed me, profit was necessarily an important factor. It was for that reason that I passed the buck on to my financiers regarding this fabulous collection.

I returned to the offices where I was to look at merchandise for the rest of the day. Brokers had been notified that a buyer would be there. Upon arriving, we found that there had been an unannounced raid by the fiscal authorities of Bombay. Such raids were frequent, very secret, and without benefit of search warrants. Usually in such raids all merchandise found and all books were taken to the fiscal office.

These raids were due to the unstable money conditions in the Orient and the wide difference between the official rate and the rate of exchange that could be obtained in the ubiquitous black market. Gems were sold only for stable currency such as dollars, English pounds or Swiss francs. Gem merchants were required to keep accurate records of all exports and of all monies received from sales of gems so that the law requiring exchange by the official bank of India only could be enforced.

Although a particular raid would be against only 10 to 15 dealers, all gem business in Bombay would come to a standstill for at least a week while the dealers took a “vacation” until things got back to normal.

I was actually glad of the turn of events which would give me more time in Burma for my third trip there in one and a half years. I cabled U Khin Maung to meet me in Momeik via next Friday’s plane, bade farewell to my Bombay agents, collected the 32-carat egg-shaped star sapphire and left on the next morning’s plane for Rangoon.

As the plane soared over the Indian landscapes, I was thinking about Mogok, especially about Prince, the little mongrel dog I had picked up on one of Mogok’s streets during my last trip. Because the Buddhist religion forbids taking of life, as many dogs as people inhabit the town of Mogok. Nobody cares for these dogs and they scrounge for food wherever they can. I named my mongrel after Princess, the sister of my agent. In exchange for a bicycle I bought her, she took care of him, fed him, bathed him and kept him in good health. She kept him in an enclosure built by her father under her house and he learned to sleep in a basket within the cage.

To my surprise when I arrived in Rangoon U Khin Maung was there smiling most attractively showing his large white teeth. “Welcome back to Burma, Mr. Ehrmann,” he said. “I thought you would meet me in Momeik tomorrow? Why are you here?” I asked. “Do you remember the story about the fabulous 220-carat sapphire I told you about before you left?” he asked. How could I ever forget! “Is it in Rangoon? When can I see it?” I questioned him. He told me that it was now owned by the most famous surgeon in Rangoon, an Indian who was born in Rangoon. His sister was a gem dealer and we had an appointment to see the gem early that afternoon and that was why he was in Rangoon instead of on his way to Momeik.

We had just time enough for a nice Chinese luncheon before our appointment. During our meal he told me that three of the leading European gem merchants were arriving soon to look at this gem, but that we would be the first to see it. Finally we took a taxi to a very luxurious villa on Prome Road.

The doctor and his sister were waiting for us. We had a few Scotch and sodas and talked amiably about world affairs. From time to time the Doctor asked me about my business affairs. I told him candidly that I worked for several wealthy gem merchants and could spend unlimited amounts for the right merchandise. He nodded to his sister and she left the room. Her movements were very graceful and it was pleasant to watch her.

The Doctor got up and asked us to follow him. We found ourselves in an enclosed patio with dozens of exotic plants, flowers, and a very strong scent of jasmine. We sat around a wrought iron, glass-topped table with four chairs to match. As soon as we were seated the sister came in with four leather covered jewel boxes of even size which she placed on the table. From out of her pocket she took a small box which contained the sapphire and handed it to her brother.

The sapphire was disappointing. The color was fair but the cutting was typically oriental, that is, cut for weight and not for beauty. I quickly estimated that after a complete recutting, we could expect a stone of about 150 carats—not a gem, but of good commercial quality. During my examination I was being watched very closely for signs of approval or disapproval. Casually, I replaced the sapphire in its box and said, “I’ll look at it again when I return from Mogok.” “There is no hurry,” said the Doctor. But his smile was gone. Graciously he told me that he had to leave for the hospital. He invited me to come back anytime. Before he left, he motioned to his sister to take over. The other boxes contained cut peridots, spinels of various color and sizes, small sapphires and rubies, garnets, amethysts and various other rather ordinary semi-precious stones.

