|

California Gem Mining:

Chronicle of a Comeback

By David Federman

Reprinted from Modern Jeweler, September 1991

In the early 1900s San Diego County was a cornucopia of gems. In recent years, top-notch finds have helped restore the region’s splendor.

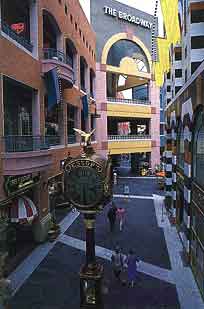

The post cards don’t do it justice. But the street clock at Horton Plaza in downtown San Diego is nonetheless a landmark. Jeweled with gems from Southern California—including tourmaline, topaz and agate—it is “the most visible monument to San Diego’s gem mining history,” says author John Sinkankas, who runs Peri Lithon Books, a local mail-order house that specializes in hard-to-find volumes on gems.

But rarely do any of the hundreds of locals who meet every day at the 21-foot clock know that it is the greatest reminder of the glory years between 1890 and 1912 when their hometown was a major gem mining, cutting and exporting center. Built by one of San Diego’s most famous jewelers, Joseph Jessop, founder of J. Jessop Sons, the clock was a culmination of and tribute to California’s gem-rush days when it was installed in 1907.

|

| The street clock at Horton Plaza in downtown San Diego, adorned with tourmaline, agate and other Southern California gems, is a symbol of the region’s rich mining history. |

Locals can be excused for their ignorance of the days when area prospectors were as content to find precious gems as precious metals. But to a small band of gem and mineral dealers in Fallbrook, 50 miles to the north, the Jessop clock is more than a remembrance of times past. To them, it is a symbol of times present and the fact that they have revived, albeit on a small scale, the gem mining, lapidary and export trades for which San Diego was once world-famous.

Glory days

In the first decade of this century, the adjoining Mesa Grande and Pala districts of San Diego County some 60 miles north of the city were a gemstone cornucopia, producing, among other things, garnet, kunzite, morganite and topaz. But what prospectors were most keen on finding was tourmaline, especially the pink variety that is a regional specialty. Fortunately, the discovery of pink tourmaline in San Diego County just near the turn of the century coincided with the reign of this gem’s greatest enthusiast in recorded history: Tzu Hsi, the Dowager Empress, who ruled China from 1860 to 1908 (and then wielded behind-the-throne power until her death in 1911).

|

| China’s Dowager Empress was wild about San Diego’s tourmalines. Her love of this gem triggered the California boom in the early 1900s. (Photo courtesy Peter Bancroft) |

Known for eccentricity as much as despotism, Tzu Hsi was as wild about pink tourmaline carvings and accessories as Imelda Marcos is about shoes—so wild that wearing them became de rigueur in China’s royal circles. Writing in the January. February 1991 issue of Matrix, a newsletter devoted to mineralogical history, Charles Pearson notes that the gem “was used for carving purposes and to fashion buttons or toggles for jackets worn by the royal court and wealthy individuals.”

Sino-San Diego trade relations operated smoothly—and, it goes without saying, prosperously—because they were coordinated by a most prestigious and adept middleman: Tiffany & Co. At a lecture during GlA’s recent [1991] International Gemological Symposium in Los Angeles, miner/dealer Bill Larson, Pala International, Fallbrook, outlined how the New York firm sated China’s voracious appetite for pink tourmaline:

First, J.L. Tannenbaum, a Tiffany gemologist, would receive an order from the imperial court for a specific quantity, usually several tons, of tourmaline. Next, he would wire money deposited by the Chinese government in a special account at the Import-Export Bank of New York (later to become Chase Manhattan) to hire local ranchers and cowboys to mine what was needed When the shipment was exhausted, the court would make another order and Tannenbaum would repeat the process. At Mesa Grande alone, reports miner and historian Peter Bancroft in his book, Gem and Crystal Treasures, 120 tons of gem-grade tourmaline valued at $800,000 was mined between 1902 and 1910. The California tourmaline boom ended in 1911 with the death of the Dowager Empress. World War I marked an end to meaningful mining in the San Diego area until well into the 1970s.

|

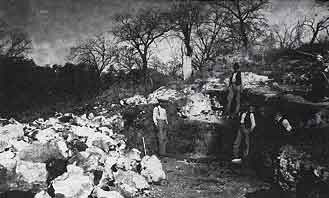

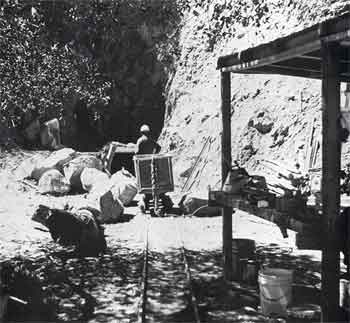

| The Himalaya Mine, California’s biggest producer of tourmaline, ca. 1900. (Photo courtesy Peter Bancroft) |

