Buying

and Selling Gems:

What Light is Best?

Part I: Natural Light

By William

J. Sersen, Ph.D., AG (AIGS) and Corrine Hopkins, FGA,

AG (AIGS)

Formerly of the Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences,

Bangkok, Thailand

Note: This article is reprinted with permission. It originally appeared in the Gemological Digest, Vol. 2, No. 4, 1989, pp. 13–23. To read Part II of this article, click here

|

Abstract:

Natural light has

traditionally been considered the standard light source

for buying and selling gems. But is it really a standard?

In Part I of this two-part article, dealers of various nationalities

were asked to describe their experiences with natural light

as it relates to rubies and blue sapphires. Their responses

produced a host of surprises, not the least of which was

that few dealers agreed as to just how natural light affects

a stone’s appearance.

This prompted AIGS to do its own

study on selected rubies and blue sapphires. Results of

both the dealer poll and the AIGS study appear here. More

importantly, the variations of natural light are accurately

cataloged, with tables provided that will allow dealers

in many places around the world to determine what type of

natural light is best suited to their buying and selling.

Part II of this article will appear

in a future issue, and will discuss the suitability and

use of artificial light sources.

Introduction

In the business of buying

and selling precious stones there are a number of little

tricks picked up along the way, tricks that often make the

difference between profit and loss. Collectively, we might

call them “experience,” for that is normally how

they are acquired and the price is, usually, high. “Experience”

of this sort is not found in gemological texts; it comes

only through hard knocks—i.e., buying stones from

someone who has a bigger box of experience than your own—or, via a bit of friendly advice passed on by one

who has been there before. Most dealers have a collection

of this “experience,” kept in a box at the back

of the safe or in some dusty drawer. It amounts to the small

pile of gems which are unsalable; the gems you have learned

valuable lessons by buying. In other words, gems you should

not have bought in the first place.

One bit of experience that every

stone dealer worth his rocks soon acquires is that a stone’s

appearance is not constant. Instead, it can and often does

change with the quality of light under which it is viewed.

And a change in color appearance often means a change in

value.

In the days before electric light

sources, traders could only view their prospective purchases

under natural light or by the light of a candle. Natural

light means direct sunlight and skylight (light coming from

all directions of the sky except directly from the sun).

Some dealers would examine a stone

at various times of the day, realizing that the position

of the sun in the sky, together with weather conditions,

affected overall color appearance; others took it one step

further, viewing the gem in sunlight, skylight and in the

shade of a tree in order to get an idea of how it would

look in any lighting situation. Similar practices continue

to this day, despite the availability of artificial lights

of various kinds.

So, why examine gems under natural

light, the quality of which is subject to a myriad of changing

weather conditions, when our Modern Age offers us incandescent

and fluorescent (including simulated daylight) lighting?

For that matter, why bother to view a gem under more than

one light source, be it natural outdoor light at a given

time(s) of the day vs. the stone’s appearance in the

shade, or in fluorescent simulated daylight vs. incandescent

lighting? The answers to those questions lie in whether

you are an astute buyer or seller, and in what part of the

world you happen to be conducting business.

“One bit of experience that every stone dealer worth his rocks soon acquires is that a stone’s appearance is not constant. Instead, it can and often does change with the quality of light under which it is viewed. And a change in color appearance often means a change in value.”

Viewing gems under natural light

As in other parts of the world, it is common practice in

Thailand for dealers and professional buyers to view colored

stones at a table situated at a window. Natural light is

the accepted lighting “standard,” some dealers

and buyers preferring north skylight only.

In the days before the GIA

Diamondlite, such was also the case internationally with

the color grading of diamonds.

Writing in 1916, Frank B.