I purchased the spinels and peridots quickly as we had no difficulty agreeing on price. The others were of no interest to me. As if by afterthought, I asked the price of the sapphire, but her evasive answer was, “Why don’t we discuss it again when you return to Rangoon.”

|

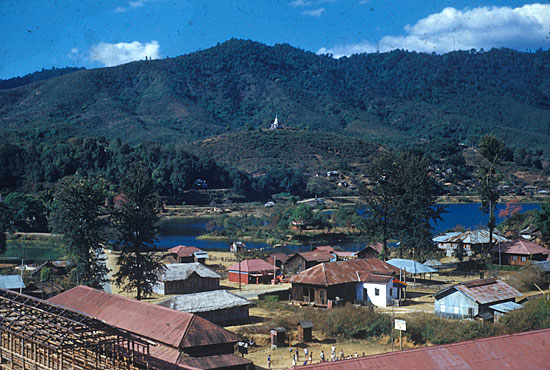

| Than and now. Mogok in 1910, above. Mogok today, below. Click images to enlarge. (From the library of Pala International) |

|

The next day U Khin Maung and I took the plane to Mogok and he took me to his house. As we were about to go to our quarters, he said, “I want you to go in the back and have a look.” Out back I found a complete outhouse building in the place where formerly there was only a sort of bamboo shield over the slit trench. I opened the door of the outhouse and there, right over the slit trench, a crudely built throne had been erected. U Khin Maung was standing right behind me grinning and beaming. I turned around and said to him, “Not as comfortable as the Strand Hotel, but a great improvement. Thank you very much. Let me try it out.” So I sat on it and to my chargrin my feet didn’t reach the ground but were dangling in the middle of this high throne. It was built so high that it was actually more uncomfortable to use than it had been without it. However, I didn’t say anything and we walked out. The big surprise was still to come. When we got into my living room, which also served as my bedroom, I noticed at the side where the concrete wall was, there was a structure built with wooden planks of teakwood about six feet high and about eight feet long, the length of the wall. The depth was exactly 12 inches and I couldn't figure out what it was except that through the window on the side, a new water pipe with a very primitive showerhead had been installed. I asked him what this damn thing was and he said, “This is your bathtub.” And I said, “How am I going to take a bath?” He said, “Well, we’ll heat the water and we will put it in there and you can go in there and bathe and then after you’re through bathing you can shower.” Of oourse what he meant by bathing is that I would wash myself standing up. What he had failed to realize was to fill this contraption to any height would take about 50 to 75, maybe 100 gallons of water which would have been impossible to heat on the little charcoal stoves they used for heating. However, that evening I wanted to take a bath anyway and I asked him to have some water heated. They heated about 5 or 6 pails of water and by the time we poured it into the tub the water was only about up to my shins. I thought it would take the whole night to fill it up any further so I said, “No, that’s all right, U Khin Maung. I will go in and take a bath the way it is.” In order to enter this “bathtub” I had to step on my chair and climb in. The water was warm and nice and slowly I started soaping and finally decided., oh, what the heck, I might as well sit down. I sat down which was all right at first; I just fitted in although it was very tight.

However, ten minutes later, the teakwood began to expand. By the time I was ready to get up it was impossible. It seemed that the harder I tried, the tighter the fit became and I started laughing until my laugh turned into hysteria. Nobody seemed to be in the room and nobody seemed to hear me. Finally I heard U Khin Maung. “What are you laughing about?” he asked. “Look, I am sitting down in the bottom trying to get up and I can’t,” I called. He said, “Oh, all right, I will help you.” In the meantime Prince caught my hysteria and began barking and barking. U Khin MaUng then stood on the chair, leaned over, pulled, but it was impossible to budge me that way so without any warning there he was, standing behind me. He put his arms under my shoulders and tried to lift me up, but slipped and he was then sitting behind me. U Khin Maung was short and stocky. He had a waistline of at least 44 inches and his backside must have been twice the size of mine and there we were, both stuck and both laughing hysterically. I couldn’t move, neither could he. In the meantime, little Prince, still barking, began jumping and finally succeeded in joining us in the “tub” which only added to my problem because now I had to hold him up to protect him from drowning.