Local heroes

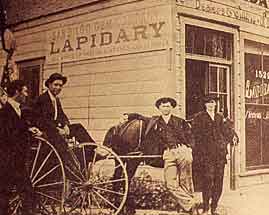

The tourmaline boom overshadowed much else of merit during San Diego’s glory days as a gem producer. Few today even know that many of the city’s jewelers capitalized on the area’s reputation as a mining center to make custom jewelry featuring local gems. There were four major lapidaries in San Diego, working rough from hundreds of claims, says Bancroft. No wonder jewelers like Joseph Jessop built reputations as purveyors of the nearby mountains’ local colors.

|

| A miner at the Pine Tree portal of the Himalaya Mine, San Diego County, California, ca. 1980. (Photo: Mike Havstad) |

Jessop, a second generation jeweler and the son of a watchmaker, may have been a miner himself. The firm maintains that he jeweled his magnificent San Diego street clock with native gems the family mined and cut. Although we can find no reference to any mine owned by Jessop in the standard reference works on U.S. mining such as Sinkankas’ Gemstones of North America, this does not rule out the possibility of Jessop involvement in local gem mining. Sinkankas believes Jessop could very well have been an investor in or the main agent for a mine or two.

Whatever the case, there was ample precedent for local jewelers acting as miners and distributors of local mine output. Another famous San Diego jeweler, John W. Ware, who moved to the city in 1910 from upstate New York, was known to have owned and operated a mine which produced, among other species, pale blue topaz. A gifted lapidary and jewelry maker, Ware so successfully marketed his small mine’s blue topaz that he was forced to import material from abroad to meet demand for the gem.

|

| Jeweler John Ware, shown in the cabin doorway, owned and oversaw a blue topaz mine on Smith Mountain. (Photo courtesy William Larson) |

Ware’s love of colored stones, California’s especially, eventually led him to join the American Gem Society in 1935 and become one of its first Certified Gemologists. When he died in 1944, Ware had a reputation as a tireless promoter of gemology and a mentor to young jewelers. That reputation is very much alive today. Miner Bill Larson, who runs a retail store called The Collector in Fallbrook, admittedly models himself in part after Ware and keeps a complete archive of Ware photographs and other memorabilia—even though Larson was born the year after Ware died.

Yet for all their knowledge of and commitment to California gems, local devotees of these stones like Jessop and Ware were overshadowed as players in the San Diego gem boom by Tiffany and Co. The firm’s prominence—better yet, dominance—in the domain of colored stones was unassailable. Indeed, by the turn of the century, George F. Kunz, then a Tiffany’s vice president and buyer, was already the godfather of gemology—so influential that when a new pink spodumene was discovered near Pala in 1902 it was named kunzite over the protests of some miners and mineralogists.

But the ultimate demonstration of Kunz’s power came a few years later with the discovery of a new pink beryl in San Diego County soon after named morganite by Kunz for tycoon J.P. Morgan. As it just so happened, Morgan was a major Tiffany’s customer and one of the main benefactors of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Indeed, the museum’s gem collection was studded with Morgan donations, many of them U.S. gem and mineral specimens originally bought from Tiffany’s at the urging of Kunz, who acted as advisor to the plutocrat. One can only be thankful that Morgan’s name was not Warbucks or today we might be stuck with warbucksite.

|

| Early California gem cutters worked rough from hundreds of claims. There were four major lapidaries in San Diego. Some local cutters also made and sold jewelry. (Photo courtesy Peter Bancroft) |

The long ebb

After the California tourmaline boom subsided, just prior to the outbreak of World War I, San Diego began to lose its grandiose reputation as, in the words of one penny stock prospectus for a gem mine, “the Kimberley of tourmaline.” The region’s reversal of fortune as a gem producer only accelerated after World War I when the world was glutted with goods from Brazil and other gem-rich countries.

However, mining in Southern California never went into full eclipse. Between 1912 and 1925, the Chinese continued tourmaline extraction operations that were so secretive, says Bancroft, “we can’t find any artifacts or other signs of their presence. It’s just common knowledge in these parts that they worked several deposits.” One Chinese jeweler was known to have shipped local tourmaline to Peking in the 1920s. Another Chinese, himself a miner, also ran a gambling parlor where losers at roulette were given pieces of tourmaline.

|

| Blue topaz and smoky quartz on albite feldspar from Little Three mine (documented by G.F. Kunz). (Photo: Tino Hammid) |

No doubt, many of these “consolation prize” tourmalines were magnificent mineral specimens that today would fetch hundreds and even thousands of dollars in the thriving collectors’ market. But before World War I and for a while thereafter, mineral collecting was still an esoteric hobby. As miner Frederick Ryerson wrote in Exploring and Mining for Gems and Gold in the West: “It was not until 1919 that fine specimens of gemstones brought more than their cutting value. Before that time there were wonderful specimens destroyed in getting the gems out of them. I was guilty of this waste along with others.”