Wade notes in his classic volume on diamonds:

What Mr. Wade has to say about north light and (especially) weather conditions is echoed by many local colored-stone traders today. However, the authors of this article were particularly struck by the comment “between 10 A.M. and 2 P.M.” as it is reminiscent of remarks heard in Thailand and Burma about rubies and blue sapphires looking “better” or “worse” at different times of day.In the first place see that you have a good north light, unobstructed by buildings or other objects. There must not be any coloured surface near by to reflect tinted light, as a false estimate might easily result.“In the second place, do not attempt to judge stones at all closely except in the middle of the day, say between 10 A.M. and 2 P.M. Very erroneous results may easily be had by neglecting this precaution.“Dark or dull days should be avoided also. One must have plenty of good neutral light to make fine comparisons.

|

So,

wondered the authors, does the quality of natural light

vary enough to cause noticeable differences in the appearance

of rubies and blue sapphires at different times? Not only

had Bangkok dealers mentioned this before, but some had

gone so far as to say that they regulate their buying and

selling according to the time of day and weather conditions.

It was decided to telephone

a few local colored-stone dealers, all of whom have been

in the trade for years, and ask them the following questions:

Do rubies and/or blue sapphires change appearance at different times of the day? If yes, when do rubies look better/worse? When do blue sapphires look better/worse?

All

agreed that the color appearance of rubies and blue sapphires

changes in the course of a day, and all specified what times

those stones look best/worst. But, to the authors’ astonishment,

there was no consensus as to what those times are. This was

all the more interesting in that a few stated that they try

to coordinate their buying/ selling of these stones with the

time of day in which the color appearance was best (= selling)

or worst (= buying).

Spurred on by curiosity, the

authors and two other AIGS staff carried out their own experiments.

A selection of rubies and blue sapphires of mixed “type

categories” (see Sersen, 1988) was periodically examined

for two weeks. North and east window lighting was used. Weather

conditions during this period ranged from bright and sunny

to dark and rainy. The purpose of these experiments was, of

course, to see if the stones would change at all in color

appearance.

|

The

gems were viewed four times daily. Hue, lightness and saturation

was recorded on each occasion, together with respective

weather conditions. These notations were based strictly

on visual observation. No conclusive results were had, possibly

because no comparison reference was used; only the testers’

memories were involved, just like with most dealers.

Now more curious than ever,

the authors took a formal written survey of 20 colored-stone

traders in order to compare their answers and see what patterns,

if any, might emerge.

The questions asked concerned

the lighting conditions used for buying and selling, whether

rubies/blue sapphires change color appearance at different

times of the day (and if so, when do they look best/worst)

and specifically what factors are thought responsible for

color appearance changes when such changes are seen.

All 20 traders were interviewed

in Bangkok. They consisted of 9 Thais, 6 Americans, 3 Burmese,

1 Canadian and 1 Malaysian. The majority are local wholesalers

and sales personnel for local wholesalers. The others consist

of Thailand-based brokers and overseas-based dealers who

buy in Thailand and/or Sri Lanka and sell in Europe and/or

America. The trade experience of those questioned ranged

from 2 to 50 years, with most having at least 10 years experience.

Every attempt was made not to phrase questions in a leading

way. People were simply asked questions and encouraged to

“talk on” for as long as they wanted, without

prejudicing comments from the interviewer.

“All agreed that the color appearance of rubies and blue sapphires changes in the course of a day, and all specified what times those stones look best/worst. But, to the authors’ astonishment, there was no consensus as to what those times are.”

Survey results

What lighting do you

use when buying stones?

Most people (75%) said they buy ruby and sapphire

after examining those stones under natural skylight only.

Of those, seven people prefer north or northwest skylight,

seven use any direction of skylight, one specified north

or south skylight and one south skylight only. Of the remaining

20%, one buys only after viewing each stone under north

skylight and direct sunlight; one uses north skylight or

a “daylight lamp”; two view their prospective

purchases under multiple natural and artificial lighting

conditions; one said he buys using “whatever lighting

arrangement happens to be available.”

Lighting used when selling stones?

The majority (55%) of those questioned said they

use skylight for selling as well as buying. Several stated

categorically that the color appearance of rubies and sapphires

changes with the time of day and they therefore prefer to

buy in “bad light” and sell in “good light.”