We must have been sitting there at least 20 minutes when we heard U Khin Maung’s younger brothers come in. When they discovered our predicament, first they laughed, too. Then they tqok Prince out and then finally with the help of some ropes they succeeded in getting me and then U Khin Maung out. Though we were still laughing, he said, “Well, this thing will have to go". And the next morning my beautiful bathtub was dismantled, and I had to bathe under the pumps again. However, I had become somewhat adept at it and no longer heard the titters from the various houses in the neighborhood as I had previously. I knew that they had gotten used to a foreigner bathing the native way under a pump.

|

| Somewhere in Mogok there is a nearly new teak tub in need of a new home. (Photo: Martin Ehrmann) |

The next day I showed my pigeon egg-size star sapphire [mentioned in Chapter Two] to various experts and asked them how to cut it. It was a little over 32 carats. The advice of most of them was more or less the same. There was only one saw that could do the sawing and it should be cut so as to make one stone of about 12 carats and one of 17 or 18 carats, depending on the loss after sawing. The small one would be from the side of much finer quality and would make a very fine gem. After much discussion we went to the sawer. He was an elderly gentleman who did practically all the sawing of sapphires and rubies for the mine owners and cutters. We walked into his room and there was a saw. It was an upright affair with foot pedals on the bottom of the stand which operated a wheel about the height of my eyes. It looked very primitive but I thought it would be efficient enough until I had a look at the blade. It looked very thick and I blurted out, “Don’t you have a thinner blade than that? There is going to be a great loss cutting it with this!” But he said that that was the only blade he had and that he had never cut a finished stone before. All the sawing he had ever done was of rough material where a carat or two more or less didn’t matter. I said that in that case I would not let him do it, but he asked me to wait and he began to file the edges of the blade on both sides.

It took him about an hour or so to get this job done. When I looked at it again he asked me if I was satisfied. I was sweating but I thought, well, the blade at this point was good enough, and he had enough diamond powder to recharge it. He took the stone and marked it up to my liking. Afraid to watch, I walked out and started talking to U Khin Maung. “Gee, I hope he does all right because all the responsibility rests with me and not with him.” U Khin Maung assured me that he was a good sawer. I lit a cigarette and waited, but I had taken only three or four puffs when the old man came out smiling and in each hand he held a very beautiful star sapphire. The smaller one weighing 12 carats was the most beautiful star sapphire I had ever seen and the other one was also a very fine stone. I was very satisfied with my exchange at this point and was happy with the two stones, especially with the 12-carat stone which, to my mind, was the most beautiful star sapphire then in existence.

Then two very important events took place. The first one was the purchase of a very important rough sapphire which was in the hands of U Law Si, a mine owner from whom I was thereafter to buy many very important gemstones. He was an old Chinese-Burmese, lived in a very large house and whenever we entered we found him sitting on a bamboo mat in a corner of a large room smoking his opium pipe. Over the years, through his many grandchildren, I became his friend. Apparently he had watched me periodically when I came into his house as I played and talked with the children. I like children and the grandchildren of this old man were very attractive and very friendly and I had no difficulty making very fast friends with them.

On that first meeting, after the customary coffee and tea he finally got up from his corner, went into a room next door and brought out a very large piece of rough sapphire. It wasn’t gemmy but rather it was one of those that looked as if it might cut into some very fine star sapphires. After much dickering I finally bought this 2800-carat piece of rough. U Khin Maung and I left immediately as I was very excited and anxious to find our just what I had purchased. We went to our old friend the sawer and he cut off the top piece. This piece I then took to a cutter who started fashioning it into a cabochon. However, it turned out to be very disappointing. There was absolutely no star, it was just plain cabochon material. I had paid quite a price for this piece and of course my disappointment was very great as I had looked forward to a great loss on it. However, such losses are a risk of the business. It wasn’t a complete loss, however, because good cabochon sapphires also have much value, depending, of course, on the quality.

During any visit to Mogok, I was never the only purchaser of gems in town. A. C. D. Paine lived there all year round and Julius Schiff, who worked for a Paris concern, stayed there 8 or 9 months of the year. And in addition to that, there were many Indian dealers who had little cubbyhole offices and regularly purchased stones. There was always gossip about what was purcbased each day. Everybody knew what everybody else bought and sold. No matter how much you wanted to keep your purchases secret, through the grapevie everything became known within a very short time. So it was no secret that I had purchased this big piece of sapphire and that I was terribly disappointed because it did not have the star quality I had hoped for. They also knew the price I’d paid and that same morning I was visited by an Indian dealer asking me if I wanted to sell this piece of rough as he could use it to fill an order he had for cabochons. After the usual bargaining, I sold it to him for half the price I had paid for it. I was glad to get that much out of it as cabochon sapphires at that time did not look very promising to me for the market in the United. States or Europe.

The next day U Khin Maung and I went back to my old Chinese friend. By this time he was also told exactly what had happened but during the course of our conversation I assured him that I didn’t blame him a bit and that it was my own fault. After all, the buyer must beware, and if I made a mistake, it was not his fault but rather my own mistake. I asked him, “Since you know all about it, perhaps in your cubbyhole you might find another piece that will really make some fine star sapphires as I really do need some very fine star sapphires for the united States.” He told me that he had absolutely nothing else and I seemed resigned to the fact that he was not going to do anything about my loss. Our conversation turned to other matters.

We talked about the children, we talked about his family and suddenly he said, “You know, I would like to build another pagoda. I have a Buddhist priest that needs a home and this pagoda is going to be one of the finest ones in this area. Maybe I will find something. Wait just a minute.” He got up from the floor, put his opium pipe down and went into his cubbyhole. A few minutes later he came back with another piece of sapphire, the same color and a little smaller and said, “I guarantee—and I did not guarantee the other one but this one I guarantee—that it will make very fine star sapphires.” He then taught me something very important I’d never known before. He placed a small drop of oil on the top side of the sapphire and then took a light and beamed it on the oil. A beautiful six-sided star became visible. He told me, “This is exactly how the star in these stones will be.” The price he asked for this one was, of course, twice as much as the other but I told him, “Look, even though it wasn’t your fault you know I have taken a big loss. At least give me a chance to make up.” We finally agreed on a price and I bought it. This time I wasn’t really worried...much. I had confidence in the old man’s knowledge of such matters and I knew he had cut many such pieces in his lifetime. I also felt that he was being honest with me.

Off again we went to our sawer who cut off one piece and said, “Oh, this is going to be entirely different from the other. This will make a real fine star sapphire.” We took it to the cutter and we started cutting the cabochon and a few hours later I held a star sapphire weighing over 20 carats in my hand; a very beautiful dark blue color and a very beautiful, sharp star. By the time the cutting was finished I had so many star stones that we later were able to realize a profit in spite of the original loss. We took the stones to Switzerland and sold them all within a few weeks. After that purchase, the brokers, mine owners and dealers became aware of me as an important buyer. They began coming to my quarters in large numbers, unannounced throughout the daylight hours. Through U Khin Maung I let it be known that I would look at merchandise from seven in the morning until about noon. In the afternoons, if we had no appointments to visit dealers or owners, vie would visit any of the 1200 mines in the Mogok area where gems are found in the gem gravels.

|

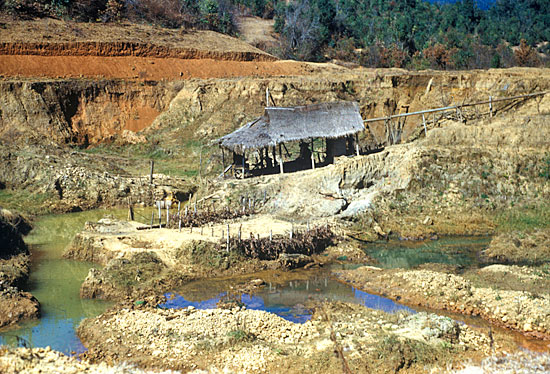

| Than and now. Water is essential to Mogok mining. Above, the end of the line, mid-20th century, in this slide from Martin Ehrmann’s collection. Below, Pala International’s Will Larson stands with workers who have washed gem gravels in the manner described by Ehrmann. (Photos: Martin Ehrmann, above; Bill Larson, below) |

|

There are two types of mining operations. After signs of gem stones having been discovered in an area, the top layer of sand, sometimes as deep as 15 feet, is removed until the gem gravels become visible and then the real work begins. Depending upon the size of the area, from 3 to 25 miners begin to loosen the gem gravel. The large boulders are discarded and the smaller gravel is gradually shoved with shovels and picks into a pile in a concentrated corner. In most mines around Mogok, the water is plentiful. A centrifugal pumping system is used to pump the gravel up to a high point in an 8-inch pipe. A wooden structure able to hold 30 to 40 tons receives all of the gravel. At a specified time of the day the gravels are washed in the following manner. The men who had loosened the gravel come up into the structure and remove the largest pebbles by hand. The balance is pushed through wire mesh to the first level, then to the second level and finally to the bottom. Thus, the large pieces are held on the first level, the smaller pieces on the second, and the smallest pieces on the third and bottom level. At this point the washing operation actually begins. This is a top secret operation. Only the mine owner and his miners are present during this final step. No one is supposed to learn what luck the mine had on any day. The gravels on the lowest level are then taken out in wire baskets and thoroughly washed again. Many pebbles are removed by hand and the balance is carried by each miner to a picking table, 4 by 8 feet in size. The mine owner and his assistants stand there moving the gravels with a metal blade in one hand. The other hand is used to pick out all gems which are then placed in a bamboo container while the other gravels are pushed off the table. This bamboo container is usually tied on to a corner of the table and though I watched this operation many times, I was never able to see what was put in that container. The material that is pushed off the table still contains small pieces of rubies, sapphires and other gems with which the mine owner does not think it worthwhile to bother. This material is gathered into piles which are sold to the poor women relatives of the mine owner. After purchasing one or two piles for a very small amount of money, these women combed them all for remaining gems. If by some chance the mine owner had overlooked a large gem it belongs to the worman purchaser who finds it in her pile. Naturally the results of any washing can be joyous or very disappointing. The entire operation is a rapid one and the results are quickly seen. The process just described is used by all of the mine owners in this area. In Kathe and Kyat Pin, the first six miles, the latter 8 miles from Mogok, there are many individually owned mines employing from five to fifty miners. There are also large tracts of land. These are operated individually by miners who work a designated area by the hole digging method. This is usually a two-man operation. They dig square wells with depths up to about 50 feet. To prevent the walls from caving in the miners shore them with bamboo rods. After the hole is secure the mining process begins. These square holes are no more than one foot in diameter. One of the miners goes down holding on to the shoring and letting himself down to the bottom of the hole. Then the basket is lowered and he fills it with gravel which his associate hauls up.

These visits to the mining areas also gave me an idea of the geology of the area. Rubies and associated minerals such as spinels are formed in a matrix of white dolermatic granular limestone. These rocks have been altered by contact with molten igenous material which crystalizes the calcium carbonate as pure calside, while the impurities became the rubies, spinels and other minerals. Rubies are now seldom found in this matrix. All mining is in the adjacent alluvial ground.

|

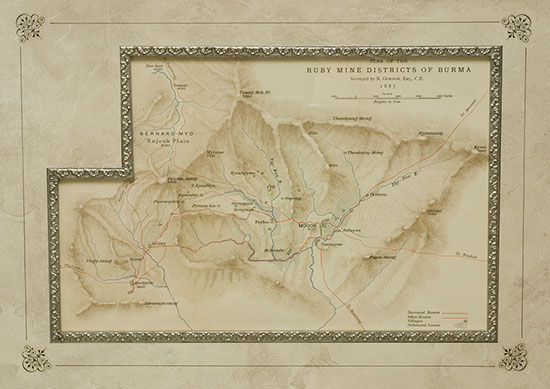

| Ruby Mine Districts of Burma. Click to enlarge. (From the library of Pala International) |

I also learned that the origin of the Mogok gem area had not been described anywhere as there has been no scientific investigation to date. My own superficial observation indicates at least 250 mineral species in the area. It is safe to say that the Mogok area gems are of metamorphic origin. The original rock in which these gems were found is intergraded on the earth’s surface. Loose disintergraded soil was formed in which the gem minerals such as rubies, sapphires and spinels which are not harmed by water and other atmospheric conditions were embedded and remained in excellent condition. This disintergradion was washed away by waters and the gems were washed along as well. Eventually the water stopped flowing and the gravels remained covered by the sand layers of from five to fifteen feet where they now lie waiting to be discovered. Areas are opened daily where new finds are continually being made.

Rubies are khown to occur in three important tracts in upper Burma. But our original source of the gems is found to be highly crystalized limestone. The variety of minerals found in these mines is great. Statistics as to how much these mines yield annually in dollars and cents is usually kept secret. However, U Nyunt Maung, a jovial Burmese and owner of the largest mine in Mogok, told me that about 75,000 carats of rubies and sapphires are mined in the area yearly. Of unusual interest is the fact that only 1% of spinels come from his own mine. These rubies and sapphires are not all of gem quality. A good guess would be that less than 5% of the 75,000 carats is of decent quality and only half of 1% is of gem quality. The varieties of gemstones found there are danburite, scapolite, beryl, zircon, amethyst and fibrolite. In addition many varieties of iron and rare earth minerals occur such as monazite, columbite and tantalite. The danburite found there are from colorless to a dark yellow weighing up to 40 carats. The scapolite cat’s eyes are in white, pink and blue of various sizes up to 50 carats. Apatite are in blue and green as well as the chatoyant variety, which is rather common there. Albite cat’s eyes up to 50 carats are also found in abundance. In Sakhangy, 15 miles from Mogok, there are several decomposed pegmatites in which topazes, orthoclase and other varieties of feldspar are found, as well as tourmaline. Some of the other mines, especially those in Kyat Pin, have kornerupines, sphenes, diopsides, iolites, chrysoberyls and zircon. Mr. Paine has recently found a new species which has been described by the British Museum of Natural History of London as painite.

|

| Edwin W. Streeter. (From the library of Pala International) |

In 1889 the Ruby Mine Company Syndicate Limited was formed, capitalized by numerous English bankers and industrialists. It was handled by the management firm of Streeter & Company in London. According to agreement, this company paid the British Crown 40,000 rupees yearly plus one-sixth of all profits accumulated. Barrington Brow, M.P., was sent from England to negotiate the first five-year contract, which expired in 1895. Scientific mining began and several geologists were sent to survey the Mogok area. They reported that the bulk of the gem-bearing gravel was located in the center of town where most of the natives lived. The company negotiated with the owners of these properties and bought all the huts located in the surveyed gem-bearing bed. The natives were given new homes or, where possible, old homes were moved to new localities hacked out of the nearby jungles. These moves presented no problem since the natives were well compensated and were promised employment. Mining began immediately after the people were moved. Electricity was brought to Mogok with the construction of a power plant. Digging began and several millions of dollars of rubies, sapphires, spinels and other gems were mined. A single ruby of fabulous size reportedly worth one million dollars, was discovered. Profits were good under the first contract. The company and townspeople were happy with the new way of life. The first contract had expired and in 1896 the company negotiated again with the British Government and agreed to pay a tax of 3,150,000 kyats, about 800,000 dollars, plus one-fifth of the total profits for 14 years. This contract included all the mines within a radius of 10 miles of Mogok. These were the boom days with everyone working and much money in circulation.

|

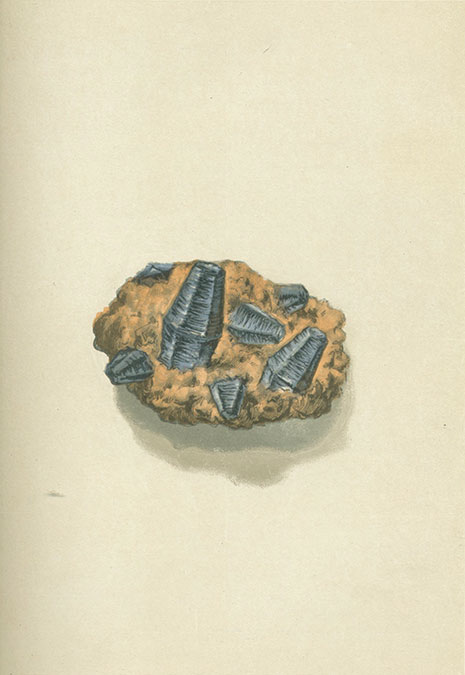

| Sapphire in the Matrix, an illustration included in Edwin W. Streeter’s Precious Stones and Gems, 5th edition, 1892. (From the library of Pala International) |

In 1906 the company extended its mining operation to other areas and bought all the property in the city limits of Mogok, again moving homes to new sites. Today the original Mogok area is the site of a beautiful lake in the center of town. In that year a 42-carat, fine pigeon-blood ruby was found. After cutting the ruby weighed 22 carats. It was purchased by an Indian gem dealer, M. Chodilla, for 300,000 kyats, over $100,000.

Because of heavy rainfall and much excavating, pumping became a serious problem. In the rainy season the hole would fill and stop all mining operations. Experts from London solved the water problem by building tunnels for the water to flow off from the hole. However, this proved to be only a temporary solution. Tunnels costing $200,000 were built into the mountains. After a year the same problem arose.

|

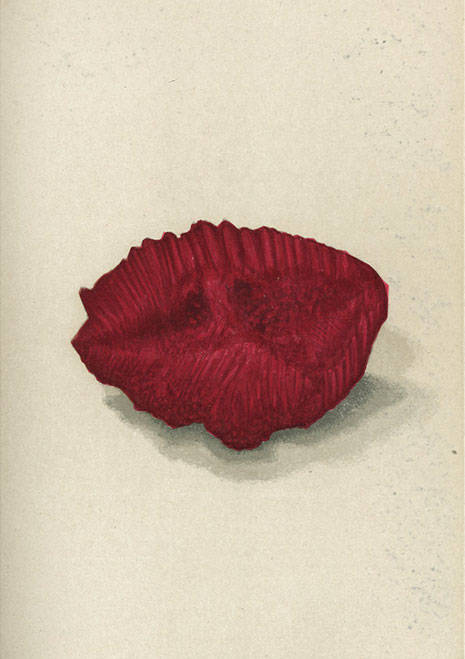

| Burma Ruby, weight 1184 carats, an illustration included in Edwin W. Streeter’s Precious Stones and Gems, 5th edition, 1892. (From the library of Pala International) |

In 1914 affairs of the Company began changing rapidly for the worse. Because of much stealing, technical problems, and wide extensions, large sums of money were lost. There was no security possible in such a vast area of operation. But they continued working until 1922, the expiration date of the contract, which marked cessation of company operation. Some personnel remained until 1928 working privately with local people on a half-share basis. On August 28, 1928, this group attempted to remove water from the big tunnels in order to empty the big hole. That venture culminated in disaster as the mountainside caved in. Nevertheless, gem mining continued.

I had taken offices in Rockefeller Center in the International Building, 630 Fifth Avenue, when the Building Center was first opened. On the same floor on the other side of the building there was a dealer by the name of Albert Ramsay, a gem dealer who came to Mogok at the beginning of World War I. He was a wonderful lapidary. His alert and inventive mind eventually made him the savior of the mining industry in Mogok. In previous years only the clear rubies, sapphires and spinels had been sawed. Such stones were not too plentiful, especially those of faceting quality. Mr. Ramsay began experimenting with the translucent varieties of rubies and sapphires and found that by cutting certain of the crystals with the base perpendicular to the crystal axis, a star was formed. Heretofore such material had been ignored as having no market value. After his discovery of the star, Mr. Ramsay began buying all the material he could obtain and which he cut into cabochons showing wonderful stars. It took him a long time to convince the jewelers of Europe and America that this type of stone would gain favor with the gem-loving public. But he finally succeeded and mining was revived in Mogok. Ramsay remained in Burma until 1930 when he moved back to England and a few years later came to the United States. Before he left he bought the largest rough gem sapphire for which he paid $30,000. According to his story, 32 stones were cut from it, one of which was sold for the total amount paid for the original rough stone.

|

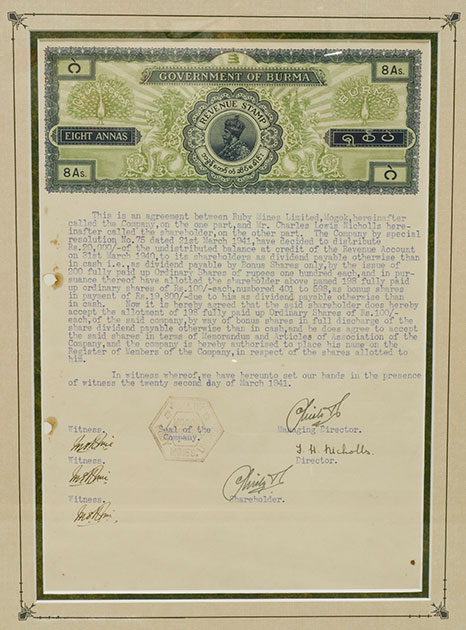

| Ruby Mines Limited, Mogok, shares issued to Charles Lewis Nicholls, March 22, 1941. Click to enlarge. (From the library of Pala International) |

Homesteading of mines began in 1950. Because of pressure from the local people, rules and regulations were made. Claims were made by individuals and granted by the Crown. The tax levy was ten rupees per miner employed. By this time all company holdings had been abolished and the machinery and electric plant were sold to a Mr. Morgan and Mr. Nicholls. Mr. Morgan has since died but Mr. Nicholls still lives, is married to a native Burmese and still carries on supplying electricity to the whole area. During the day electricity is supplied by him to all the mines in the area. At night it is supplied for all the homes and as far as I could learn, his rates were cheaper than any of the government operated companies in Burma.

On May 7, 1942, Mogok was invaded by the Japanese and all official mining stopped. But secretly some mining continued and under the watchful eyes of the Japanese many fine gems were recovered during the war years.

|