If wide international interest had not developed in mineral specimen collecting during the 1920s and ’30s, gem mining in San Diego County might have petered out completely. But the lure of finding superb specimens such as the famous kunzite slab (see photo below) was as much a spur to prospectors as finding fine roughs. California mines excelled at giving both and this fact is the key to the survival of its gem mining tradition. Miners like Frederick Sickler, who is now credited with the discovery of San Diego kunzite, Ryerson, Herbert Hill and Ralph Potter were keepers of what at times seemed a low-burning flame. Today George Ashley, the last of a breed of men whose whole life is entirely devoted to gem mining, continues prospecting although he is in his 80s.

|

| Pink tourmaline with attached lepidolite mica from the Stuart Lithia mine. (Photo: Tino Hammid) |

The new breed

Without a doubt, credit for San Diego’s rebirth as a viable gem mining locality belongs to Potter, who, in the early 1950s, acquired the Himalaya Mine at Mesa Grande and tunneled in some 500 feet on the mine’s west side. Fortunate to find pockets filled with beautiful crystals, Potter traveled around the country selling and was able to make his mine a paying operation. Shortly afterward, Louis Spaulding began profitable mining of gorgeous orange spessartine garnet at his Little Three Mine near Ramona. “It is Potter and Spaulding who once again made gem mining a commercial venture in San Diego,” says Sinkankas.

Their success paved the way for a new generation of miner-dealers who were part of the explosion of interest in mineralogy and rockhounding in the late 1950s and ’60s. Talk to a Californian like Larson, Ed Swoboda or Bancroft who grew up as a rockhound and you invariably sense a person whose occupation is as predictably an outcome of childhood pursuits as that of a Hoosier basketball player.

Larson is clearly the fulcrum of the San Diego renaissance and a perfect embodiment of its traditions: gem miner, lapidary, custom manufacturer, importer, dealer and retailer. But he hasn’t only followed in others’ footsteps. He’s cut a path of his own, one so successful, says Sinkankas, that “he has become a magnet drawing other dealers and cutters to the area.”

|

| Bi-colored tourmaline with attached lepidolite mica from the Himalaya mine. (Photo: Tino Hammid) |

A 1966 graduate of the Colorado School of Mines with a degree in geological engineering, Larson is equally at home in the gem and mineral worlds. For him, there is no separation between the two, although he recognizes a Great Divide between them in the minds of most jewelers and rockhounds. That’s a division he would like to see end because he feels there is no basis for it. “As a miner I’m as much on the lookout for fine specimens as fine rough crystals,” he explains. “Both are miracles of nature.”

This isn’t just rhetoric. Walk into either of Larson’s two retail stores one in Fallbrook and the other in La Jolla [now Carlsbad], and you’ll see an impressive intermingling of fine cut stones and mineral specimens. Owner of perhaps the finest private gem and mineral collection in America, Larson is as fond of showing guests stunning specimens as faceted gems—and equally conversant about both. The unity between the gem and mineral realms exists in every phase of his business. Maybe that’s because ’s been a miner as long as he’s been a dealer.

Larson entered the gem mining field in 1968 when, along with fellow dealer Swoboda, he formed Pala Properties International and leased three San Diego mines, the Stewart Lithia, Tourmaline Queen and Pala Chief. Of the trio, the Queen produced the most memorable material. Indeed, one strike made in January 1972 at this mine uncovered what Larson calls “the pocket of the century,” brimming with magnificent rubellite crystals, some with crystals of peach-colored morganite attached to them, that remain among the most unusual and valuable mineral specimens ever found. “That find put us on the map,” Larson says.

|

| Famous author and gemologist, G.F. Kunz of Tiffany Co. examines the pink spodumene slice that was later named kunzite in his honor. |

In 1978, Larson, then on his own, bought out a nine-man syndicate formed by Potter that owned the greatest of all San Diego’s tourmaline mines—the Himalaya—and immediately began to extend old tunnels. In the 13 years since, Pala International has dug 7,000 feet of tunnel at the Himalaya, extracted around 3 tons of gem material (90% of it suitable for beads or carving, 19% for cabochons and only 1% for faceting) and spent, on average, around $300,000 to $400,000 per year on the feast-or-famine venture. “From a pure ledger standpoint, we’re just breaking even,” Larson says. “But if you factor in all the publicity the Himalaya has received, it has been highly profitable for us.” Of course, it helps that in May 1989 and April of this year, the mine’s chief of operations, John McLean, hit two major pockets filled with gem and mineral crystals. But in between it was slim pickings.