The rational behind this is that if the stone appears reasonably

nice under less complimentary lighting, it will look good

under any (natural) lighting. Selling in “good light”

means exactly what it implies: during times when natural

lighting conditions make the gem look best.

One dealer said he buys in

Sri Lanka using only northwest skylight, and sells in his

U.S. office under quartz halogen lighting. Another stated

she buys rubies under north skylight, but prefers selling

them under “direct sunlight in the afternoon, because

the light is yellow.” In both instances, the lighting

used for selling is perceived as complimentary to the gem’s

color appearance.

The rest largely buy in skylight

and sell in whatever lighting is available or under lighting

conditions expressly requested by a customer, such as skylight

from a particular window direction. Obviously, dealers who

do all their buying and selling from one office location

have more control over lighting conditions than does a broker

who must sell—and accept consignments—under

whatever lighting is available, natural or artificial.

|

Do rubies and/or blue sapphires change

appearance at different times of the day?

This question solicited

the most interesting answers. Ninety-five percent of those

polled replied with a firm “Yes.” Thirteen said

rubies tend to look best only at certain times of the day.

Seven said the same for blue sapphires. Conversely, nine

people remarked that rubies often appear less beautiful

at definite times of the day, with 11 saying the same of

the sapphires.

Though many had firm opinions on

this matter, there was little agreement on what times these

stones look better or worse! For example, some said rubies

and blue sapphires look the best at specific times of the

morning, though others said mid- or late afternoon. Two

dealers noted that rubies in particular look best towards

sunrise and sunset.

Those who did not cite specific

times when these stones look “better” or “worse”

often associated apparent color appearance changes with

weather conditions. For instance, five people observed that

blue sapphires look best “at any time the sky is clear.”

Two said the same of ruby. However, a third stated emphatically

that rubies look best “only when the sky is slightly

cloudy, because clear blue skies give them a purplish tint.”

“Though many had firm opinions on this matter, there was little agreement on what times these stones look better or worse! For example, some said rubies and blue sapphires look the best at specific times of the morning, though others said mid- or late afternoon. Two dealers noted that rubies in particular look best towards sunrise and sunset.”

And, yes, several people volunteered that they prefer buying and selling ruby and/or sapphire in strict accordance with the times and/or weather conditions they cited.

Why do these changes in color appearance

occur?

Some said they did not know. Others ascribed the changes

to weather conditions or the “quality of sunlight”

at different times of the day. A few said it all depends on

the relative position of the sun in the sky-and the corresponding

light intensity.

When asked specifically if

light intensity affects the beauty of a ruby and/or blue sapphire,

95% said “Yes.” Six dealers added that light blue

sapphires look best under dimmer lighting (‘toward the

evening or whenever the sky is cloudy’). Dark sapphires

and rubies, said several, look best when the light is comparatively

bright (‘around midday or noon’).

A few said that inclusions

are more visible in lighter rubies or sapphires when those

stones are viewed under intense natural light. As one wholesaler

put it, “their nakedness is exposed.” 1

It was evident when talking

to those surveyed that if lighting conditions are not optimum—for instance, the presence of a dark cloudy sky—many will not show stones to buyers. In the Bangkok gem trade,

the general rule for natural light is “the brighter the

better.” This is partly why dealers here prefer natural

over artificial light; that is, natural light is more intense

than that of an “artificial diffused daylight source.”

Hence, it is often more complimentary to stones.2

Viewing gems under natural light in

different countries

The following story is probably familiar to many of you:

So-and-so bought a blue sapphire in Bangkok or Sri Lanka. He brought it home to America, where it seemed to “look different.” So-and-so thought to himself, “Is this the same stone? It doesn’t look as nice as it did when I bought it. Did those Asian dealers switch the stone on me? Maybe they did, because it looks different!”

This

is a common story. The authors have heard it from a number

of people (including local dealers and overseas buyers) over

the years. This story arises because stones can and do assume

slightly different color appearances in different latitudes.

As we shall see, this is partly ascribable to regional variations

in atmospheric moisture, dust and pollutants affecting the

color quality of the light.

To quote an example given by

one local dealer, “any ruby or blue sapphire that looks

dark in Thailand will look darker in Europe or America.”

Another dealer (an American

who frequents Bangkok, not included in the survey above) had

once mailed stones to customers first in Los Angeles, California,

and thereafter Montana. Reactions he received–concerning

the same stones—indicated that those stones appeared

differently to each party under natural light. This may come

as no surprise to anyone who has seen the skies of pollution-choked

Los Angeles vs. the clear blue Montana skylight.

Benjamin Zucker (1976) has

pertinent comments on this same subject:

One of the gem dealer’s distinctive talents must be to add or subtract in his mind portions of the color and brilliance that he sees, so he can make allowances for being in Amsterdam, in India, or inside a New York retail establishment with incandescent lighting.“A June afternoon in Bombay… will emit a light so overpoweringly bright that the ruby will take on a magnificent deep red color with a vibrant cast of brilliance.… If the same stone is shipped to New York and examined in natural New York daylight, it will appear a considerably darker shade of red and less brilliant. This is due to the high amount of pollution over New York and to the fact that New York lies farther from the equator than Bombay. But Amsterdam light is even grayer than New York daylight!

|

A scientific basis?

So, why do gems appear different

under natural light depending on the latitude, weather conditions,

and time of the day? For that matter, do they appreciably

change in appearance, or is this largely a product of imagination?

Though imagination and the

fallibility of one’s color memory probably play a role,

there is ample scientific support for general claims of

color appearance change. In order to appreciate this point,

we must first define skylight, sunlight and their relationship

to the principles of color temperature and the scattering

of light.

Skylight, or, why is the sky blue?

As mentioned before, skylight

is the light we perceive when looking away from the sun

at the sky. Sunlight is the light observed when looking

directly at the sun. Daylight may be thought of as a combination

of skylight and sunlight.

Sunlight and skylight differ

in appearance. On a clear day when the sun is overhead,

sunlight appears whitish. As the afternoon progresses, it

becomes increasingly yellow, then, depending on atmospheric

conditions, orange, and finally, just before sunset, red.

This shift in color is described in terms of color temperature,

which is measured on the Kelvin scale. Thus, the color temperature

of sunlight at sunrise or sunset is about 1,800° Kelvin,

signifying the predomination of red wavelengths. Temperatures

of 5000° K to 5500° K denote a more even distribution

of all wavelengths, resulting in the whitish appearance

the sun assumes at noon.

Skylight ranges from very

pale blue to deep blue. The purity and saturation of the

blue is influenced by atmospheric moisture, dust and pollution.

Generally speaking, the sky is palest when the atmosphere

is humid or laden with dust (Figures 3 and 10); it is deepest

blue when the air is dry and free of pollutants (Figures

1 and 2). This corresponds to color temperatures of about

6500° K to well over 20,000° K, respectively, the

higher Kelvin temperatures indicating predomination of the

blue-violet wavelengths.

The color quality of the

sky varies with latitude, partly because different latitudes

have correspondingly different weather patterns. Countries

with drier air tend to have deeper blue skies; those with

more atmospheric moisture tend to have paler skies (Mueller

& Rudolph, 1972).

|

Therefore,

the quality of skylight at any given latitude depends on

a complex interaction of sunlight with the local presence

of atmospheric moisture, dust and pollutants.

Specifically, it is the scattering

of light that causes the blue color of the sky and the shifts

in color temperature of the skylight and direct sunlight.

The word scatter literally

means “to cause to separate widely.” In this context

small particles of matter, such as air molecules and dust,

cause the individual photons of impinging sunlight beams

to deflect (scatter) in all directions. As sunlight enters

the earth’s atmosphere, violet and blue wavelengths

are scattered the most, followed by green, yellow, orange

and red, in that order. Shorter wavelengths (violet, blue)

are scattered about ten times more so than the longer red

wavelengths (White, 1959).

To visualize this phenomenon,

imagine a ray of white light (the composite of all spectral

hues) passing through a cloud of smoke. The blue portion

scatters off in all directions. With much of the blue light

eliminated, the beam appears more yellow as it exits the

cloud. An observer (Observer A in Figure 5) looking directly

at the beam as it leaves the cloud will notice that it has

a yellowish color. Someone viewing the cloud from any other

direction will see scattered bluish light (Observer B in

Figure 5).

Similarly, if our observer

looks directly at the sun, he perceives it as one color

(whitish, yellow, orange or red, relative to atmospheric

conditions and the sun’s position in the sky), though

the sky itself appears blue because of the scattering effect

(Figure 6). When the sun is overhead and the weather is

clear, the entire sky appears light blue. This is the composite

color blend of the scattered wavelengths, the additive mixture

of violet, blue, green and yellow.

As the sun continues on its

westward path, increased scattering takes place till, shortly

before sundown, most of the blue and violet wavelengths

are “scattered out.” Hence, a stationary observer

watching the sky from noon till late afternoon may observe

a gradual increase in the saturation of the blue sky: to

wit, an increase in color temperature which can potentially

span many hundreds, and even thousands of degrees Kelvin.

This is not readily observable when the sky is overcast,

laden with dust or strongly polluted.

“Specifically, it is the scattering of light that causes the blue color of the sky and the shifts in color temperature of the skylight and direct sunlight.”

|

|

The Purkinje shift

One day, many years ago, a man named Johannes von Purkinje

went walking in the fields at dawn. He observed that blue

flowers looked brighter than red flowers. Later that day,

when the sun was overhead, the red flowers looked brighter

than the blue ones. Conclusion? The human eye is more sensitive

to blue when the light is dim and red when the light is

strong. This phenomenon is called the Purkinje shift. Because

of it, flowers that are bright red on a sunny afternoon

look bluish-red toward evening (Varley, 1980).

The eye’s perception

of visible light under varying light intensities is illustrated

by the spectral sensitivity curve below. Note the shift

in sensitivity toward the blue-violet end of the spectrum

when lighting is dim.

|

The bottom line

Now that we have most of the science out of the way we can

get down to the million dollar question. Just how does all

this affect the color appearance of rubies and blue sapphires?

In a nutshell, blue sapphires may tend to “look better”

in the late afternoon or early morning when viewed under

skylight. With increased scattering of shorter wavelengths

during those periods, the skylight itself is more blue.

The effect on the stone is comparable to that of shining

a blue light on a white egg: the egg appears blue. Additionally,

the eye is more sensitive to blue during these same periods

because of the Purkinje shift.

Rubies could also appear

more saturate in the late afternoon or early morning, but

only if viewed under direct sunlight, the longer (i.e.,

redder) wavelengths then dominating that light. This is

summarized in tables 1 and 2.

|

| Table 1: Relative color appearance of sunlight and skylight at different times of day | ||

| Time | Direct Sunlight | Skylight |

| Sunrise (06:00–08:00) | Very yellowish to red | Very blue |

| Mid-Morning (08:00–11:00) | Less yellowish | Less blue |

| Mid-Day (11:00–13:00) | Least yellowish | Least blue |

| Mid-Afternoon (13:00–16:00) | Less yellowish | Less blue |

| Sunset (16:00–18:00) | Very yellowish to red | Very blue |

| Table 2: Relative color appearance of rubies/blue sapphires under varied natural lighting conditions and times | ||||

| Time | Ruby | Blue Sapphire | ||

| Direct sunlight | Skylight | Direct sunlight | Skylight | |

| Sunrise (06:00–08:00) |

Most saturate red | Least saturate red | Least saturate blue | Most saturate blue |

| Mid-Morning (08:00–11:00) |

Moderate saturation red | Moderate saturation red | Moderate saturation blue | Moderate saturation blue |

| Mid-Day (11:00–13:00) |

Least saturate red | Most saturate red | Most saturate blue | Least saturate blue |

| Mid-Afternoon (13:00–16:00) |

Moderate saturation red | Moderate saturation red | Moderate saturation blue | Moderate saturation blue |

| Sunset (16:00–18:00) |

Most saturate red | Least saturate red | Least saturate blue | Most saturate blue |

Why use north skylight in particular?

It is often heard that north skylight is the best natural

light to use for examining gems. As a Singapore diamond

dealer recently told the authors: “Diamond dealers

from Singapore to Europe who don’t have a GIA Diamondlite

handy, examine stones under natural north light. This is

common practice.” Many colored-stone dealers also prefer

using north skylight.

Besides Wade’s reference

to north light, others mention it in the literature. A former

employee of the Burma Ruby Mines Company (Keely, 1982) tells

the story of a Burmese ruby transaction, in which he relates:

When discussing the color grading of pearls, another person (Anonymous, 1982) observes:“…The next day, U So arrives at U Pu’s house about 2:45 p.m. and is taken by U Pu to a long room containing a large window facing north. U So takes the proffered ruby in the rough and walks to the window, where he examines it most carefully in the purest northern light which is said to be available at 3 p.m.…”

“As well as the lustre of the pearl the dealer also looks for the colour. This is best assessed when the pearl is placed on a sheet of completely white paper and examined by north light…”

![]() Typical

of written accounts and statements such as these, nobody

ever explains why north skylight is preferred. What is the

reason?

Typical

of written accounts and statements such as these, nobody

ever explains why north skylight is preferred. What is the

reason?

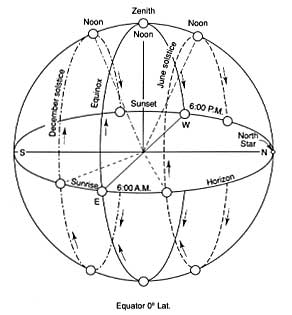

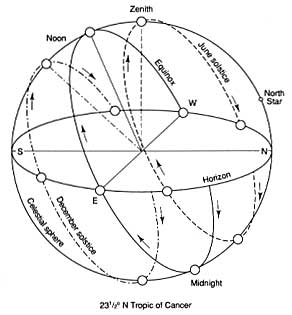

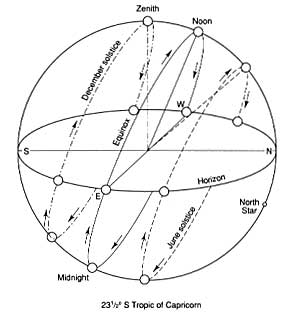

![]() Within

latitudes north of the equator, the sun passes over the

horizon thru a southerly portion of the sky with respect

to an earthly observer. This is especially the case at the

higher latitudes, such as New York City (41°N) or Amsterdam

(52°22N), where the sun is never directly overhead

(at zenith) at any time of the year. Practically, this means

that at those latitudes the southern sky contains more In

short, if you are looking at stones under skylight and are

in San Francisco, New York, London, Amsterdam, Antwerp—or any other major gemstone center well north of the equator—then northern skylight is generally preferred. If

you are south of the equator (Brisbane, Santiago, etc.),

southern skylight is the general rule. For those actually

on the equator (viz., Nairobi), the “best” skylight

viewing conditions fluctuate much with the season of the

year.

Within

latitudes north of the equator, the sun passes over the

horizon thru a southerly portion of the sky with respect

to an earthly observer. This is especially the case at the

higher latitudes, such as New York City (41°N) or Amsterdam

(52°22N), where the sun is never directly overhead

(at zenith) at any time of the year. Practically, this means

that at those latitudes the southern sky contains more In

short, if you are looking at stones under skylight and are

in San Francisco, New York, London, Amsterdam, Antwerp—or any other major gemstone center well north of the equator—then northern skylight is generally preferred. If

you are south of the equator (Brisbane, Santiago, etc.),

southern skylight is the general rule. For those actually

on the equator (viz., Nairobi), the “best” skylight

viewing conditions fluctuate much with the season of the

year.

This data is summarized in

Table 3. Note that this table serves as a guideline only.

For some latitudes at certain seasons (i.e., New York City

during the June solstice), the preferred skylight direction

literally changes with the time of day. For New York in

June, south skylight contains less glare near sunrise and

sunset, while north skylight is preferred most of the rest

of the day.

| Table 3: Guidelines on when and where to use north vs. south skylight | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other applicable cities: Peshawar (34°01 N), Los Angeles (34°03N) Tokyo (35°42N), Athens (37°58N), Beijing (39°55N), Madrid (40°24N), Paris (48°52N), Idar-Oberstein (49°42N), Antwerp (51°13N), London (51°30N), Amsterdam (52°22N), Moscow (55°45N) Key: “S”= south skylight, “N”= north skylight, “NS” = north or south skylight |

|

|

|

|

| Figure 11. Paths of the sun at different points on the earth at different times of year (after Strahler). | |

Conclusions to Part I, or, why use

natural light at all?

Indeed, why use natural

light? This is a reasonable question to ask. As we have

seen, the color quality of natural light—be it northern

skylight or otherwise—is affected by the position

of the sun in the sky at a given season (in turn a function

of latitude), the path-length of sunlight thru the atmosphere

in its relationship to the “scattering” phenomenon,

weather conditions and the extent to which dust or manmade

pollution permeate the atmosphere. Those are a lot of variables!

If one is making critical judgments involving potentially

large amounts of money, would it not be better to view gems

under one standard type of artificial lighting? This way

they would always look the same to everyone, at any latitude,

under any weather and/or pollution conditions, at any time

of the year.

Yes, but which particular

artificial light source would we deem standard? Incandescent?

Fluorescent? If the latter, then what kind of fluorescent

lighting? A so-called warm white fluorescent light? Cool

white? Artificial “daylight?”

For any one individual, it

would not matter which of these sources were used, as long

as that person used the same one consistently. For most

people, though, that is not the practical answer. Gem traders

often leave their offices to make purchases (there are exceptions!)

and can not be expected to pack around their favorite light

source wherever they go. Hence, a universal lighting standard

is needed in the gem trade as a whole, so that one gemstone

always has the same color appearance to everybody, everywhere,

anytime.

But again, which artificial

light best qualifies as that standard? And should there

be more than one standard: one for dealers and perhaps another

for retail outlets where lighting is more often used to

exaggerate color appearance? These and other questions are

addressed in Part II of

this article.[See Part II in next issue: Artificial Lighting:

The Options Available]

References

As regards the water of the stones, it is to be remarked that instead of, as in Europe, employing daylight or the examination of stones in the rough, and so carefully judging their water and any flaws which they may contain, the Indians do this at night; and they place in a hole which they excavate in a wall, one foot square, a lamp with a large wick, by the light of which they judge of the water and the cleanness of the stone, as they hold it between their fingers. The water which they term ‘celestial’ is the worst of all, and it is impossible to ascertain whether it is present while the stone is in the rough. But though it may not be apparent on the mill, the never-failing test for correctly ascertaining the water is afforded by taking the stone under a leafy tree, and in the green shadow one can easily detect if it is blue. (back to text)

2.

One of the authors (WJS) once saw a dealer inspecting a

blue sapphire at a Bangkok wholesale establishment. While

sitting at a long table perpendicular to an east window,

the dealer viewed that gem from a seat nearest the window.

Suddenly, he moved three seats down from the window (about

2 meters), re-examined the stone, and declared “This

sapphire has just dropped $200 in price!”

The point of this story is,

of course, that the intensity of natural light can vary

tremendously under such viewing conditions. And conditions

like these are typical when buying stones at wholesale level

in many parts of the world.

You can appreciate this more

fully by conducting a simple experiment of your own. Use

a hand-held (photographic) light meter to measure light

intensity, first from a position immediately next to a window

(which may face any direction), then at positions in half-meter

increments away from that window. It does not matter if

the sky is clear or overcast. In either instance, large

drops in recorded light intensity will occur. (back

to text)