|

| This famous slab of kunzite (with a faceted stone below) became an inspiration to California prospectors. It now resides in the William F. Larson collection. (Photo: Tino Hammid) |

Away from it all

The trip from Larson’s store in Fallbrook to his mine in Mesa Grande takes roughly an hour by car—preferably one with four-wheel drive for the mine’s steep, rocky access road. Unlike his predecessors, John Ware and Joseph Jessop, Larson does not feel the need to run his retail store in downtown San Diego. Instead, he chooses to base himself on the outskirts of the small, sleepy town of Fallbrook in a spot one needs directions to find. From the outside, in fact, his store could be mistaken for a stylish ranch home and passed right by. Inside it’s more like a small museum meant to heighten gem awareness and appreciation for the shoppers who make the trek there—obviously predisposed to buy something.

Consumers aren’t the shop’s only visitors. During an April [1991] visit there, this reporter met a mineral dealer from Italy as well as a buyer from Tiffany’s. Faxes indicated upcoming visits from German, Brazilian and Hong Kong dealers who come as much to buy as to sell.

Fallbrook’s proximity to San Diego County’s gem mines makes the town an important stopover for dealers from all over the world. “Just before the Tucson show in February hundreds of dealers from Europe and Asia visit here,” says Tony Jones, California Rock and Gem, a Fallbrook resident for the past 20 years. Because it is such a draw for the international gem trade, some of the six or so local dealers like to think of their town as a kind of Idar Oberstein in miniature.

Jones, a mineralogical adventurer who has mined diamonds in the jungles of Venezuela, thinks his fellow dealers are drawn to Fallbrook by factors like climate and camaraderie. But he doesn’t deny that to most dealers Fallbrook will seem in the middle of nowhere. Nevertheless, Jones quickly counters that the town’s isolation has more advantages than disadvantages.

|

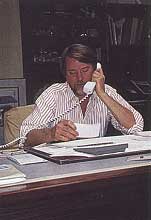

| William Larson, founder and owner of Pala International /The Collector, ca. 1991. |

Most of those advantages have to do with lifestyle. For the nine months of the year he’s not traveling from city to city on the gem and mineral show circuit, Jones operates a large mail-order business out of his house. Electric guitars, conga drums and sheet music in his double-duty office and den suggest an unrepentant 1960s approach to personal living where rocks and rock music share equal love – if not time. The freedom to be one’s self at any, possibly every, moment seems as important to most of Fallbrook’s handful of other dealers, nearly all of whom cater to rockhounds and collectors.

But with boundaries between the retail jeweler and hobbyist worlds rapidly blurring, Fallbrook’s horizons seem to be expanding. Several lapidaries now live in the area. One of them, Meg Berry, who works for Pala International, recently won three of the 23 prizes— two firsts and a second—in the first Cutting Edge lapidary competition sponsored by the American Gem Trade Association.

Next, Fallbrook may become as much a gemstone treatment as a cutting and distribution center. A new local venture, Beta Color Inc., will offer, among other services, irradiation of gems using linear accelerators and, in time, other forms of irradiation, plus heat treatment. Supervised by nuclear engineer Doug Parsons, this gem enhancement facility could become one of the most advanced in the world. “Think of it,” Larson says, “you buy topaz rough in Sri Lanka, have it cut in China, then treated in California. When it comes to gem knowledge and technology, this will put Fallbrook right in the center of things.”

|

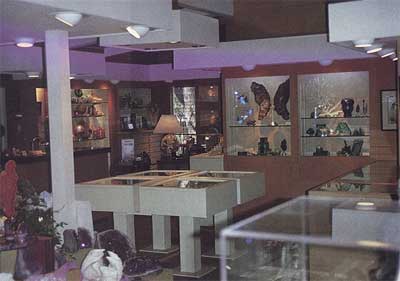

| The Collector, located amidst a live oak forest in beautiful Fallbrook, California. |

|

| Interior of The Collector, showing the various gems, mineral specimens, jewelry and objets d’art offered for sale. |

|

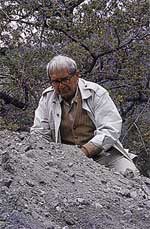

| Noted gemologist and author, John Sinkankas, examines tailings from the Himalaya Mine for tourmaline specimens. |

![]()

For further information on mining, see also: